Wachira Kigotho

Africa’s tertiary education and research sector is not ready for global competitiveness and innovation as only 4% of new innovations on the continent are based on research and development, according to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa or ECA, the African Union and the African Development Bank. They propose drawing lessons from India.

In a key report, Innovation, Competitiveness and Regional Integration, the three top continental bodies conclude that most of Africa’s new innovations are driven by elementary practical experience and traditional knowledge skills.

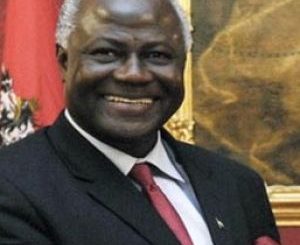

The report is the seventh edition of Assessing Regional Integration in Africa and was prepared under the leadership of Carlos Lopes, ECA’s executive secretary, African Union Commission Chair Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, and Akinwumi Adesina, president of the African Development Bank.

“So far, there is no strong evidence that science, technology and innovation policies in most African countries are adapted to country peculiarities or properly coordinated,” said Lopes.

According to the report, universities in Africa are producing graduates who are not well prepared for the workforce while laboratories are poorly equipped to produce top-notch cadres in science, technology, engineering and mathematics – STEM – disciplines.

The continental organisations recommended that African countries adapt India’s experience in developing policies designed to build a strong educational infrastructure able to increase skills and learning competencies – and should emulate India’s example in increasing spending on high quality tertiary education.

“Africa could draw lessons from India’s expansion of tertiary education, which generated a human capital base with highly developed STEM expertise,” said the report.

From rhetoric to practice

Towards this goal, the report is explicit that African science, technology and innovation policies should be pragmatic and pursue a phased approach to innovation and skills development.

“Decades of STEM disciplines policy rhetoric have not translated into increased science, technology and innovation capacity,” wrote Lopes, who coordinated the study.

At the launch of the report on 2 April in Addis Ababa, Tetteh Hormeku, head of programmes at the regional secretariat of the Third World Network, said there was need for Africa to follow India’s example of focusing on developing capacity and talent.

The report suggests that African countries explore the possibilities of establishing quality, publicly funded colleges and universities of higher and technical education, modelled on the Indian institutes of technology and of science, which are funded by the central government.

“These are some of the best examples of a public education system,” noted the report.

The central thesis is that Africa urgently needs to recognise the need for higher education reforms that will generate a high quality pool of graduates in STEM disciplines.

India’s experience suggests that African countries should encourage a bottom-up, location-specific approach to skills development, where the policy framework encourages innovations to meet local needs and local development priorities.

Africa could also draw lessons from India’s massive expansion of tertiary education, which generated a human capital base with highly developed STEM expertise that allows export of scientists and technologists.

Roping in the diaspora

According to the report, the Indian diaspora community is estimated to include about 25 million people across the world. The country has turned its global diaspora into a brain gain.

India’s diaspora is credited with some of the country’s high-tech successes through the India Centre for Migration, the Overseas Indian Facilitation Centre, the India Development Foundation of Overseas Indians and the Prime Minister’s Global Advisory Council that helps to identify some of the best Indian minds overseas.

Dr Charles Lufumpa, acting chief economist at the African Development Bank, said India had embraced science, technology and innovation as an instrument for driving economic growth.

That could be a starting point for Africa to realise the importance of linking science, research and innovation systems with economic agendas and the priorities of excellence and relevance.

“It is not too late for Africa to rope in its diaspora for development of high quality technical and research institutes,” said Lufumpa.

According to the report, the Indian diaspora’s contributions to science, technology and innovation have assisted in setting up several research hubs that include the Advanced Network Laboratory and IBM Research Centre at the Indian Institute of Technology in Delhi, the Bhupat and Jyoti Mehta School of Biosciences and Bio-engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology in Mumbai, and the Centre for Theoretical Physics at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore.

Learn from the ASEAN

Apart from learning from India, the authors stressed that Africa could also draw lessons from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations or ASEAN. Established in 1967, full members of the ASEAN are Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. Other members are Brunei, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia and Papua New Guinea.

While ASEAN’s main objective is to create a regional economic community, the bloc has also established regional science, technology, innovation and intellectual property cooperation.

Recently, ASEAN launched a plan of action to intensify research and development collaboration in strategic and enabling technologies, and to promote technology commercialisation among member countries.

Considering that the majority of ASEAN members are in a catch-up stage of development, the report argued that African countries could learn how Southeast Asian countries have been leap-frogging through the inflow and diffusion of technological skills and innovations, rather than by promoting purely homegrown technological advancement.

“Countries with a leap-frog policy will undertake more research and development initiatives, publish more, collaborate more and obtain more patents than countries seeking to catch up through the transfer of foreign technologies,” noted the report.

But no matter which route African countries take in their quest for development, the report continued, the key lay in how their tertiary education systems perform now and in future.

A pragmatic approach

Existing policies have not improved Africa’s science, technology and innovation performance.

African countries continue to perform poorly on major indicators that encompass tertiary education institutions – intellectual property, innovativeness and productivity as well as competitiveness.

The report concludes that the time has come for a pragmatic approach to science, technology and innovation – and the departure point is to avoid rhetoric and to recognise science and technology as the centrepiece in higher education.