Why are military coups going out of fashion in Africa?

CULLED FROM NEW AFRICA MAGAZINE

- REGINALD NTOMBA

- 11/11/2015

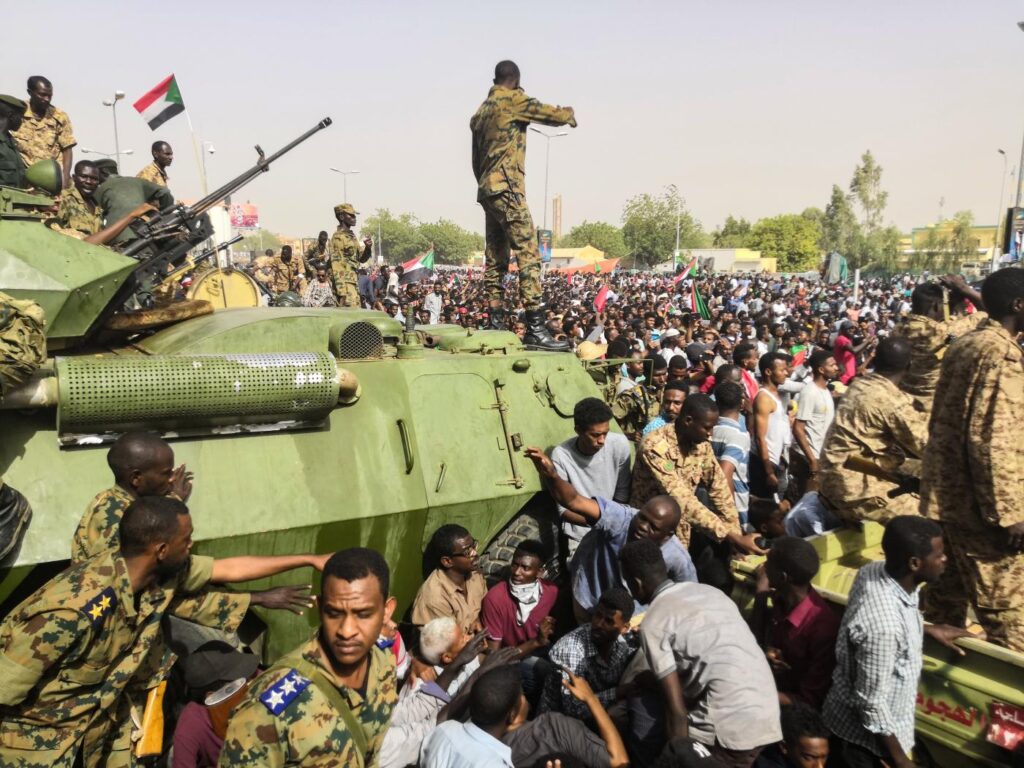

The euphoria of independence in Africa in the 1960s was quickly followed by a long succession of military coups until the late 1990s. The 2000s saw a comparative reduction but the military still routinely continued usurping political power through the barrel of the gun in some pockets of Africa.

But as democracy, good governance and economic growth – all part of Africa’s new narrative – take shape, the frequency and success of coups is clearly on the decline. Is this a harbinger of great things to come in Africa’s governance as the continent’s new breed of leaders work towards a unified continent, with the Agenda 2063 vision?

Research by the African Development Bank, among other institutions, shows that there have been more than 200 coups in Africa since the post-independence era of the 1960s, with 45% of them being successful and resulting in the displacement of the head of state and government officials, and/or the dissolution of previously existing constitutional structures.

In all three periods that the Bank’s research examined (1960-1969; 1970-1989; 1990-2012), West Africa came top for the number of coups, both successful and failed; Central and East Africa followed; while Southern Africa had the least.

Is Africa turning the corner?

The changing political landscape influenced by several governance reforms appears to be taking away the incentive for coups. It was believed a return to multiparty politics would forestall coups. At the height of the one-party state in 1980, one of Zambia’s freethinking politicians, Elias Chipimo, ran into trouble with the authorities when he opined that, “The multiparty system… [is] the surest way of avoiding coups and eliminating the disgraceful tendency of presidents ending up with bullets in their heads.”

Research, however, shows that coups continued across Africa well into the post-multiparty era. But in comparison, they declined under multiparty politics. Thus Chipimo’s prophecy was right, except its fulfilment would be gradual, not instant.

“The resurgence of military coups in Africa under the current wave of democracy may not be entirely surprising to those familiar with scholarly debates as to whether or not democratisation reduces the risks of military intervention in politics,” says Dr Shola Omotola, a visiting fellow at South Africa’s Wits University, in his assessment of the African Union’s promotion of democratic values. “Although not an entirely settled issue, studies have demonstrated that democracies that rank very highly in their legitimacy rating have better prospects of avoiding military interventions.”

