PART 2

As the years went by I began to search for an actual photograph, convinced that one had to exist somewhere. When the internet appeared in the 1980’s, my search area grew vastly larger. Then, on 12 August 2012, 108 years after Bai Bureh’s death and 50 years after Mr. Marsh made the statue based on Green’s pencil drawing, an incredible thing happened. A photograph of the great warrior appeared on Ebay, the internet auction site. I was contacted by an old friend, William (Bill) Hart, who has done extensive field work in Sierra Leone and is an authority on the history and cultures of the counry. Bill had also seen the picture and was excited about the prospect of us acquiring it for the people of Sierra Leone.

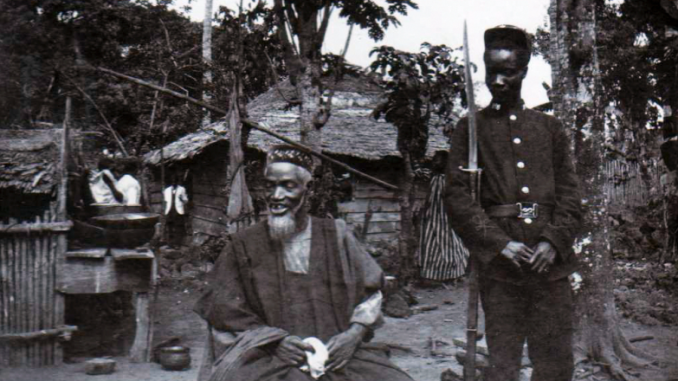

The Photograph of Bai Bureh

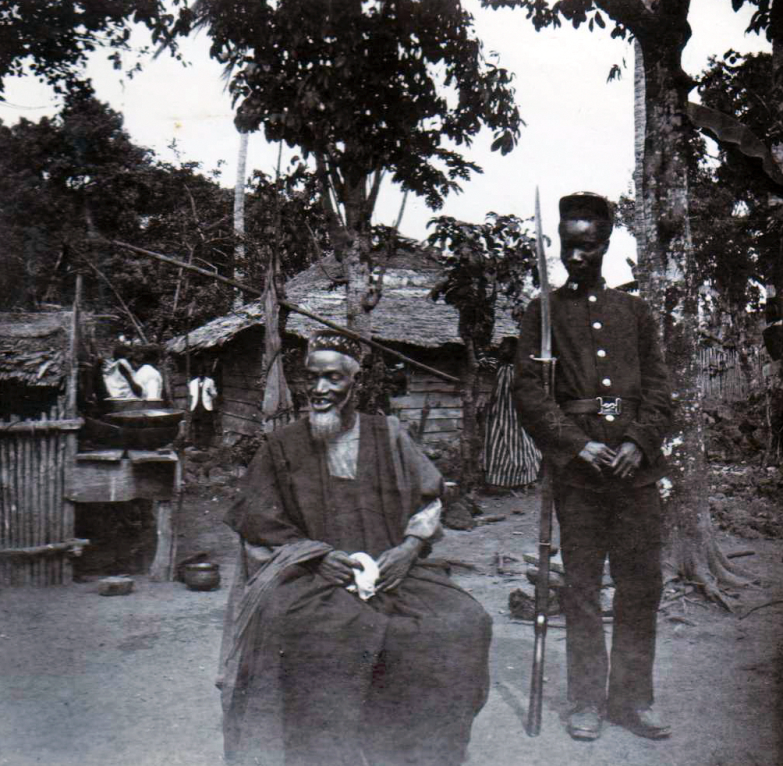

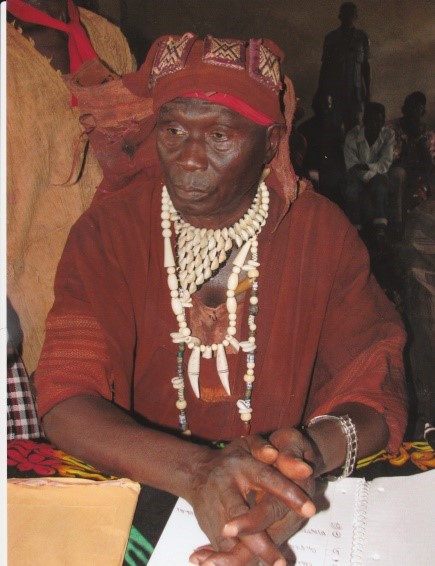

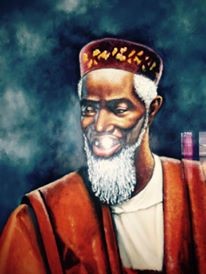

Hart described the picture: “It was a small black and white photograph of an elderly man, with white hair and beard, dressed in a ronko gown. That type of ronko with a slanting pocket on the chest is often worm by chiefs in Northern Sierra Leone today. The old man was also wearing a small round embroidered hat like those worn by Muslim elders in Sierra Leone. The old man was seated, facing