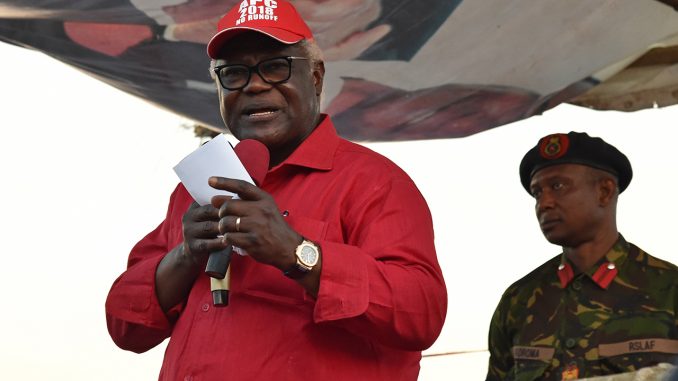

Sierra Leone’s outgoing President Ernest Bai Koroma delivers a speech during a campaign rally for his party’s presidential candidate on March 3, 2018, in Kambia, ahead of the country’s general election.<br />Sierra Leone goes to the polls on March 7 for a general election that will select a new president, parliament and local councils.<br />/ AFP PHOTO / ISSOUF SANOGO

Over the last two decades, it has been the best of times in the Sierra Leonean capital of Freetown, and the worst of times in the Liberian capital of Monrovia. Both capitals – where much of the population of West Africa’s tragic twins live – have symbolized contrasting fortunes.While devastating civil wars broke out in the two countries by 1991 – killing an estimated 250,000 people in Liberia and 70,000 in Sierra Leone, before being stemmed by Nigerian-led regional peacekeepers – Sierra Leone’s civil war ended in 2002, and the country is headed for its fourth democratic election on 7 March.

Liberia’s civil war was, however, reignited in 2001 under warlord-turned-president, Charles Taylor, eventually ending only with Taylor’s exit into Nigerian exile two years later.

Most former combatants have, however, not been provided employment, leading to fears of future instability. Johnson-Sirleaf’s government was also accused of corruption and nepotism.

Though controversially awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011 – a few days before presidential elections – and though adored by infatuated Western donors, her reputation in Liberia and West Africa is much more negative.

The real mystery is, however, why neighbouring diamond-rich Sierra Leone remained stable 12 years after UN peacekeepers left the country, and 16 years after the end of a devastating 11-year civil war. Though the world body had spent $5 billion in Sierra Leone over six years, much of this went towards its peacekeeping mission rather than to rebuild the shattered country.

Considering that many of the same conditions existed in post-war Sierra Leone as existed in Liberia – massive youth unemployment; poor governance and corruption; regional and ethnic divisions; and 70 percent of the population living in poverty – what factors explain the reasons why Sierra Leone did not slide back into conflict?

One crucial but often overlooked source of Sierra Leone’s stability has been its active civil society sector.

Sierra Leone’s associational life has historically also included long-standing church groups, Islamic fraternities, initiation societies, sports clubs, and credit clubs which have all demonstrated impressive resilience and resourcefulness in holding society together.

One sector that post-war governments in Freetown prioritised was the critical area of education, with 20% of expenditure going to this sector by 2006. As Sierra Leonean scholar, Ismail Rashid, also insightfully noted, while there has been widespread youth unemployment in post-war Sierra Leone, there has not been large-scale youth destitution.

The country’s youths have been resourceful at engaging in such activities as petty trading, street-hawking, and driving okada taxis.

Despite these positive developments, governmental corruption, has, however, remained rife, and politicians have periodically fanned ethnic divisions.

A plethora of international actors were involved in assisting Sierra Leone’s peacebuilding efforts. Led by the UN, these donors also included the African Development Bank, the World Bank, and Western governments.

Though the support provided by these partners was useful in keeping the fragile peace, the amounts provided were often derisory and clearly insufficient for transforming Sierra Leone’s institutions in ways that could ensure sustainable peace. The rhetoric of external donors has always been more impressive than their provision of resources.

For both Sierra Leone and Liberia to remain stable, serious financial support will need to be provided by regional and external actors to enable domestic actors to transform rather than merely stabilize their still fragile states.

Professor Adekeye Adebajo is Director of the Institute for Pan-African Thought and Conversation at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa.

THE NIGERIAN GUARDIAN NEWSPAPER