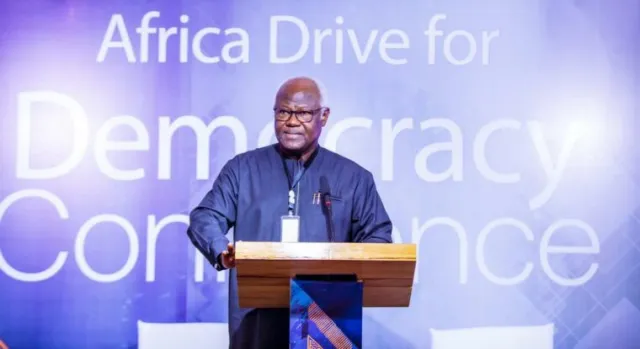

Ex-President Ernest Bai Koroma has delivered the keynote address at the ongoing Drive For Africa’s Democracy Confrerence in Arusha , Tanzania. Newspapers in East Africa are carrying screaming headlines about the former President’s speech, in which he lashed African leaders who want to illegally cling to power by sabotaging the constitution.

HERE IS THE FULL STATEMENT

Distinguished ladies and gentlemen, good morning (Habari az asubuhi).I am pleased to be in this beautiful land of natural attractions, the land of the majestic Mount Kilimanjaro. It is also gratifying to be associated with this inspiring mix of champions of democracy, good governance and the rule of law.

I appreciate this honour to deliver the keynote at this very auspicious Drive for Africa’s Democracy Conference. Hei/shima to the Centre for Strategic Litigation, to the MS Training Centre for Development and Cooperation, and to the Institute for Security Studies, for creating this wonderful platform.

The theme, ‘Fighting the democratic backslide through renewed action and solidarity’, could not have been more apt and timelier. This is definitely a worrying trend that should be of utmost concern to anyone who professes to be a democrat. And yes, reversing the decline in African democracy has become the preoccupation of many associations, institutions and like-minded leaders like you!

Let me begin by providing some reflections on how we found ourselves in this problem, and then put in context the journey of democracy on the continent. In the post-independence era, the governance trend in Africa was the one-party system, which was justified by some of the leaders who emerged, as the basis for uniting diverse ethno-regional, linguistic, political and religious groups. The argument was that colonialism destroyed African values, traditions, customs and its unitary system of governing which kept African nations together, with economically viable societies.

While I would not go into the merits or demerits of that claim, allow me to say that after more than six decades of independence, we could have done better in managing our affairs. Otherwise, the post-independence public opposition to what had turned out to be authoritarian regimes would not have arisen. But it did, due to the steady accumulation of discontent over economic hardships and deepening social divisions along ethno-regional, religious, and class systems.

This was compounded by the marginalisation of the continent’s youth and women. With them being denied their voices, identities, recognitions, and the place they deserved in their societies; they became disenchanted and their frustration bred grievances between states and their citizens.

Amid that crisis of legitimacy within African states, a combination of internal and external factors, some noted earlier, created effective pressure for political change culminating in the introduction of multiparty elections in most African countries in the 1990s. This was especially after the structural adjustment policies supported by international financial institutions failed to usher in the much-anticipated economic recovery, growth, and prosperity.

While all of this was happening on the continent, a democratic revolution was sweeping through the world; shining a light on the protection and promotion of human rights. That light beamed on Africa and provided an impetus to independent and public- serving Civil Society Organisations, (CSOs) which were effective in apprising the citizenry of their fundamental rights and responsibilities; in explaining the role of the government and state institutions, as well as the responsibilities of state functionaries.

Also, around this time, international partners had started tagging external financial supports to good governance in order to further strengthen the demands for transparency and accountability. Since then, democracy, understood as institutionalized, time-bound and competitive elections, along with respect for civil and political liberties, became integral to the agenda of many countries. And, until recent times, it flourished in much of the continent.

In my country Sierra Leone, since 1996, we have had five peaceful, free and credible elections in which opposition parties have won twice. But democracy in Africa should go beyond regular elections. Essentially it should be about good governance, about safeguarding human rights and the rule of law, about giving hope to the citizens through tangible deliverables particularly on the economy, in access to social infrastructure, services, or in peace consolidation.

After all, democratic good governance is a matter of leadership with a vision, compassion, and a commitment to positively impact the lives of the citizenry. And if you are in it to serve, you must be strong enough to stay focused, and to resist the cheerleaders who would want to declare you as the only one capable of leading the nation.

The fact is, democrats and autocrats emerge out of the character of the individual. You are elected for a limited time; your responsibility is to do your best within that timeframe. It should never be lost on elected officials that at the end of their tenure, they must step down and walk away in peace and in harmony.

Democratic good governance mostly thrives in settings where there is a collective approach to leadership, with those leaderships willing to leave their footprints on the sands of time where there is an inter-generational approach to building a better and brighter future.

