By Solomon Ayele (PhD)

With the return of big power competition in a multipolar world, the challenge that Africa faces in 2019 and beyond is a combination of a new and more dangerous Cold War and the Scramble for Africa, writes Solomon Ayele (PhD), founder of Amani Africa Media & Research Services, a pan-African policy research, consulting and training think tank operating from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Writing in the March 1983 edition of the New York Timesunder the intriguing headline of “Africa: From Cold War to Cold Shoulders” John Holmes summed up aptly the treatment the continent endured in the hands of foreign interveners.

“Having been carved up and colonised by European powers and turned into pawns, knights and rooks on a cold war chessboard by the superpowers, Africa now faces a devastating new problem: indifference,” he wrote.

Indeed, there was a moment in the post-Cold War period, which was marked by America’s almost uncontested hegemony, during which Africa was left to its own devices.

“Africa was left to fend for itself,” as Kofi Annan, the late former secretary-general of the United Nations, put it in 1998.

Indeed, Africa rose to the challenge. It turned the misfortune of being what Holmes called “a devastating problem,” of being treated with indifference, into a useful policy space for exercising its self-determination by charting a socio-economic and political path it deemed fit. It was during that period and in the course of exercising its agency that Africa found its voice.

The outcome was the transformation of the OAU into the African Union, leading to the establishment of a higher level of integrationist pan-African organization with an ambitious but necessary peace and security order. This was also a period during which the ground for the economic boom of the continent was laid down.

But “the devastating new problem” was short-lived. With changes in the pattern of global power relations, it lasted not more than a decade. With emerging powers, led by China, expanding their international reach and engagement, the first decade of the 21st century witnessed the next cycle in the intervention of global actors on the continent.

This is a period dubbed by some as the new scramble for Africa. As in the first scramble, the dynamics of this new one lies outside Africa in the changing global power shifts. It coincided with the transition from the unipolar world system of the immediate post-cold war period to the plurality of centres of power.

As a 2010 article on ChinaDailyobserved, the rise of China marks “the start of [a] multipolar century, in which, along with US, Japan, Russia, and [the] EU, China will play an important role.”

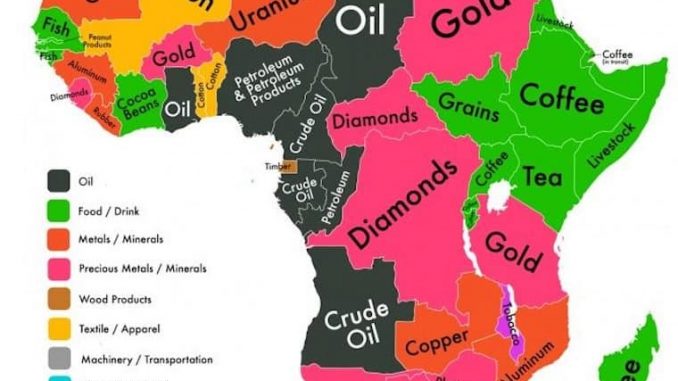

While the first Scramble for Africa, which took place between 1881 and 1914, arbitrarily carved up the continent into the colonies of the major European powers of the late 19th century and subjected its peoples and resources to foreign oppression and plundering, the new scramble aims at strategic resources such as oil and minerals.

Instead of military force, the means used in the first Scramble for Africa, the main means used in the new scramble are financial and economic instruments of aid, trade, loans and investments supplemented by security relationships.

Fuelled by rising demand of the economies of the emerging powers, particularly China, the new scramble for Africa has changed the political economy of the continent and its trade and economic relations.

China outpaced the US to become the continent’s largest trading partner in 2009. Its investment on the continent also more than doubled in the half decade beginning in 2011 to 40 billion dollars.

With the ongoing shift from the use of fossil fuels to electricity as sources of energy, including for fueling cars, and the major technological advances that rely on strategic minerals such as Coltan, the engagement of external powers on the continent has continued to witness major expansion.

Within the framework of the AU as well, in the four years to 2008, a series of partnerships were initiated and launched. These included the Africa-South America, Africa-India and Africa-Turkey. At the same time, partnership forums that were already in existence between Africa and its traditional partners and which were being regulated by cooperation frameworks were redefined, invigorated and strengthened.

Apart from the Africa-China Forum (FOCAC), these newly redefined partnerships include Africa-Europe Partnership, Franco-African Summit, Africa-United States relationship under AGOA, the Africa-Japan (TICAD), and Africa-Asia Sub-regional Organizations Conference (AASROC).

Countries in the Middle East and Gulf have also joined the scramble for Africa. For example, the UAE invested an estimated 11 billion dollars in capital in Africa in 2016, the second largest in the world after China. The trade and investment portfolio of other countries such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia has also witnessed major increases, particularly in the aftermath of the 2007/8 global financial crisis.

The new scramble for Africa is not confined to the economic sphere only. It also involves competing models of political systems and development. While China presents autocratic and technocratic forms of political and economic development models with heavy state role as viable options for developing countries, the continent’s traditional partners advocate democracy and private capital based model of political governance and economic development.

Another form that the new scramble has taken involves the militarisation of various parts of the continent. Although prompted by the war on terror, the US established the Africa Command and expanded its military presence on the continent with a constellation of bases including 34 sites scattered in many parts of the continent.

China, an increasingly dominant actor on the continent, has added a growing security dimension to its rising presence on the continent. It established its first foreign military base in Djibouti in 2017.

It also deployed troops including combat forces to UN peacekeeping missions in South Sudan and Mali. Beyond bases and blue helmets, China’s security engagement also involves growing defense and security relations with African countries. Russia has initiated security alliance in the Central African Republic and is in the process of securing logistics base in Eritrea and a military base in Sudan.