Out of fashion: The Burundi and Burkina Faso coups

In May and September 2015, there were two unsuccessful coups attempts in Burundi and Burkina Faso, respectively. The circumstances were different but they could nonetheless represent a change in the times. In years gone by, when the throne was swept away, the fate of its former occupant was never in doubt. In worst-case scenarios, the deposed leader and his cohorts were immediately rounded up and summarily executed. It was unheard of for the military to seize power and hand it back within a few hours or days as happened in these two countries.

That could suggest that perhaps military coups are slowly going out of fashion and Africa may be finally turning the corner. Burundi’s President Pierre Nkurunziza and Burkina Faso’s interim leader Michael Kafando would do well to count their lucky stars and thank the change of outcome, while Godefroid Niyombare and Gilbert Diendere, the respective coup leaders, rue their failure.

So, what has changed?

First, the speed with which regional and continental bodies swiftly condemn and suspend from membership countries with coups has sent notice that such power grabs are no longer tolerated and that membership goes with certain standards and principles – and coups are not one of them. In the Africa of old, military dictators hung on to power for as long as they wished and received no censure from fellow leaders. But now groupings like SADC, ECOWAS and the African Union are loudly opposed to unconstitutional changes of government and those involved now know that they will be banned from the table of nations. At a time when countries are increasing cooperation through intergovernmental bodies, the effects of isolation are quickly felt.

“The OAU’s adherence to the principle of non-interference led to a reluctance to take effective action when coups d’état occurred. In principle, the OAU condemned violent coupsand the assassination of political leaders as unlawful under the OAU Charter,” argues Eki Yemisi Omorogbe in A Club of Incumbents? The African Union and Coups d’états. “In practice, however, the OAU usually accepted whichever government was in effective control of the territory and allowed that government to represent its state within the OAU.”

In contrast, the African Union in its Constitutive Act outlines broad principles on the promotion of democracy and good governance and outlaws unconstitutional changes of government, as does the African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance.

Democracy: The only game in town

Second, although democracy is still in its nascent stage in much of Africa, there is a consensus that it should be the only game in town. As such, any other means of ascending to power other than through elections is frowned upon and coup leaders risk isolation. In previous years when coups were in fashion, the military had no qualms about their actions. But today, it is worth noting that the first thing most coup leaders do upon seizing power is to call themselves a “transitional government/authority” and quickly promise a return to civilian rule within a short time. That in itself implies that the military are attuned to what the reputable mode of governance should be.

“The emergence of a growing culture of the rule of law, constitutionalism and the democratic dispensation has largely taken away the appetite for coups,” explained Anderson Chibwa, retired diplomat and lecturer at the Zambia Institute for Diplomacy and International Studies. “Also, four to five years is not a long time in the life of a nation. Within this period there are elections, though they may not be perfect. So those that want power can challenge for it through the ballot.”

Third, with a more liberalised political environment across Africa, public support for coups has generally waned. In the past, coups, illegal as they may be, were applauded by the masses as they were seen as the only means of removing sit-tight dictators who had shut all avenues for citizen participation in national affairs. But instead of cheering coup plotters like in the past, the people are now involved in campaigning for political parties and candidates of their choice to win power through elections.

Fourth, the vigour with which Africans resent external (read: Western) interference in their affairs means foreign interests that seek to divide the continent by sponsoring surrogates to violently seize power for their benefit will not have it easy any more. Besides, the Western world is itself preaching democracy on every street corner and so cannot afford to undermine its own gospel.

Fifth, agreeing on democracy and elections as a means of ascending to power means the governance question is largely settled. Therefore, the focus has shifted to addressing poverty, economic development and growth. What’s more, with the continent being dubbed the fastest growing, it is “Africa’s time” and Africa is preaching the “democratic dividend” – the benefits, such as increased investment and economic prosperity, that accrue to places with stable, democratic and credible government.

With several countries reaping the “democratic dividend”, those that want to disrupt their country’s growth trajectory through coups and acts of bad governance will not only find themselves out of fashion but also risk a revolt from their own people, who are witnessing what political stability and respect for the rule of law have achieved elsewhere on the continent and would similarly want to benefit from them.

There are many African leaders in office today who assumed power by force. As the continent moved towards democracy and multiparty politics, they smelt the coffee. They swapped their military fatigues for designer suits, and the bullet for the ballot. By holding elections in which they claimed landslide victories, they managed to launder and repackage themselves as democrats. How they initially got to power has ceased to be the issue and they have cemented their place at the continental table where they were welcomed on the overly generous assumption that they have reformed. But their governance style does not belie the cloth they were cut from. They still struggle to shed off the dictatorial streak and only talk “democracy” to appear in tune with the times. That is the legacy of coups that Africa is still contending with. That, too, is what partly holds back full democratisation, because leaders are operating in a changed environment but still stuck in the antics of the past.

As the continent hopefully says goodbye to coups, it is hoped that the over-staying leaders in some pockets of the continent, including those who came to power through coups, will be the last of such pseudo- democrats to grace Africa’s post-independence political landscape, as a new era of African political governance clearly beckons.