By SAM HILL of NEWSWEEK Magazine

In 2018, President Donald Trump asked, “Why are we having all these people from shithole countries come here?” That not-so-subtle implication—poor people from poor countries are inferior to rich people from rich countries—properly outraged most people. But the question contains an uncomfortable truth. Many countries are indeed terrible places to live, especially for those on the bottom rungs of the socio-economic ladder. There’s no official definition of Trump’s “shithole,” but we know which ones he means. Countries that are poor, violent and mostly brown. Guatemala. Sudan. Yemen. Myanmar. Niger. Haiti. Bangladesh. Pakistan. Although most of the countries that fit Trump’s definition are in sub-Saharan Africa.

It is tempting to build a wall and tell developing countries to figure it out on their own, like our president would have it. Except we can’t. We have no way to insulate ourselves from their problems: Deforestation. AIDS. Ebola. Terrorism. Drugs. Gangs. Illegal immigration. Ecological disasters. Any more than they have a way to protect themselves from ours: Climate change. Worker abuse. Toxic waste. Sexploitation. No wall will keep our worlds apart.

So what do we do? Increase aid funding for the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals? Tax breaks to encourage private investment?

Preferential access to the western markets? Expand Peace Corps? All of the above and more? In a career in international business, I have worked in dozens of countries in Europe, Australasia, Africa and the Americas. I’ve worked for the world’s largest corporations as well as NGOs like the World Bank. In the process, I’ve talked to literally hundreds of development experts, executives and government leaders about development. None believe more aid will work.

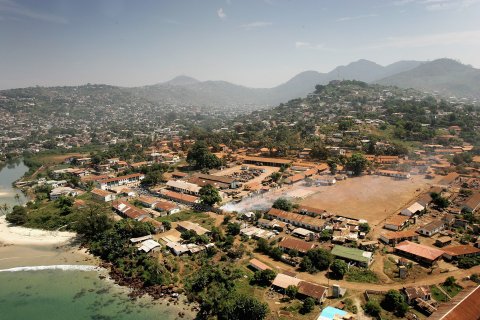

To find out what would work, I headed to Africa. In particular, Sierra Leone, a small country on the west coast of Africa famous for Ebola and blood diamonds. It is one of the poorest nations in the world, 184 out of 189 on the U.N.’s Human Development Index, far below countries like Haiti and Iran. For centuries, Sierra Leone has been the epitome of hopelessness. In 1827, popular author Frederick Chamier wrote he’d travelled widely and, “never knew and heard mention of so villainous and iniquitous a place.”

Robert Kaplan, 25 years ago, used it as the proof case in his influential article “The Coming Anarchy.” Central America is well-off compared to Sierra Leone.

But it is also a country that could be a model for economic revival.

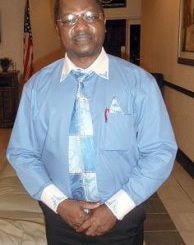

My journey began in the capital city of Freetown, made famous in the movie, Blood Diamonds. I opted to travel upcountry as poor locals do, using public transportation and on foot, eating whatever I could find along the way. Prominent businessman Alfred Gborie called that, “A very bad idea.” He was right.

Sierra Leone is roughly the size of South Carolina and roundish, with two Yoda-like ears that jut out on either side. The left ear is the Western Area where Freetown is located. My destination was the right ear, the rough border town of Kailahun, where both the war and Ebola started. The few Americans who travel beyond Freetown usually hire an air-conditioned Land Cruiser and driver. It’s not just about comfort. Smaller roads are a nightmare of rocks, ruts and mud. Vehicles are falling apart. Drivers are often drunk. And there are still a lot of unemployed fighters around. Everyone knows visitors carry wads of cash because electronic payments aren’t used upcountry. Kaplan called West African cities at night “some of the un-safest” on earth.

But I wanted to see the country as its residents live it, see it and travel it—as I saw it in the Peace Corps.

So, I started my journey on a motorcycle taxi. The driver wore a football helmet with no strap. It was too large and slipped around on his head. Occasionally he reached up with one hand and gave it a quick rotation, twisting the eyehole around so he could see. We weaved and darted between vehicles, my legs brushing against bumpers and sides of cars, swerving around pedestrians, accelerating quickly into seemingly impenetrable walls of traffic and somehow emerging from the other side.