The scramble for the control of the sea-lane along the Horn of Africa coast has also increased. The UAE has established a presence in Eritrea and Somaliland. Saudi also finalised a deal for establishing a military base in Djibouti, while Qatar signed a four-billion-dollar deal to manage a Red Sea port with Sudan in March 2018.

Is this big power competition a new but more dangerous Cold War?

As the new scramble seems to be deepening, a major shift in the nature of international engagement has been introduced during 2017/2018. Before Africa has been able to develop effective strategies for coping with the new scramble, in the new year of 2019 and the years to come it is faced with the challenge of becoming a theatre for big power competition.

During the 19th Chinese Communist Party Congress in 2017, President Xi Jinping announced China should become a nation with pioneering global influence by 2050. Russia, another resurgent power, has in recent years employed a strategy manifesting what the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace termed “the return of global Russia.”

Indeed, its role in Eastern Europe and the Middle East shows that Russia is displaying a show of force to assert itself as a global power. But as the Carnegie Endowment pointed out, Russia has engaged in a broad, sophisticated, well-resourced, and – to many observers – surprisingly effective campaign to expand its global reach.

In early 2018 while unveiling the National Defense Strategy of the US, former Defense Secretary James Mattis announced that great power competition – not terrorism – is now the primary focus of US national strategy. As reported, the National Defense Strategy states that “long-term strategic competitions with China and Russia” are the “principle priorities” for the Defense Department.

This proclaimed orientation and content of the new defense strategy herald the return of big power competition as the major feature of international relations. It inaugurates a new era marking the end of a period in which the different centres of power sought some form of, albeit ad hoc, accommodation and the beginning of a period in which they are poised to pursue antagonistic rivalry for hegemonic dominance and supremacy.

“The empirical reality makes it abundantly clear that relations between the major powers have become more tense and potentially more dangerous than they have been since the end of the Cold War,” as Tekeda Alemu (PhD), a well-respected senior Ethiopian diplomat who recently retired, wrote recently. Quoting the Secretary-General of the UN, he further argued that “the current situation is even more dangerous, because it is less regulated and managed, thus becoming more susceptible to reaching the tipping point beyond which is unthinkable.”

That Africa is one of the main theatres for such competition became evident when the “new Africa strategy” of the US was launched in December 2018. While unveiling the strategy, National Security Adviser John Bolton pointed out that the greatest threat for US interests came not from poverty or Islamist extremism but from China and Russia.

Highlighting the centrality of big power competition in the US’s Africa strategy, the New York Times published an article headlined “Bolton outlines a strategy for Africa that’s really about countering China” and the editorial board of the Financial Timesdubbed the strategy as “America’s scrambled approach to Africa.”

In this context, the risk that the continent faces is to have the same fate it had during the Cold War.

To borrow from Holmes, this is the fate of being “turned into pawns, knights and rooks on a cold war chessboard by the superpowers.” As the Financial Timespointed out, ‘[i]f his (Bolton’s) speech on Friday is the guide, Washington’s take on Africa is stuck somewhere between the 19th century Scramble and the Cold War.”

It is interesting to note that in announcing the strategy, Bolton was forthcoming in indicating what the US expects of African countries.

Commenting on the matter, Tekeda observed “[a]s recent pronouncements have made clear, Africa is on the verge of being in the vortex of this rivalry.” He warned African countries that ‘[t]he crude formulation of the demand made by the major powers in terms of being “either with us or against us,” which was witnessed occasionally in the past, might confront countries such as Ethiopia in a very challenging manner.”

At a time of rising and unregulated big power antagonism and rivalry, the willingness of and minimum consensus among major powers to defend and operate within the framework of multilateralism is also fading. In this context, troubling signs of regional tensions descending into major conflicts – in to which major powers are sapped leading to the breakdown of world order – have been witnessed as the cases of Syria, Yemen and Ukraine show.

It is clear that the challenge for Africa during 2019 and beyond is how to forestall the emergence of such a scenario in any of the existing or emerging hot spots. Indeed, the impact of this new context, if not guarded against, could be very dire for the continent.

As Tekeda pointed out ‘[w]hatever small hope might still be left for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda and the achievement of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, will be thrown out the window if Africa allows the region to be a platform for the rivalry between the major powers that morphs into military activities[,] which are manifested in a variety of ways, including through proxies.”

It is evident from the foregoing that big power rivalry is becoming a major factor shaping international engagement on the continent in 2019 and beyond.

As rightly pointed out, “Africa is entering a period when its ability, readiness and resolve to act in the interest of the people of the content is going to be tested.”

Indeed, there may not be more challenging time than this that puts to unprecedented test the leadership of African elites and the efficacy and value of the peace and security mechanisms developed under the African Union.

The task for leading countries on the continent is “to ensure that developments in their region do not become a catalyst for great power rivalry leading to military confrontation.”

It is imperative that African actors, notably the African Union and major countries on the continent, identify those parts of the continent particularly vulnerable to the consequences of such rivalries – such as the Horn of Africa as specifically cited by Bolton – and develop a common African approach and mitigating strategies to shield regional or country situations from becoming sites of major power rivalry that precipitate the destruction of societies and breakdown of world order witnessed in Syria and Yemen.

Africa and the AU should also defend and rely on, as useful arsenal in shielding the continent, the regional multilateral framework anchored on the norms and processes of the African Peace and Security Architecture. An equally critical component of the strategy must be the commitment and mobilisation of countries of the continent and the AU to use existing partnership frameworks for supporting and defending multilateralism within the framework of the UN.