I was elected president of the Republic of Sierra Leone in 2007; few years after my predecessor had ended our country’s very brutal 11-year civil war. Throughout those depressing years, I was in the country even though I had the means to have left. So I witnessed firsthand the horrors, the pains, and the devastation brought about by the war. Roads, water, and electricity infrastructure were completely destroyed. Schools, hospitals, and government institutions were similarly comprehensively wrecked. In such a situation, everything was a priority including the building of the fragile peace that existed. In fact, there was justifiable fear that the country could easily relapse into violence.

I was, therefore, very clear in setting the right tone for the building and consolidation of peace and democracy, knowing that my government did not have the luxury of time, financial resources, nor the human resource to resolve all the problems in five years or even ten. But I was determined that we could make substantial progress if we had our priorities right.

We, therefore, developed what we called the ‘Agenda for Change’, by which we set ourselves five key priorities with clear deliverables and timelines, drawing from my over 30 years private sector experience. These ideas could not have been implemented in a chaotic political transition.

The first step was to send the right message for a smooth transition and peace consolidation. I drove to the outgoing president. Drove to the VP, ordered his security detail back. Assured him of his safety stay at the official residence until. Announced that outgoing cabinet ministers and other senior government functionaries should stay until the new appointees were sworn in, A comprehensive and peaceful handing over was completed. Those actions were so reassuring. Fleeing officials returned. First cabinet with past ministers. We had a peaceful handing over, Delegation of first trip out of the country.

On the governance side, we reviewed policies, acts, and formulated new ones, all in a bid to open the space for political, public and civil society participation. Adopted OGI – Town hall meetings – public participation in public policy formulation, programmes, projects and their feedback on the implementation process.

On the fight against corruption, The Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) Act was given prosecutorial powers and autonomy. Sitting government ministers accused of corruption stepped aside until their investigation was completed. Those who were found guilty faced the consequences.

These actions paid off in many ways. First, we had a very smooth transition which had a positive impact on governance and peace. We restored hope and built public trust in the government. We also earned the confidence of the international partners and investors. Our rankings improved dramatically in Doing Business.

In fact, in 2010, the World Bank ranked us among the ten most reformed countries in the world. We also recorded more improvements on the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Mo Ibrahim, Transparency International, and Freedom House indices. In turn, we attracted considerable financial supports and foreign direct investments which we invested in building roads, hospitals, schools, markets, support farmers with machineries and fertilizers, and also access to finance.

We increased public sector conditions of service and the minimum wage; and restored pipe-borne water and electricity to many parts of the country, most which had not seen running water or electricity for over 30 years. Many parts of the country where people were spending days to travel to were now being accessed within hours. This hard work won the hearts of Sierra Leoneans, which made me win the election for a second term mandate on the first ballot.

To a large extent, I maintained the same approach during my second term to the point that in 2013, the World Bank rated Sierra Leone as the fasted growing economy in Africa. However, that achievement was reversed by the outbreak of the deadly Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in 2014. The drop in the prices in the World Market of commodities such as iron ore, which was then the mainstay of our economy, compounded the problem.

Nonetheless, the work I did as president gained me considerable popularity, and there were calls for me to run for a third term, which would have meant that I had to change the constitution, to hang on to power. I was not confused by those calls, as I knew that I had enjoyed a great privilege and blessing to have led my people for ten years, and that it was time to leave.

It is important to note that as a leader, people will provide all sorts of advice, but it is your business to analyse them, and make the right decision. Changing a constitution to run for a third term is simply undemocratic and should be discouraged across the continent.

Knowing and embracing my limits, we had elections organised, and I graciously handed over power and went to my home town in retirement. By the time I left office, Sierra Leone was rated the most peaceful country in West Africa and the third most peaceful in Africa by the Global Peace Index. Before that, the then UN Secretary–General Ban Ki-Moon had described Sierra Leone as a storehouse of post conflict reconstruction and peace building. To this day, wherever I go, citizens would show up in large numbers to thank and pray for me. There could be nothing more fulfilling than serving your people well.

As you can see, there is very good life after the presidency too. Not only that I am being celebrated by my compatriots, I am also still having these and other international engagements to attend and contribute to. At the same time, I do sleep better; spend more quality time with my family, my grandchild, and hangout with my childhood friends.

Unfortunately, the current trend across Africa represents a considerable threat to peace and democracy. Right under our watch, democracy is being hijacked, re-engineered, and re-presented in ways that the public could no longer recognize.

In effect, once again, the anticipated democratic dividend of a good life – through the effective management of national resources – of equal access to such resources; of access to justice, to social services, to participate inclusively in the governance of the state; that democratic dividend which should guarantee freedom of speech, of association, of assembly and even of peaceful protest – irrespective of the individual’s political, social, religious, ethnic or regional affiliations – is increasingly being reneged upon by the political class.

Africa is experiencing a resurgence of the monster of state capture of not only national institutions of governance; but sadly also, of civil society and the media. In other words, rather than building and nurturing strong democratic institutions as President Obama once implored, we are getting democratic strong men who married to the ignominy of the third term.

