Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: The Truth Teller We Never Deserved

By Alpha Amadu Jalloh

Author, Monopoly of Happiness: Unveiling Sierra Leone’s Social Imbalance

Recipient, Africa Renaissance Leadership Award

The African continent has lost one of her most powerful voices. A literary warrior. A truth teller. A man who wrestled language itself to liberate a people shackled not only by colonialism but by their own silence. The passing of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is not just the death of a Kenyan literary icon. It is the fall of a Baobab tree whose roots stretched from the highlands of Kenya into every village, every city, and every heart that dared to dream of a truly liberated Africa.

I remember being a young boy. Barefoot. Curious. Searching for identity in the dusty corners of Sierra Leone. It was there, in a quiet public library with more cobwebs than books, that I stumbled upon Decolonising the Mind. The title alone startled me. I read it like a sacred scroll. I didn’t understand everything then, but I knew I had found something that could feed the soul. That moment planted a seed in me. The belief that the pen could shatter chains, expose tyrants, awaken the masses, and restore dignity to a people bruised by history.

Ngũgĩ did not just write books. He wrote wounds. He wrote resistance. He wrote with fire in his belly and freedom on his tongue. At a time when many intellectuals in Africa chose to speak in metaphors and academic riddles, Ngũgĩ chose truth. Plain and unvarnished. He refused to be seduced by the Queen’s English when his mother tongue, Gikuyu, held the rhythm of his ancestors and the heartbeat of his people. That decision to abandon English and write in his native language was not literary bravado. It was rebellion. It was love. It was truth.

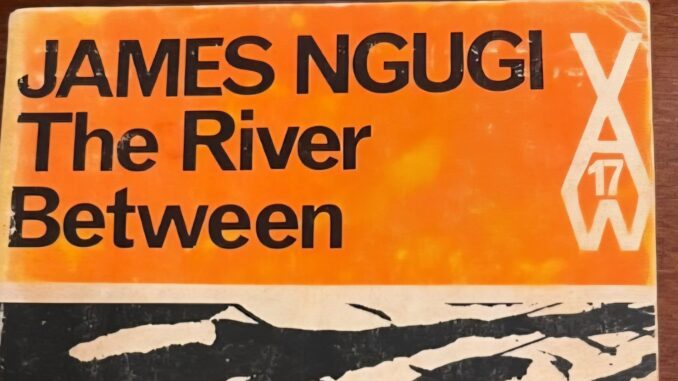

In Petals of Blood, Ngũgĩ took the promise of post-independence Kenya and exposed its betrayal. In The Trial of Dedan Kimathi, he resurrected the Mau Mau warrior spirit and demanded a new reckoning. In Matigari, he gave us a fictional hero who returned from war only to find that the oppressors had changed faces but not methods. How could a man with such clarity and such prophetic fire be ignored for so long?

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was not just censored. He was caged. He was exiled. He was cast out of the land he loved because he dared to remind it of its original promise. He spent years in exile not because he hated Kenya but because he loved it too deeply to lie about its flaws. He was not bitter. He never stopped writing. He never stopped teaching. He never stopped believing.

His pen made tyrants tremble and gave voice to the voiceless. To me, and to many like me, Ngũgĩ was not just an author. He was a mirror. He made me see that I too could write from Sierra Leone to the world. That I too could speak uncomfortable truths without apology. That I too could use the pen not as decoration but as a weapon. Sharp. Deliberate. Uncompromising.

When I began writing Monopoly of Happiness, my mind was flooded with the courage of Ngũgĩ. When I wrote about corruption, tribalism, the plundering of Sierra Leone’s resources, and the betrayal of our people by the very leaders they elected, I knew I was walking a path Ngũgĩ had long walked. A path littered with rejection, criticism, and censorship. But also with truth, purpose, and impact.

Ngũgĩ taught us that the role of the writer is not to please. It is to disturb. To awaken. To confront. To challenge those who drink wine while the children of the nation die of thirst. He spoke of language as memory, as identity, and as power. He reminded us that when we lose our language, we lose our soul. And that reclaiming it is not just cultural revival. It is political resistance.

Today, we mourn. But we must also remember.

Let us not bury Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o with mere praises. Let us resurrect his spirit in our classrooms, our parliaments, our media houses, our pulpits, and our streets. Let us teach his books not as relics but as roadmaps. Let us translate him into every African language and inscribe his words on every wall of every school. Let his ideas pierce the veil of comfort and mediocrity that has numbed too many African intellectuals.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is gone. But his truth remains. And if Africa is to rise, truly rise, it will be on the shoulders of those like him who refused to sell their conscience for applause or position.

As I write this, I imagine him resting somewhere among the ancestors. I imagine him smiling. Not because the world finally understood him, but because he never needed validation to speak the truth. He has returned to the soil. But his words have taken root in all of us.

I am because Ngũgĩ wrote. I dare because he dared. I speak because he showed that silence is betrayal. Farewell, father of African letters. Farewell, fearless scribe. May your pen never run dry in the afterlife.

May we, the living, write boldly enough to be worthy of your memory.

Rest in Peace the truth teller who no one listened to. Yet whose words outlived the silence of power.

Leave a Reply