Four vehicles later, we squeezed into an already overloaded poda-poda, a minivan. I sat on a fold-down seat. Next to me on a small wooden stool crouched the teen whose job it was to tout, load passengers and collect fares. Every few hundred yards, he jumped out and handed me his stool to hold until we started up again. We wound our way down the mountain side. As we rounded each curve the top-heavy vehicle rocked outward, and I stared out over the precipice onto the tops of the houses clinging to the sides of the steep ravines.

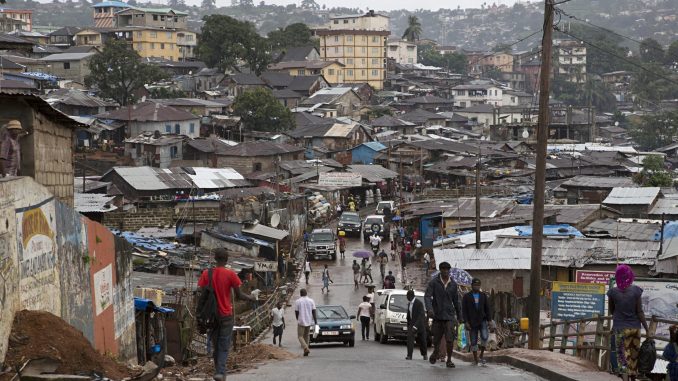

The poda-poda left us at Pee Zed, named after a trading house once located there. Pee Zed was jammed with stalls and people. Building walls were black with soot and the street ankle deep in trash. A sour stench rose from the open gutters. Vendors carrying everything from electronics to clothing to hardware jostled, shoving samples toward prospects. Lining the street were verandas crowded with shops, banners and customers. They looked over fragile-looking railings at the mass below. The vendors carried small battery-powered bullhorns with recorded messages like “The best of the best is here and not to be missed! Best price! Best price!” Vehicles honked their way through the crowd. It was deafening.

We caught another minivan to an outer suburb where we squeezed onto a rickety bus. Thirty five people into 20 seats. Kids slept on the floor beside wicker baskets holding chickens. My legs were jammed into a space so narrow one foot rested on top of the other. It all stunk of sweat, bad food and chicken droppings.

The bus wheezed slowly up hills, stopping to disgorge or take on passengers. When it started raining, I could feel the rear end sliding around. A kid with a dirty rag wiped the condensation from the windshield in front of the driver. It was one of the worst journeys I’d ever taken—uncomfortable, dangerous, interminable. It took 13 hours and nine vehicle changes to get 200 miles, riding late into the night, jammed into a sweltering bus. But for poor people in a poor country, it was just a typical day.

Nothing much had changed from my Peace Corps days.

“This country has great potential. Look at Singapore. It’s even smaller and has no natural resources at all,” a U.S. official told me. It’s a facile and misleading answer, a bit like telling a third grader anyone can be president.

Why did their fates diverge so spectacularly? There are entire journals devoted to explaining why Sierra Leone and other African countries have fallen behind. The theories fall into three buckets. It’s the fault of Africans. It’s white people’s fault. It’s nobody’s fault.

Some believe Africans and African culture are to blame. A few come right out and say it, like President Trump, who wants more immigrants from Norway and for outspoken African Americans to go back where they came from. Others tend to be more, uh, diplomatic. But they get their message across. In Commentary magazine, Daniel Schatz attributes the economic success of Sweden to being populated with Scandinavians who have a “Protestant work ethic.” In other words: very white people.

A less detestable argument is that Africans have chosen poor leaders and built weak institutions. Many African leaders follow the “big man” model, lavishing patronage and refusing to be bound by law or convention. Factions swap control of the government, and when they are in power take their turn at the public trough. Elections are not honest and those in power do not abide by their results. There is bad governance. Public funds are dispersed on ill-founded projects. There is no accountability. The public sector is corrupt. Economies are hampered by bad policies which inhibit competition and create conditions that are unfavorable for investment.