the camera, and apparently at ease. He was sitting in the back yard of someone’s house, and there were other figures in the background, including a girl picking a papaya. And standing just behind the old man on the right side of the photo, there was an African policeman holding a very long rifle with a fixed bayonet. But he also seemed very much at ease, as he looked down at the seated figure with what appears to be an expression of admiration.”

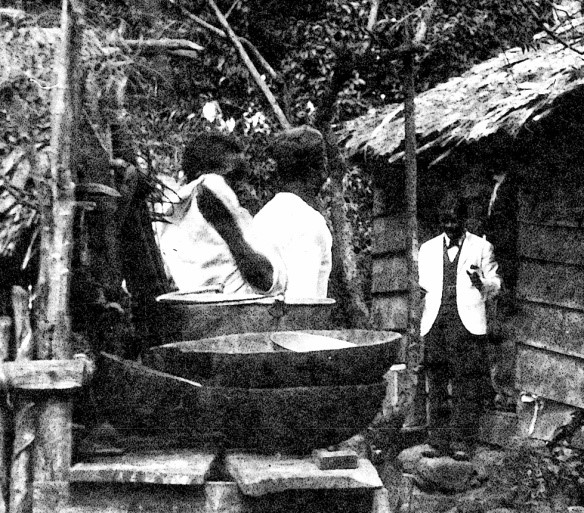

We later realized there were actually two women in the picture, the second one hidden by Bai Bureh’s head and three men in the background wearing white jackets who may have been servants.

A close-up of “The Servants”

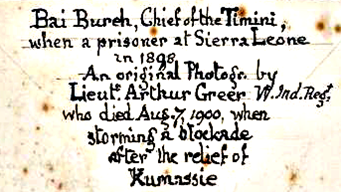

The Inscription beneath the Photograph

Below the picture was a hand-printed inscription which read:

Bai Bureh, Chief Of the Timini when a prisoner at Sierra Leone in 1898. An original photograph by Lieutenant Arthur Greer, West Indian Regiment who died August 7, 1900, when storming a blockade after the relief of Kumassie.

It was hard, after all the years that had passed, to realize I was actually looking at a genuine photograph of the famous warrior. Bill and I immediately agreed that we had to purchase the photo and make it available to Sierra Leone.

