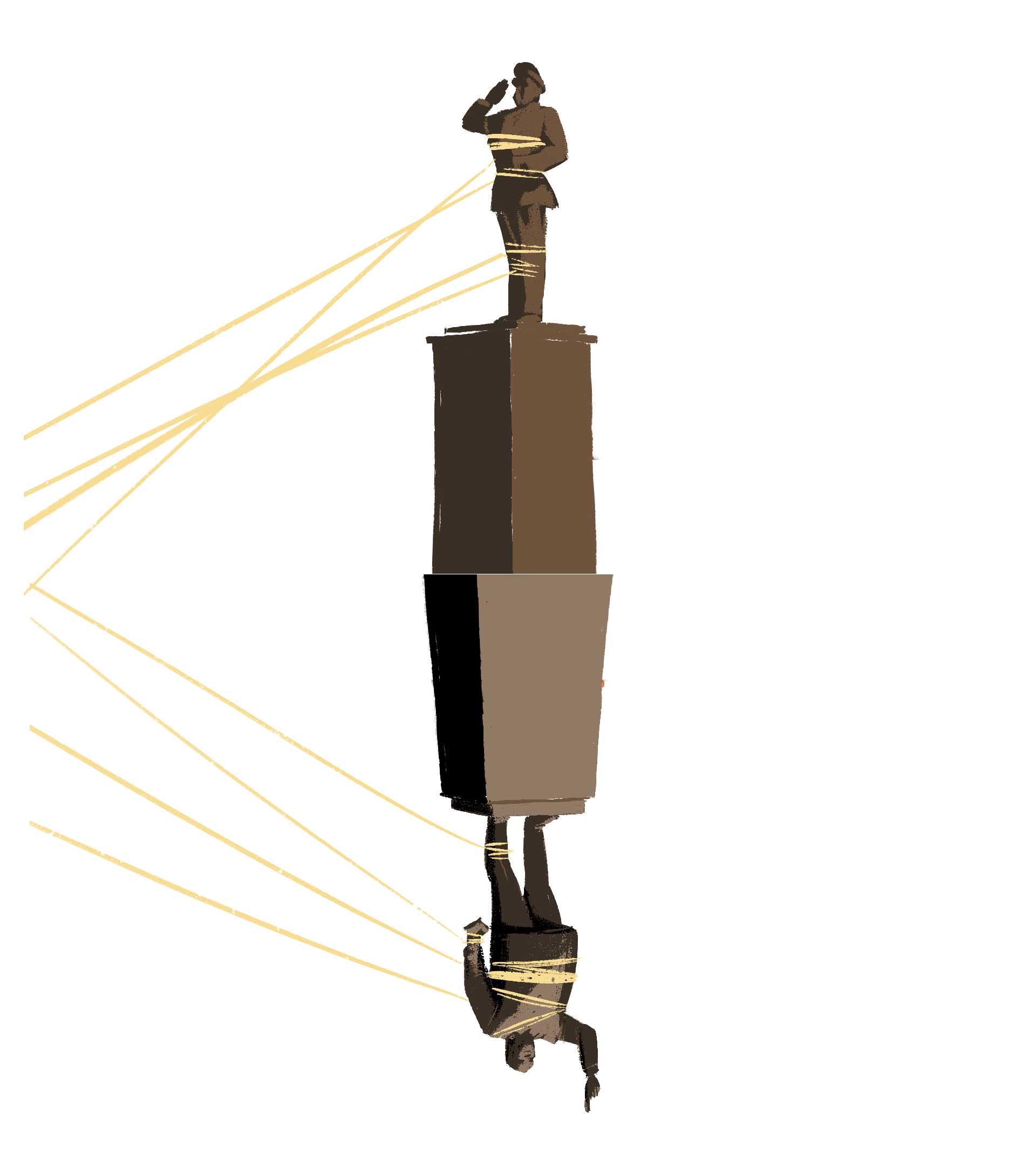

What is a coup?

According to this definition, the target of a coup must be a sitting executive, and the perpetrators must have formal ties to the national government. Movements that attempt to overthrow an entire government and which are led by those not connected to power, such as rebellions or mass protests, are not included.

While some definitions of coups limit the perpetrators to only military figures, Powell and Thyne said doing so would likely bias the data toward successful coups.

“The initial instigation of a coup attempt frequently involves civilian members of the government alone, with the military playing a later role in deciding whether the putsch will be successful,” the researchers wrote. They cite the example of a 1962 coup attempt led by Senegalese Prime Minister Mamadou Dia that failed because he was unable to gain the military’s support.

Coup perpetrators must also be “within the state apparatus,” which excludes takeovers largely directed by foreign governments. Powell and Thyne cite the example of the fall of Ugandan President Idi Amin in 1979 at the hands of the Tanzanian military, saying the action “does not constitute a coup because foreign powers were the primary actors.”

Countries with the most coups

Sudan tops the list as the African country with the most coups — attempted and successful — since 1950, with 17,

Powell and Thyne’s data show. Of those takeover efforts, six were successful, including the most recent one in October. While Burkina Faso has had fewer total coups attempts in the same period, it has the highest number of successful coups, with eight, including January’s coup. In addition to the most recent putsch, coups were successfully carried out in Burkina Faso in 1966, 1974, 1980, 1982, 1983, 1987 and 2014. A coup was also attempted in 2015.

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, had a long history of coups following independence in 1960, with eight coup attempts — six of them successful. Since 1999, the country has transferred power through democratic elections and helped usher in an era of greater stability in West Africa and the continent as a whole.