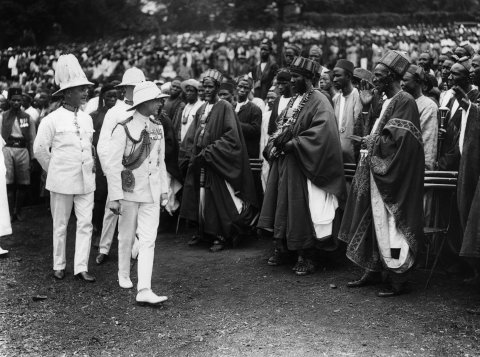

To many, though, this is blaming the victim. They point the finger instead at Europeans and even Americans. The feeling is widespread amongst aid professionals and Africans themselves. In the Congo, a reporter for El Mundo was threatened by militiamen who shouted, “You whites are the cause of everything bad that happens in Africa.” Not everything perhaps, but plenty: Slavery, colonialism, destabilization of governments during the Cold War.

As Americans are still experiencing 400 years on, slavery corrodes everything it touches. More than 12 million Africans were kidnapped and exported as slaves. They were purchased with guns, which led to endless internecine conflict. Colonialism was almost as destructive. When the Europeans met in Berlin in 1884 to divvy up Africa, boundaries were set based on European claims and natural dividers, like rivers. The new colonies contained many different ethnic groups and ethnic homelands stretched across colonial boundaries, confounding notions of nationhood. Sierra Leone has at least 16 different ethnic groups. It was a recipe for fragmentation and perpetual conflict.

There’s a third explanation for Africa’s predicament: “It’s nobody’s fault.” Jared Diamond and Jeffrey Sachs have written bestsellers arguing that the real villain is geography. In Diamond’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Guns, Germs, and Steel, he argued that Asia had wheat and barley and animals like horses that could be domesticated, while Africa had zebras, which cannot. Diamond posited that the Sahara Desert created a physical barrier to advances spreading southward. Sachs has argued that the causes are geography and climate, e.g., being landlocked and tropical.

The problem is that just like Einstein failed in his search for a “unified field theory,” no one has managed to come up with a compelling Grand Unification Theory of Why Africa is Screwed Up. The most likely answer is that it’s not a single factor, but an accumulation. Take the Singapore comparison. It is tropical. It has multiple ethnicities and became independent from Britain at roughly the same time as Sierra Leone. Corruption is endemic in Singapore’s part of the world. It doesn’t have many Scandinavians. So why did Singapore succeed and Sierra Leone fail?

There are differences. Singapore is on a major trade route. It embraced capitalism well before most developing nations, which gave it a head start over Africa. The world was a different place then, e.g., outsourcing was just starting. And Singapore had Lee Kuan Yew. Singapore’s first prime minister, Lee was arguably one of the greatest leaders of the 20th century. He was also, in the words of Glenn Hubbard, former dean of the Columbia Business School, “sui generis,” or unique.

Sierra Leone provides a compelling case for each of the three theories: Bad Africans; bad Europeans; or bad luck. Take your pick. The democracy installed by the British proved fragile and was torn apart by ethnic rivalries. Siaka Stevens became president in 1971. Sierra Leoneans call his time in office “the 17-year plague of locusts.” He abolished democracy and institutionalized graft on a scale rarely seen even in Africa—kickbacks, embezzlement, and most of all, stealing diamonds. The country is lucky to be rich in mineral resources, but unlucky that those include diamonds, which are absurdly easy to steal and transport. A briefcase of high-quality diamonds is worth $125 million, about the same as a tanker of crude oil. Stevens became one of the richest men on the continent.

In 1991, forces under the command of a former political prisoner, Foday Sankoh, crossed the Liberian border, starting the civil war. Unemployed young men flocked to Sankoh for the promise of a paycheck. The war was an 11-year smash and grab. Even the good guys looted and stole. Locals called soldiers “so-bels,” soldiers by day who posed as rebels at night to commit rape and robbery. Nigerian soldiers were there as part of the Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group, or ECOMOG. Locals said the acronym stood for “Every Car or Moving Object Gone.” Atrocities were committed by all sides. Rape and murder. Cannibalism. Mutilation. And after the war came Ebola.