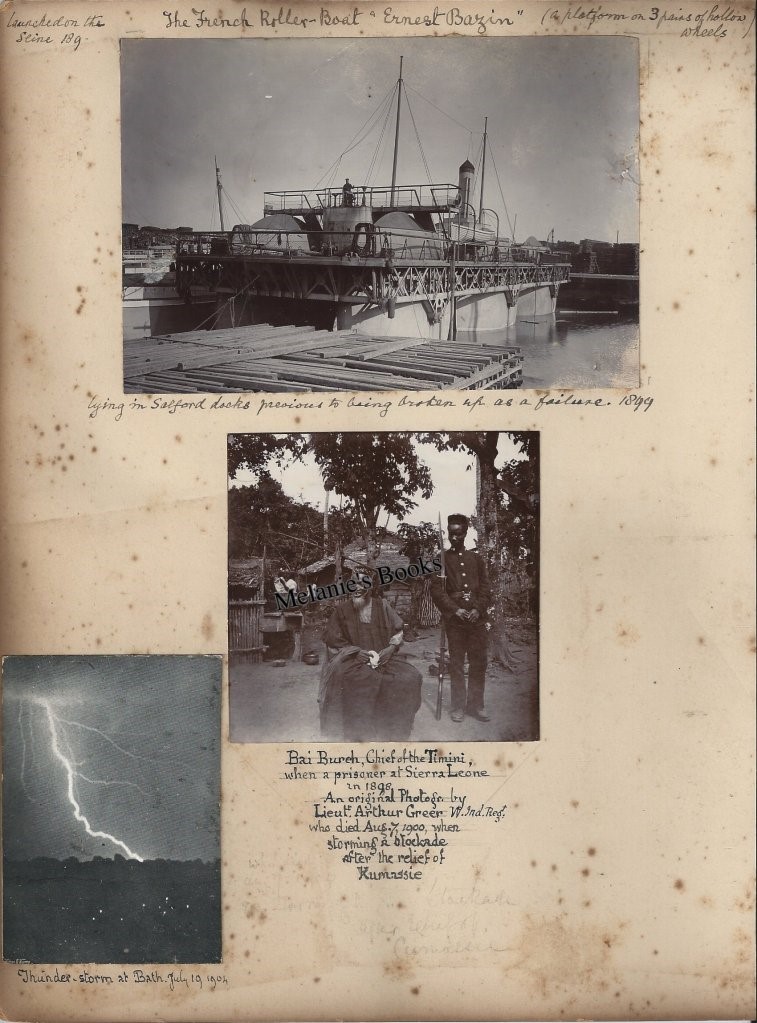

Bill went ahead and contacted the seller, but she couldn’t shed much light on the history of the photograph. She could only say it was attached to a page in a leather-bound photo album she had purchased at a sale in Norwich some months earlier. The album contained over a hundred original photographs of European royalty and military figures of different types from the period 1893-1913.

Here is the rest of the story in Bill Hart’s own words:

“I had better luck, though, tracing John Arthur Greer, the photographer. Records showed that Lt. Greer was in Sierra Leone at the time of the Hut Tax War in 1898. And he was, indeed, an officer with the 3rd West Indian Regiment, just as recorded in the photo album. And Greer died in 1900, exactly as described, in a night attack on a stockade outside Kumasi in the Gold Coast (modern Ghana) on August 7, 1900. This didn’t prove that the old man in the photograph was Bai Bureh, but since all the other information in the inscription was correct, it certainly suggested that the label “Bai Bureh, Chief of the Timini” was also correct.”

“But I did uncover an excellent lead. I learned that Greer was from the town of Lurgan in Northern Ireland and that his great-nephew Hugh Greer and his wife Adele still live in the family home, Woodville House, on the outskirts of town. As luck would have it, I live in Northern Ireland, and so I immediately contacted the Greers by phone. They were intrigued to hear about great-uncle Arthur’s photograph, and they agreed to look through their family papers to see if there was anything that might shed light on it.”

“A few days later they phoned me back, and I could hardly believe my ears: they had found a letter written by Arthur Greer to his sister, from Wilberforce (presumably Wilberforce Barracks in Freetown) dated May 1899, in which he described going with a fellow officer to visit Bai Bureh. By then, the old man was living as a political prisoner in a house in Ascension Town, near the house where the Asante king Prempeh I was also a prisoner. Greer asked the two deposed rulers if he could photograph them, and while Prempeh was aloof and refused, Bai Bureh was approachable and raised no objection. Prempeh had good reason to refuse. After his capture in the Gold Coast, he was forced to kiss the British Governor’s boot.

“Now, this was proof that the photograph was genuine beyond anything we could have hoped for, and I immediately contacted Gary Schulze with the good news that he could now bid for the photograph with complete confidence that it was exactly as advertised.”