Coups per country since 1950

Sudan 17 Total attempts 6 Successful Burundi 11 5 Ghana 10 5 Sierra Leone 10 5 Burkina Faso 9 8 Comoros 9 4 Benin 8 6 Nigeria 8 6 Mali 8 5 Guinea-Bissau 8 4 Togo 7 3 Rep. of Congo 7 2 Niger 7 4 Chad 7 2 Mauritania 7 5 Guinea 6 3 Ethiopia 5 2 CAR 5 3 Uganda 5 3 Egypt 4 4 DRC 4 2 Algeria 4 2 Madagascar 4 1 Liberia 4 1 Lesotho 4 3 Ivory Coast 4 1 Somalia 3 1 Libya 3 1 Zambia 3 The Gambia 3 1 Gabon 2 Eq. Guinea 2 1 Morocco 2 Rwanda 2 2 São Tomé 2 1 Senegal 1 Mozambique 1 Angola 1 Seychelles 1 1 Kenya 1 Eswatini 1 1 Cameroon 1 Tunisia 1 1 Djibouti 1 Zimbabwe 1 1

What factors lead to coups?

The African Union Peace and Security Council

said in 2014 that unconstitutional changes of government often originate from “deficiencies in governance” along with “greed, selfishness, mismanagement of diversity, mismanagement of opportunity, marginalization, abuse of human rights, refusal to accept electoral defeat, manipulation of constitution[s], as well as unconstitutional review of constitution[s] to serve narrow interests and corruption.”

U.S. researchers Aaron Belkin and Evan Schofer have found that the strength of a country’s civil society, the legitimacy conferred on a government by its population, and a nation’s coup history are

strong predictors of coups.

Powell told VOA that a recent coup can “signal a breakdown of politics-as-usual, a change in power dynamics that prompts future counter-coups” as a result of rivalries within the army. He said that some countries fall into what is known as a “coup trap” in which a large number of coups can occur in quick succession. An example is

Mali, where four coup attempts took place in the past decade after the country did not experience any in the prior 20 years.

Mali’s 2020 coup leader Assimi Goita cited widespread popular dissatisfaction toward those in power when he seized control. However, when he carried out a coup less than a year later in May 2021, overthrowing a transitional government that he helped set up, he cited a Cabinet reshuffle that excluded two key military leaders. Goita claimed the move violated the terms of the new government. French President Emmaneul Macron called the action “a coup within a coup.”

Coup success rate

Powell and Thyne’s research shows that coup attempts in the past decade have had a far higher success rate than those of previous decades. So, while coups are becoming less frequent, they are also becoming more effective.

| Decade |

Total coup

attempts |

Successful |

Success rate |

| 1950-1959 |

6 |

3 |

50% |

| 1960-1969 |

41 |

25 |

61% |

| 1970-1979 |

42 |

18 |

42.9% |

| 1980-1989 |

39 |

22 |

56.4% |

| 1990-1999 |

39 |

16 |

41% |

| 2000-2009 |

22 |

8 |

36.4% |

| 2010-2019 |

17 |

8 |

47.1% |

| 2020-2022 |

8 |

6 |

75% |

The greatest number of successful coups in Africa took place near the midpoint of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War rivalry stretching from 1946 to 1991. Coups were most prevalent in 1966, when seven took place. The next most-tumultuous year was 1980, when five were staged.

“During the Cold War in particular, there was effectively an unwritten rule saying if you controlled the capital, you were recognized as legitimate,” said Powell. Following that time, and especially since 2000, he said, the international community has been far less tolerant of coups. As a result, coup leaders are more likely to wait for circumstances in which the “status quo itself is terrible” or when they feel they can survive any negative responses to a coup, including sanctions.

Deposed leaders in Africa

1952

1954

1958

1960

1963

1963

1963

1965

1965

1965

1965

1966

1966

1966

1966

1966

1966

1966

1967

1967

1967

1968

1968

1968

1969

1969

1969

1969

1971

1972

1972

1973

1974

1974

1974

1975

1975

1975

1976

1977

1977

1978

1978

1978

1979

1979

1980

1980

1980

1980

1980

1981

1981

1982

1983

1983

1983

1984

1984

1985

1985

1985

1986

1987

1987

1987

1989

1989

1991

1991

1992

1992

1993

1994

1994

1994

1996

1996

1996

1997

1999

1999

1999

1999

2003

2003

2003

2005

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2012

2013

2014

2017

2019

2020

2021

2021

2021

2022

A look ahead

In October, the U.N.’s Guterres cited three main reasons for the increase in coups in 2021: strong geopolitical divides between nations; the COVID-19 pandemic’s economic and social impact on countries; and, finally, the U.N. Security Council’s inability to take strong measures in response to coups. For instance, Russia and China, both veto-holding members of the council, in late 2021 blocked it from imposing fresh sanctions on Mali’s coup leaders after those leaders announced delays in elections that would return the West African country to civilian rule.

The COVID-19 pandemic not only negatively affected countries most prone to coups by straining already tight budgets and placing further restrictions on populations already skeptical of their government, it also impacted world powers, which often take actions to help prevent coups. As a result, the high number of overthrow attempts during the pandemic years could prove to be an anomaly when the stressors of COVID-19 ease.

Powell said that while it would be surprising to see such high levels of coups continuing, “I am certain the coming years will see coups in higher numbers than what we had become accustomed to.”

He added, “The underlying causes of coups are present and worsening. Until these domestic dynamics improve, or regional or global actors can provide a solution, there is no reason to think coups should go away.”

Reporting and writing by Megan Duzor

Illustrations and graphics by Brian Williamson

Editing by Amy Reifenrath, Sharon Shahid, Salem Solomon and Carol Guensburg