Many of the effects of the war and Ebola are still being felt today, a generation later. Amputees limp along on crutches made of sticks. Literacy is below its prewar level because 1,270 schools were destroyed and 67 percent of children were forced to leave school. Cities and larger towns swelled as the population fled the countryside. Once the war was done, many people remained, straining already insufficient infrastructure. Business left. Records were lost. There is still no mail service. The economy is barely kept afloat by aid, increasingly provided by China, a common trend in Africa. (Which is perhaps why the Trump administration shelved plans to close OPIC, the agency that facilitates private investment in developing markets.) And those are just the visible effects. Ten thousand children became soldiers. A U.S. diplomat said the country is suffering from “national PTSD.”

The details may vary, but much of Africa is in a similar state. Sixty-eight percent of African countries are in the bottom quartile of GDP per capita. Only one sub-Saharan nation makes it into the top quartile, Equatorial Guinea, and that’s just barely. No sub-Saharan African nation makes it into the top tier of the U.N. HDI. African nations dominate the bottom, with 32 of the 48 slots. The best country in sub-Saharan Africa, Botswana, is seven slots below the Dominican Republic and over 50 places below Iran. The Fragile States Index rates only one country on the entire continent as “stable.”

Some insist it’s not as bad as the numbers indicate. Paul Collier, a world-renowned international development expert at Oxford, told me there are bright spots: Botswana. Ethiopia. Ghana. Rwanda. You can add South Africa to the list, too. The U.N. claims the Millennium Project (and its successor) have been successes.

Others are even more bullish, like Jake Bright and Aubrey Hruby in their book, The Next Africa: An Emerging Continent Becomes a Global Powerhouse.

That isn’t what I found in Sierra Leone. I found a country not a whit better off than the one I’d left almost a half century before. And a place where people have not only lost just homes, lives and limbs—but even their memories.

I discovered that when I visited the small bush village of Nyandeama. I was there to search for old Peace Corps friends Bockrie Sallu and his daughter. The last I heard from Bockrie, via a letter to a mutual friend, was in 1995. He said the rebels had attacked and his family was safe and accounted for, except for “my daughter Jeniba, who have been lost and up till now I have not set eyes upon her.”

I’d brought some pictures taken by my friend Guy Washington, another former Peace Corps volunteer. I pulled them out for the chief of the village. Without speaking, he extended his hand. I handed him the entire stack. He went through each one slowly, handing it to the person beside him as he finished. His hands began to shake. People shouted. Soon a crowd formed. They handed the pictures around, tapping excitedly when they recognized a relative and laughing. People handled each picture reverentially, carefully, by the edges. They stared, some wiping away soft tears, and then handed it on to the next person. It was a wonderful moment.

I got a similar reaction in the village where I’d been stationed, Majoe. When I left, the chief gave a speech. “Thank you for coming. Thank you for the gifts you have brought us. We will use the money well. But most of all, thank you for bringing those photographs. You have given us back our memories.”

Sierra Leone’s economy is “donor-driven,” i.e., dependent on foreign aid, both from Official Development Assistance and private. The country is inundated with aid workers and missionaries who’ve come to build schools and roads, install wells and solar systems and teach. Every public structure has a sign saying it was built by an aid agency. The problem is that aid doesn’t work. It alleviates the pain of poverty, but doesn’t cure it. Sierra Leone’s been getting aid continuously since 1787, when Freetown (Granville) was established with funding from the London-based Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor. John Lahai, a Sierra Leonean who’s worked on numerous aid projects, explained the problems. Aid is wasteful, inefficient, encourages corruption and destroys self-reliance on the part of recipients.

But it’s not easy to end aid dependence. Collier estimates that aid has added around 1 percent to the annual growth rate of the poorest countries over the past 30 years, and that without aid, many of them instead would have suffered severe decline. If aid to the continent were simply cut off tomorrow, millions would starve.

There’s an obvious alternative. Former ambassador and head of the U.N. mission in the Congo, Roger Meece, says the answer is, “jobs.” And everyone agrees that the way to create jobs is a strong private sector. The question is: How to get there?

One suggestion is to go small. In 1961, Africa was self-sufficient in food production. By 2007, there was a 20 percent shortfall. Ghanaian economist George B. N. Ayittey wants to go back to that “golden age of peasant prosperity.” He espouses a bottom-up development model built around villages and agriculture. His plan calls for providing basic infrastructure and using microfinance. Many aid workers support this approach. Peggy Murrah, head of the Friends of Sierra Leone group, describes that vision as the “sweet life.”