The starting price on Ebay was £350, a reasonable sum for such a treasure, but there was no way to know how high the price would go. We agreed that I would begin the bidding and put a ceiling on my top bid comfortably above what we thought anyone else would pay. In the meantime Bill Hart agreed to check out the information accompanying the photograph to see whether we could establish that it was genuine.

The day the auction closed there was only one other bidder and the price had gone up to £778. With a half hour to go, I put in a bid for £3200 certain that there was no way the other person would top that. Then I dozed off. When I woke up I found that the auction had ended and a last-minute bidder had jumped in and bought the photograph for £3500. I immediately panicked, afraid the picture would disappear into someone’s private collection and never be seen again. I emailed the seller asking her to contact the buyer and tell him I would pay him twice what he bought it for.

The buyer turned out to be a London-based Frenchman who deals in vintage photographs and had bought the picture on speculation. Realizing how anxious I was to get it, he made a counter-offer of £10,000, finally agreeing to £7,000. And so, on August 26, 2012 I finally became the owner of Lt. Arthur Greer’s photograph of Bai Bureh.

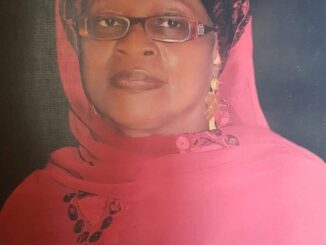

One of the first people I notified was Joe Opala. Joe was excited to hear that the photograph had finally been purchased and he developed an elaborate plan for me to introduce the photograph when I visited Sierra Leone. He asked the Deputy Coordinator of the Bunce Island Project, Isatu Smith, to handle the logistics.

Before leaving New York, I had a dozen large prints of the picture made and framed for presentation to His Excellency President Ernest Bai Koroma and other dignitaries in Sierra Leone. To my amazement the tiny picture enlarged remarkably well, thanks to the photographic skills of Peter Andersen who restored the original.

Upon my arrival in Freetown on April 21, 2013, an initial press conference was held at the Ministry of Tourism and Cultural Affairs followed by additional meetings at the British Council and the Sierra Leone Museum. The Minister of Tourism & Cultural Affairs, Peter Bayuku Konteh, was also very excited by the discovery and wanted to promote it as much as possible. The photograph generated a great deal of interest throughout the capital and the press release we sent out was reproduced in many of the city’s newspapers. Everyone wanted to see what Bai Bureh really looked like. There were a few skeptics who questioned its authenticity but they were quickly silenced when they were told about the Arthur Greer letter that Bill Hart had discovered.

Article in “The Nationalist”, May 2, 2013

On May 2nd I left Freetown in a wooden boat, or “pampa,” for Shenge where I was installed in an elaborate two-day ceremony as Honorary Paramount Chief Pieh Gbabiyor Caulker II of Kagboro Chiefdom. I presented a framed copy of the photograph to Paramount Chief Doris Lenga Gbabiyor Caulker II and her Section Chiefs at the court barri.

Once back in Freetown, promotional activities continued with presentations at Fourah Bay College, the American International School, the U.S. Embassy, and Albert Academy. The Principal assembled the entire student body in front of the building where I told them how the picture had been found and then presented a framed copy to the school. At the end of the presentation, the boys mobbed around me to get a better look at the photograph they had heard so much about in the media. I also presented a copy to Former Sierra Leone President Alhaji Ahmad Tejan Kabbah at his residence in Juba.

With U.S. Ambassador Michael Owen

With Former President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah

Presenting the photograph to the student body, Albert Academy

Unveiling the Bai Bureh photograph at a press conference at the British Council.

