By Moses A. Kargbo

Anti-FGM (Female Genital Mutilation) campaigners were highly hopeful that the end was in sight in their struggle to have the practice outlawed following its temporal ban by the Sierra Leone government as part of measures to curb the spread of the virulent Ebola virus disease; but little did they realise that this would only be short-lived, and that once the disease is successfully brought to an end, people can go back to business as usual.

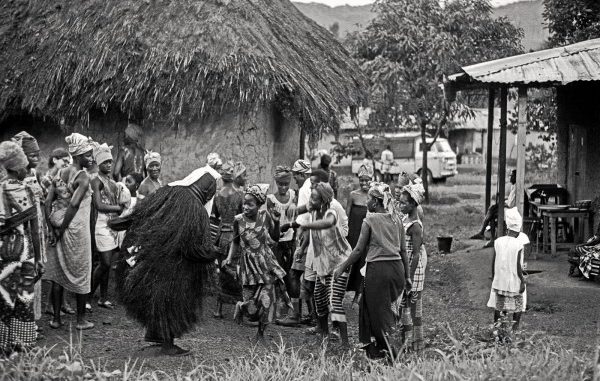

Sierra Leone is one of 28 countries in Africa where FGM is still being practiced. While most countries in the continent do not normally participate in the secret female ritual, the practice is still popular in Sierra Leone. The reason advanced by some FGM protagonists is that the Bondo society (as commonly known in the country) helps “young women earn the rites of passage into adulthood”. Whether that has proven to be the case over the years is open to debate, especially with the wild behaviour of some of our young girls, majority of whom had themselves gone through these initiation rites.

The Soweis, who hold the most senior rank in the Bondo society, have always frown at attempts to force them to abandon the practice, seeing it as a direct attack not only on their culture and womanhood generally, but also on their survival. The practice exists in every village and town across Sierra Leone and this, to a large extent, has the tacit endorsement of politicians (who sometimes pay the fees for the initiation rites) and the local authorities. So abolishing the practice appears to be a taboo for the political elite, as initiation ceremonies especially in rural communities could be used as platforms to canvass for votes during election campaign periods.

It could be recalled that Paramount Chiefs representing all 149 chiefdoms in the country had insisted that a ban on FGM be removed from the Child Rights Act in 2007. Such are the influence and power wield by protagonists of the practice that in July this year, when a rumour circulated that the government was going to ban FGM, women in the public gallery in the Sierra Leone Parliament threatened to walk out. Furthermore, hostility towards opponents of the practice was underlined in 2009 when four female journalists in the eastern city of Kenema were forced to strip before being frogmarched through the streets because they were alleged to have spoken unfavourably on radio against FGM.

Secret societies are ancient cultural institutions that play a major role in West Africa and have existed for hundreds of years. Women who are members of the Bondo are regarded as having a higher standing than other women. Roughly three million girls in Africa undergo FGM every single year and Sierra Leone is one of the only countries in West Africa where the rate of prevalence is over 90%, according to a 2013 report by Owolabi Bjälkander titled: “Female Genital Mutilation in Sierra Leone: Forms, Reliability of Reported Status, and Accuracy of Related Demographic and Health Survey Questions.”

In opposition of the arguments of supporters of the practice, anti-FGM advocates highlight the negative side of FGM, stating that more than 80% of women reported suffering a minimum of one health complication after being circumcised. People against it widely refer to it as mutilation, which is a controversial term that is rejected by members of communities who practice it. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has adopted this term and it is widely used to describe the injury made to the women’s genitalia even though the intent was not to mutilate.

The Amazonian Initiative Movement is one of several non-governmental organisations in West Africa against FGM. The aim of the group is to educate women who perform the practice and set them up with another job besides performing this procedure. WHO has consistently condemned this traditional practice as “willful damage to healthy organs for non-therapeutic reasons”, and they have warned that the practice of female genital mutilation can result in infertility, pregnancy and childbirth complications, and psychological problems through inability to experience sexual pleasure. Supporters against the eradication of FGM believe it violates the human right to bodily integrity. However, Sierra Leone does not have an explicit law against the practice of FGM.

The country recently ratified the Maputo protocol, an African charter of women’s rights agreed in 2003 that calls for the elimination of harmful practices, including FGM. In response to this, the Minister of Social Welfare, Gender and Children’s Affairs, Alhaji Moijueh Kaikai, indicated in a statement in July that the Cabinet had discussed outlawing FGM for girls under 18 years. A draft strategy paper has been compiled by academic Bjälkander, with input from district Soweis, the Family Support Unit of the Sierra Leone Police, and Minister Kaikai himself.

FGM practice saw a drastic decline in Sierra Leone as a result of the Ebola crisis, which bedevilled the country for 18 months. Activists against FGM had tried to capitalise on the lull during the Ebola crisis to end the practice permanently but this is yet to get the support of the political class, who many Sierra Leoneans are less enthused will ever support a permanent ban on the practice “for political reasons”.

President of the National Council of Soweis in Sierra Leone, Mammy Koloneh, said she would prefer to keep the tradition going as it has been part of Sierra Leone’s culture for generations, and it would be wrong to stop it.

It is for such a position held by Koloneh and many other influential traditional and political individuals that outlawing the ancient traditional practice will continue to remain a very tall order. Ebola has ended, meaning the temporal ban on FGM may have to be lifted after the 90 days grace period set out by the government to continue to observe the victory over the dreaded Ebola virus. In effect, FGM is still very much part of our traditional practice until such a time when the government of Sierra Leone will heed to the call by the UN General Assembly in 2012 for countries to proscribe all harmful practices.

But there is still a ray of hope for anti-FGM campaigners as summed up by Bjälkander: “The fact that some communities have chosen not to practice FGM during the [Ebola] crisis together with evidence on the effect and impact these bans have had on FGM could be valuable for developing interventions for total abandonment of the practice.”