While appealing, that approach is probably impractical. Microfinance makes for heartwarming stories, like those in Roger Thurow’s acclaimed book, The Last Hunger Season. But Collier says it is too small to make a difference. There’s limited land available to support an expansion of subsistence farming. Much subsistence farming is slash-and-burn, where farmers clear and burn new forest each year, which is an ecological nightmare. And there’s an even bigger problem: Is peasantry what people want? Subsistence farming is a life of poverty where success means having enough to last until the next harvest. It’s backbreaking, brutish work. None of the young people I spoke to wanted any part of it.

The alternative is to create a more modern, urban society funded by a strong private sector, the Singapore Solution. In Rwanda, President Paul Kagame has set out to do that. He’s taken aim at things that turn off investors like poor sanitation and corruption. He’s invested in infrastructure and technical training and installed the rule of law for business, ensuring enforcement of contracts. He’s worked to build Rwanda into a financial services and information technology provider. The net result is that Rwanda is ranked 29 in the world by the World Bank for ease of doing business. According to Patricia Crisafulli, who co-wrote Rwanda, Inc., it’s working.

Might that formula work for other small African nations like Sierra Leone? Perhaps. Rwanda and Sierra Leone are similar in size, population, demographics. Both have ethnic friction and are recovering from conflicts. However, the Rwanda solution comes at a price. Freedom House scores Rwanda very low because Kagame has created a one-party state, been re-elected with a suspicious 98.8 percent of votes cast and changed the constitution to allow him to serve until he’s 77. Many Sierra Leoneans I talked to would take that deal: prosperity for democracy. But the challenge is finding the right leader. It’s proven easy for developing nations to recruit dictators, but not so easy to find a Lee Kuan Yew, as Singapore did. As Collier says, “If autocracy were a formula for success, African nations would be rich.”

The recently-elected president of Sierra Leone, Julius Maada Bio, is trying to embrace the private sector. He’s toured the U.S. and Europe telling business leaders that Sierra Leone welcomes investment. But it’s not that simple. For business to work, it needs the right conditions. A free market without rules dissolves into a kleptocracy. The Heritage Foundation publishes an annual ranking of “Economic Freedom,” which is in effect a measure of how easy it is to be a capitalist or entrepreneur in each country. At the top is Hong Kong, with a rating of 90.2. The U.S. scores 76.8 and Sierra Leone only 47.5, putting it 167 out of 180 ranked countries. It ranks 42 out of 47 in Africa.

According to the Foundation, “A deficient legal framework leaves property rights and contracts insecure. There is no land titling system.” There’s also no established and transparent way to resolve commercial disputes. And there’s still the elephant in the room: Corruption. Sierra Leonean leaders know this. They’re smart and well-educated. However, things like titling land are huge undertakings. And, not everyone’s on board with change. As Daron Acemoglu, MIT professor and co-author with James Robinson of the bestselling Why Nations Fail and the forthcoming Narrow Corridor: States, Society, and the Fate of Liberty, says, “While bad government may not work for the majority, it always works for someone, and those it works for are usually those at the top.”

That’s the problem for most African nations. The conditions for a strong private sector don’t exist—legal framework, infrastructure, know-how. To address that, in their book, The Aid Trap, Glenn Hubbard and and co-author William Duggan suggested a Marshall Plan for Africa. It’s a top-down option that calls for developed nations to fund a large burst of aid to build market economies across the continent. It’s analogous to what the U.S. did to support Western Europe’s recovery from World War II. That assistance took the form of investments in infrastructure, loans and technical exchanges. A watered-down African version was embraced by Angela Merkel in 2017 as a way to slow the stream of economic refugees flooding into Germany. Her logic was that if conditions were better back home, fewer migrants would come to Europe. Presidential candidate Julian Castro has made a similar case for a Marshall Plan for Central America.

Hubbard argues it would work because it would be focused on the private rather than the public sector. Hubbard believes it could be tied to changes like cutting red tape that would create the environment for economic growth.