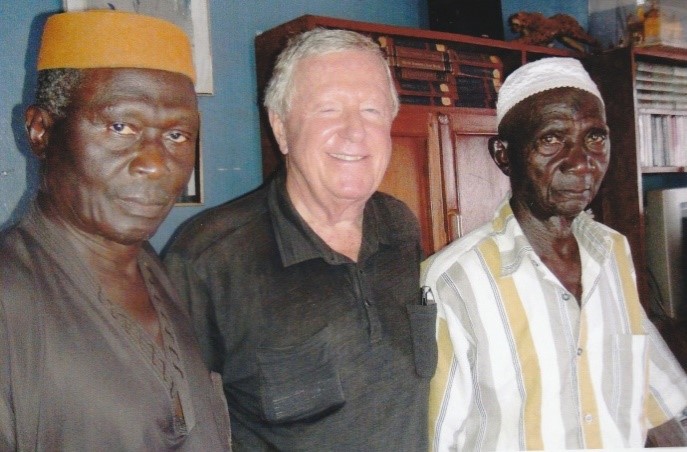

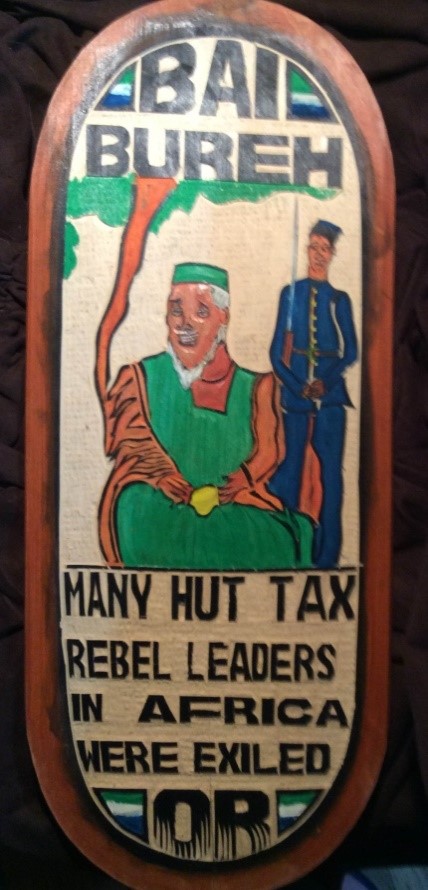

I then received a call from Isatu Smith. She said the Paramount Chief of Kasseh and the elders of the Kasseh Descendants Association were upset that they had not been brought into our plans from the beginning. They felt they should have been invited to greet me at the airport when I arrived from the United States. Isatu and I went out to Wellington to meet with Paramount Chief Bai Bureh Sallu Lugbu II of Kasseh Maconteh Chiefdom at his Freetown residence to extend our apologies. He introduced us to an elderly gentleman, Amara Kamara, who turned out to be Bai Bureh’s great grandson. The chief, who is also a Member of Parliament, invited me to visit Kasseh where he said they would hold a big celebration in honor of the newly-discovered photograph and take me to Bai Bureh’ grave to pay my respects. Before leaving, I noticed a wooden plaque hanging on the chief’s living room wall depicting Lieutenant Green’s old drawing of Bai Bureh. I told him I would give him a framed copy of the new picture to replace it with.

With Paramount Chief Bai Bureh Sallu Lugbu II of Kasseh and Amara Kamara in Wellington