Democracy is being overthrown not necessarily through the barrel of the gun, rather, through the ballot box, aided and abated by the very institutions which ought to protect it. Even worse, administrations borne out of such democratic coup d’états have failed to learn from the hazards of the one-party bad governance system. In fact, they have evolved to become squanderers of the democratic dividend. State security apparatus are increasingly being used to harass, intimidate, and detain opposition leaders and their supporters; persecute predecessors and officials of the past governments.

We are also witnessing Parliaments working in cohort with the executive in some countries, to manipulate the constitution and pass laws that are designed to entrench the powers of the executive. At the same time, the judiciary, which is supposed to hold the balance between the opposition, the public and the government, has been instrumentalised to the advantage of the political elites, against opposition parties, and those with critical views.

Elections management bodies whose responsibility it is to impartially and fairly conduct free, credible and widely acceptable elections, are instead doing the bidding of the ruling parties.

The professed fight against corruption is only as potent against the opposition as it is protective of the status quo. These factors have not only discouraged young people on the continent, but they are contributing to the rise in activities of violent extremist groups, and violent eruptions between the state and its citizens. Violent extremist groups have thrived in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin as a result of the fact that there is a ready-made army of young people, disconnected from the state, and denied socio-economic opportunities, who are willing to join those groups. In some states, we see the emergence of gangs and cliques, also a demonstration of young people socialising with violence, as a means of social expression, and their search for recognition.

Such reversal of democracy has deepened public disaffection while the economic consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic, climate change and now the Russian –Ukraine war; have compounded the problem. Apparently, owing to the way they have entrenched themselves, massive civil unrests and/or military strongmen tend to be the recurring means by which democratic strongmen could be removed from power.

As democrats, the ideal situation is that political change should always happen through constitutional means because violent change of governments often results in loss of innocent lives. It also brings about a wide range of social, political and economic consequences. But as we have seen, the reality is quite different.

West Africa alone has recorded three military takeovers this year in Mali, Burkina Faso, and in Guinea. There have also been two attempted coups in Niger and Guinea–Bissau. Coups and insurrections have occurred in other parts of Africa as we have seen in Sudan, and Algeria. Even the stubborn violent insurgents in the Sahel and Maghreb regions have their roots in factors including the resurgence of bad governance.

Freedom House recently reported that out of 54 countries in Africa, only 12 could be considered as ‘free’ over the last 15 years while only 7% of the continent’s population live in such societies.

The democratic reversal is indeed serious that it has alerted ever many organisations and groups to the threats it portends for the economic growth, peace, security and stability of our beleaguered continent. This is why we are here – to explore how, in solidarity, we could strengthen the ‘Drive for Democracy’. Be assured that you are not alone.

The African Union (AU) and its Regional Economic Communities and Mechanisms, such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), have even embarked upon a comprehensive review of their Governance, Peace and Security protocols with clear deliverables and timelines. The African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) and the Coalition of Democratic Association (CoDA), both affiliates of the AU, are all actively involved in efforts to stem this decline.

The new thinking is that monitoring and observation should go beyond elections to include governance, so that where violations are occurring, early warnings could be signaled. Additionally, discussions are ongoing on how to enhance the effectiveness of responses to constitutional violations. I am also involved with other initiatives such as the West African Elders Forum (WAEF) and the Obasanjo Presidential Library, all gearing towards addressing the situation in the ECOWAS region.

We must pile this pressure with undiminishing intensity until it becomes extremely untenable for anyone to derail the democratization process that Africa embarked on in the 1990s. The good news is that there is still reason to be optimistic. A survey conducted by Afrobarometer in 30 countries shows that majority of Africans prefer democracy as a political system over and above autocratic ones.

That aspiration could not be realized without the decisive intervention of civil society organisations. And here is the reason: democracy without a vibrant, independent and public–centered civil society is like a person with a weak immune system. As a strong and healthy immune system is to the human body, so are CSOs to the democratic state. They play the critical role of ensuring that the system remains healthy and functional. They hold the balance between the government and the citizenry and they should do so by drawing the attention of the government to lapses; issues of corruption and other governance inefficiencies.

A listening government should respond by taking remedial actions but if they don’t, the CSOs should be strong enough to call out the authorities fairly and in a professional way. Also, civil society must endeavour to fully grasp government policies, programmes and projects so that when they make interventions, they do so from a position of knowledge.

Now this is important because with the facts, even the government would find it difficult to disagree with them. At the same time, the public and even international partners would benefit from their independent insight. That way, they escape the all too familiar accusation that they are working with the opposition or the public seeing them as an extension of the government. What also cements civil society’s credibility is avoiding being seen as agents of regime change. It is a difficult balancing act but it is doable.

Over the years youth-led social movements in countries such as Senegal and Burkina Faso, have been very effective in mobilsing their peers and contending with the state on critical issues, thereby fostering changes that they wanted to see. Such examples point at the fact the power is in the hands of the people, and leaders can only be as powerful as their people perceive them to be.

In concluding, I would like to profoundly commend the organisers for bringing all of us together to reflect on a very critical issue. I also would like to thank them for the efficiency with which they organised the logistics that enabled all of us to be here. Ladies and gentlemen, I think the organisers deserve a loud applause! Asante Sana and I wish you fruitful deliberations!