Building a strong private sector is the only answer that addresses the developing world problem in a substantive and permanent way. It isn’t an easy solution. Corruption is hard to root out. And there will always be the issue of scale. West Africa’s entire economy is about the same size as Switzerland’s. And there’s a bigger challenge. For the most part, these efforts to build the private sector are being led by people who don’t know much about the private sector—aid workers, World Bankers, government bureaucrats. They gravitate to politically-correct solutions, like small-scale technology, microfinance and cooperatives, rather than economically-efficient ones, like replacing subsistence agriculture with industrialized farming. And they are averse to the deregulation that enables free markets. The people who are in charge of helping developing nations are the ones least able (and predisposed) to do what it takes to help.

I found Jeniba in Kailahun—through Bockrie Sallu’s nephew (sadly, Bockrie passed away about 10 years ago). She and her husband Musa Konneh live in a small house consisting of a parlor with a bedroom on either side. The parlor was tiny and crowded. It held a single table with a solar-powered DVD player and two chairs facing a small sofa. The walls were plastered with pictures torn from magazines—soccer players, travel ads and Beyoncé. Wire mesh and shutters covered the windows. The doors were made of plywood as thin as cardboard. The Konnehs have no electricity or running water. The bathroom is an outhouse. Most Sierra Leoneans scrape their yards bare of grass as a precaution against snakes. But the Konnehs had a lawn in front with an orange tree and a hedge of decorative plants, which gave it a vaguely British feel, except for the glint of razor wire woven through the hedge to discourage thieves in the night.

After dinner, we discussed differences between Sierra Leone and America. I tried to avoid making comparisons that cast either in a bad light. My interpreter interrupted me, “You don’t understand, Sam, you don’t! Sometimes I don’t get paid for months. I live in a building where there are 50 of us and one toilet. If I want to use the bathroom, I have to go at four in the morning. I carry my bathwater in a bucket up four flights and make each bucket last two days. I cannot afford a light at night. I have a written agreement but that doesn’t matter. If the landlord wants to raise the price or make me leave, he does that. America is heaven. It is paradise. America is wonderful, I know that! I will find some job to do. Even cleaning floors.”

For those of us in the U.S., it’s hard to get our heads around how bad the lives of those in developing nations are. And how desperate they are. Desperate enough for college graduates to dream about jobs scrubbing floors. For someone who’s lived in a stinking tenement with no plumbing in a dangerous shantytown, an ICE detention camp is no big deal.

Poor nations are metastasizing sores that will eventually consume the better off. Aid hasn’t worked. Nor has containment. If two oceans and a desert aren’t enough to keep developing world problems out, it’s unlikely a beautiful wall will.

We don’t have a lot of time. Ebola is under control, but because of poor sanitation and sexual practices, the next HIV or Ebola may be just around the corner. Top military and police officials are quietly worried about another civil war. Sierra Leone has a lot of fault lines running under it—religion, race, gender, tribe, class, age. The one that ruptured was young vs. old, and it’s getting worse. Unemployment among youth is 70 percent. One international security consultant told me there were concerns that Boko Haram was getting a toehold in the country. The details vary, but each developing nation faces its own doomsday countdown.

Despite its dismal track record to date, many like Columbia professor Jeffrey Sachs, still insist the answer is aid; specifically, he calls for developed nations to dramatically up their aid commitment. I think that’s the wrong answer. The right answer has to be creating strong and robust private-sector based economies. Making those countries better places to live reduces the pressure to migrate, and creates the conditions for addressing other developing nation issues like the birth rate and pollution. And it can be done. But it’s not going to be done by aid workers or bureaucrats. The current U.S. administration has proved that businesspeople don’t know much about running a government. The inverse is true. Government people don’t know much about business. Part of Rwanda’s success has been because Kagame has sought out and embraced U.S. business leaders, like Jim Sinegal of Costco, Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase, and Howard Schultz, the Starbucks founder. As Paul Collier pointed out, the Marshall Plan was led by a businessman—not an academic or an aid agency.

But change will be a long time coming. As I was packing to leave, Jeniba pulled me to one side and asked me to take her to America. Instead, I did what the West has been doing for centuries. I pressed a hundred-dollar bill into her hand. I doubt that will help much.

→ Sam Hill is a Newsweek contributor, consultant and a best-selling author.