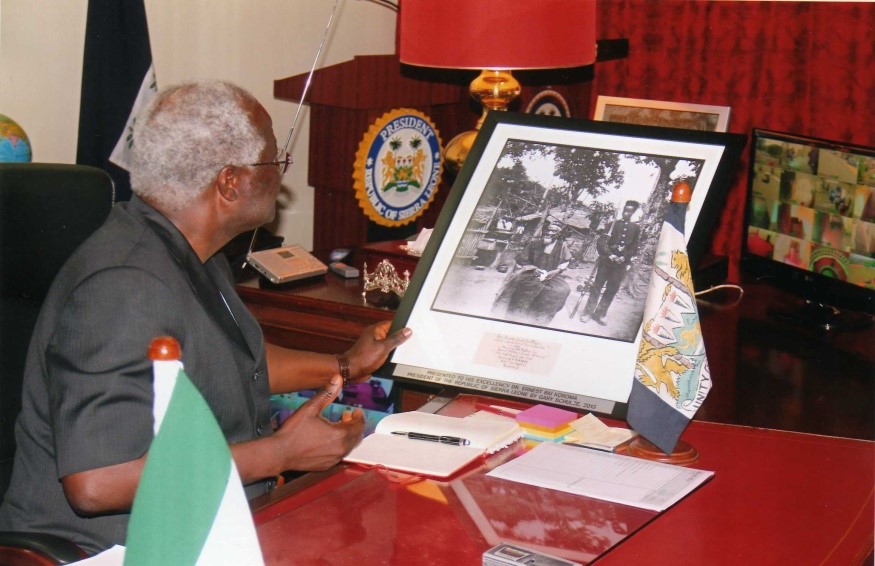

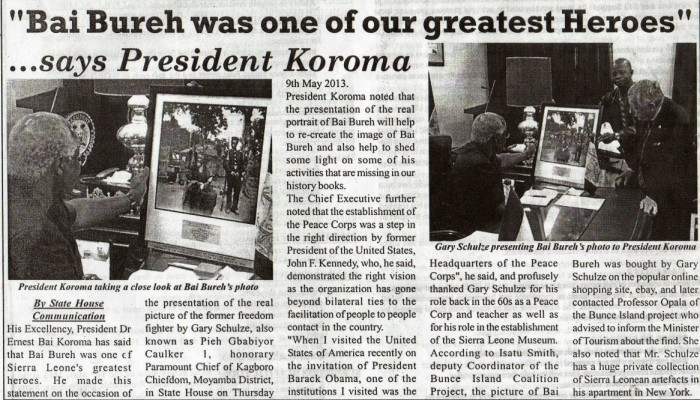

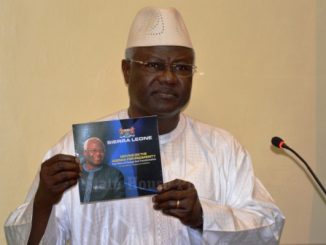

On May 10, together with Paramount Chief Caulker, Peter Andersen, Lucy Sumner, Isatu Smith, and former Foreign Minister Shirley Gbujama, I presented two framed copies of the photograph to President Koroma at State House. Isatu introduced us and explained how the picture had been discovered. In response, the President said that Bai Bureh was one of Sierra Leone’s greatest heroes. He went on to say that “the presentation of the real portrait of Bai Bureh will help to recreate the image of Bai Bureh and also help to shed some light on some of his activities that are missing in our history books.” I’ve been told since that President Koroma is extremely proud of the picture and keeps it close by in his office in a place where visitors can see it.

Presenting the photograph to H.E. President Ernest Bai Koroma at his office in State House

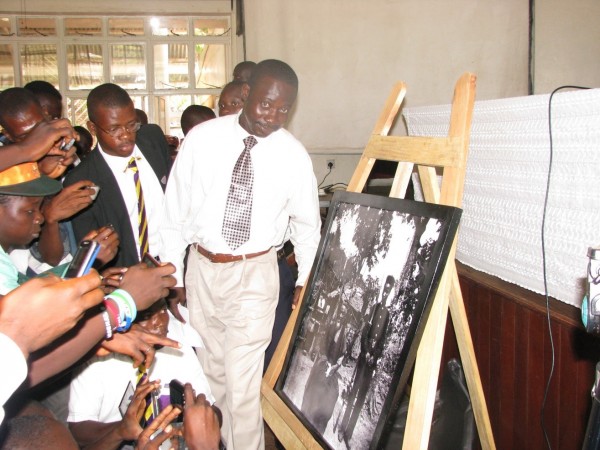

The following day we had a ceremony at the Museum to officially unveil the photograph and launch the “Face of Bai Bureh Photo Exhibit”, attended by VIP’s including the Minister of Tourism, the Chairman of the Monuments & Relics Commission, the Director of The Central Bank of Sierra Leone, and other dignitaries. The Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Tourism served as M.C. and the guests were entertained by the Freetown Players and Lansana Keleng & Company. The Bank Director announced that future currency would bear the newly-discovered image of Bai Bureh.

The old Bai Bureh statue Mr. Marsh created 50 years had been carried out onto the lawn in back of the Museum and placed next to an old drum which was said to have actually belonged to the chief. The statue stood in the hot sun with a faint smile on his face next to a gigantic blow-up of the newly-discovered photograph resting on an aisle. It was almost as if he was thinking, “Well now you all know what I really looked like.” Oddly enough the resemblance between the two faces was startling, especially since Marsh had worked entirely from his imagination.

Reunited with my old friend, Bai Bureh at the museum fifty years later

An old sacrificial pot was placed in front of the Marsh statue and libations were poured to honor the ancestral spirit of Bai Bureh by Paramount Chief Bai Bureh Sallu Lugbu II of Kasseh, Paramount Chief Doris Lenga Kroma Caulker of Kagboro Chiefdom, accompanied by Bai Bureh’s great-grandson, Amara Kamara, and Elders of the Kasseh Descendants Association.

Since I was now an Honorary Paramount Chief, they invited me to join them.

Paramount Chiefs & Kasseh Elders pouring libations in front of Mr. Marsh’s statue at the Museum

After the ceremony, the Bai Bureh photograph went on public display at the Museum. And just as Mr. Marsh’s statue in 1963 attracted crowds of people, hundreds of Sierra Leoneans came to see the newly-discovered picture.

A few days later, accompanied by the Minister of Tourism, Isatu Smith, and Lucy Sumner, I journeyed to Kasseh, Bai Bureh’s home village in the Port Loko District, to visit his grave. En route we stopped and were taken into the bush and shown bronze engraved markers indicating the burial site of British soldiers who were killed by Bai Bureh’s warriors during the 1898 Hut Tax War. They were all members of the same West Indian Regiment that Lieutenants Henry Edward Green and Arthur Greer had belonged to.

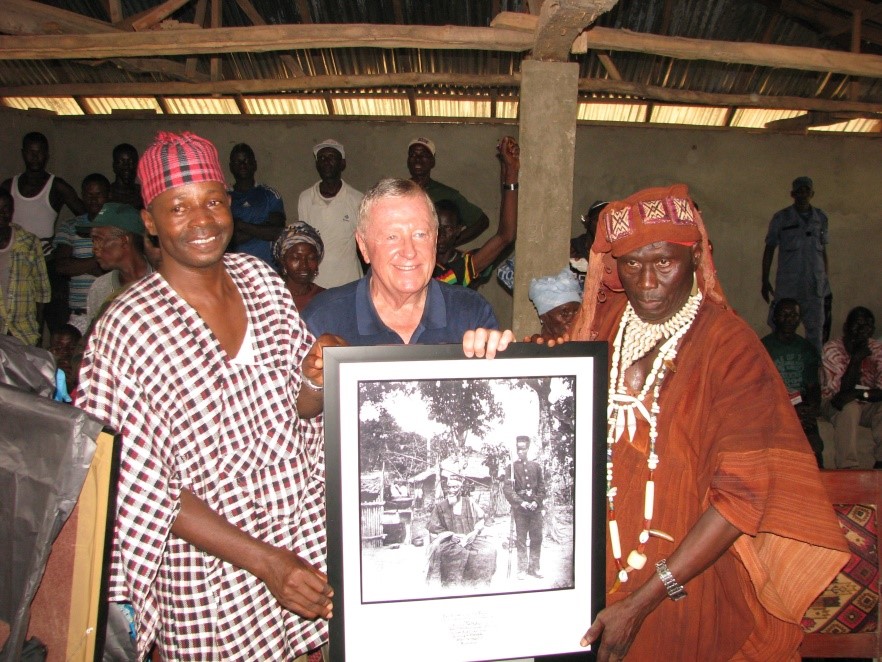

Upon our arrival we were met by hundreds of Temne people in a welcoming procession with drumming led by the Paramount Chief and village elders. Some young men dragged out a wooden sculpture of Bai Bureh modeled after the old Lieutenant Green drawing. It had apparently been kept in a shrine somewhere in the village.

The Elders of Kasseh welcoming us led by the Paramount Chief And Chiefdom Speaker

A statue of Bai Bureh kept in a Kasseh village shrine

P.C. Bai Bureh Sallu Lugbu II

The Minister and I, together with Isatu Smith and Lucy Sumner, were then led barefooted into the bush with white bandannas around our foreheads to visit Bai Bureh’s grave. Moving along the path, we often came across white sheets stretched across the trail with an opening through which we had to pass backwards on our way to the grave.

At the site the tribal elders began chanting,”Lontha, Lontha, ka rabai” (“The End, The End”), the ancient Temne veneration, as they poured libations on the grave. They spread rice on the ground and placed a chicken next to the grain, waiting anxiously to see if the animal would eat the rice. When the bird began to feed, the elders knew the ancestral spirits had accepted their offerings. “We have brought a white man here”, said Paramount Chief Bai Bureh Sallu Lugbu II, speaking in Temne. “This white man came to us with the true picture of you so now we know what you really looked like. Now, he is an American, not an Englishman”, continued the chief, as he addressed his famous ancestor by his warrior’s title, “Kebelai,” meaning “the one who is never tired of war.”

We had to wear white bandanas on our heads to enter the Sacred Bush

As we emerged from the sacred bush with the chief and his elders and made our way back to the center of the village, the Paramount Chief confessed to me that I was the only white person ever allowed to visit Bai Bureh’s, an honour they had bestowed upon me for finding the photograph and bringing it to Kasseh.

The Minister and I presenting the photograph to the Paramount Chief and people of Kasseh

The following year I returned to Sierra Leone and found that wooden figures and plaques were beginning to appear in the market-place patterned after the image in Arthur Greer’s photograph. In addition, a children’s book had been published, “Bai Bureh And The Hut Tax War”, written by Kande-Bura Kamara, with drawings of the warrior based on the photograph. The original pencil drawing by Lieutenant Green and later the museum statue I commissioned had caught the public’s attention at different periods in Sierra Leone’s history. But now the new photograph was beginning to take its place. And President Koroma displays the framed photograph in his office at State House where, I’m told, he shows it proudly to visitors.

The photograph inspired new carvings and drawings of Bai Bureh

The conclusion to the story of the “The Three Faces of Bai Bureh” was best summed up by Bill Hart who wrote:

“Sierra Leoneans can now see their great hero not just in a drawing or a cartoon, or a woodcarving, or a manikin dressed up to look like a real person. For the first time since he died more than a hundred years ago Bai Bureh’s people can look into his face and gauge as best they can what kind of man he was, and imagine how it would have been to greet him, as one would a paramount chief today, bowing slightly, and shaking his hand and speaking to him respectfully.”

_____________________________________________________________________

This article relies for some of its content on a booklet titled, The Face of Bai Bureh: A National Hero Emerges from the Darkness, with contributions by Gary Schulze, William Hart, and Joseph Opala. Printed under the authority of the Ministry of Tourism & Cultural Affairs, it was made available to the public when the Bai Bureh photograph was unveiled in 2013.

Special thanks to the following people: Peter Andersen, Paramount Chief Doris Lenga Kroma Caulker II, Musa Coker, William Hart, Alpha Kanu, Peter Bayuku Konteh, Paramount Chief Bai Bureh Sallu Lugbu II, Joseph Opala, Ambassador Michael Owen, Julius Parker, Alhusine Sesay, Isatu Smith, Lucy Sumner, David Wright. And in memory of Dr. M.C.F. Easmon, J.D. Marsh, Henry Edward Green, and Arthur Greer.

Thanks also to the U.S Peace Corps for giving three of the people involved in this story the opportunity to enrich our lives by serving in Sierra Leone – Peter Andersen, Joseph Opala, and the author, Gary Schulze.