When Charles G. Taylor tied bed sheets together to escape from a second-floor window at the Plymouth House of Correction on Sept. 15, 1985, he was more than a fugitive trying to avoid extradition. He was a sought-after source for American intelligence.

When Charles G. Taylor tied bed sheets together to escape from a second-floor window at the Plymouth House of Correction on Sept. 15, 1985, he was more than a fugitive trying to avoid extradition. He was a sought-after source for American intelligence.

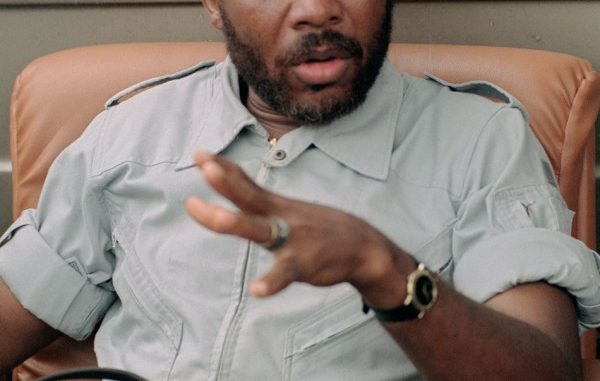

After a quarter-century of silence, the US government has confirmed what has long been rumored: Taylor, who would become president of Liberia and the first African leader tried for war crimes, worked with US spy agencies during his rise as one of the world’s most notorious dictators.

The disclosure on the former president comes in response to a request filed by the Globe six years ago under the Freedom of Information Act. The Defense Intelligence Agency, the Pentagon’s spy arm, confirmed its agents and CIA agents worked with Taylor beginning in the early 1980s.

“They may have stuck with him longer than they should have but maybe he was providing something useful,’’ said Douglas Farah, a senior fellow at the International Assessment and Strategy Center in Washington and an authority on Taylor’s reign and the guns-for-diamonds trade that was a base of his power.

The Defense Intelligence Agency refused to reveal any details about the relationship, saying doing so would harm national security.

Taylor, 63, pleaded innocent in 2009 to multiple counts of murder, rape, attacking civilians, and deploying child soldiers during a civil war in neighboring Sierra Leone while he was president of Liberia from 1997 to 2003. After a proceeding that lasted several years, the three-judge panel of the UN Special Court for Sierra Leone is now reviewing tens of thousands of pages of evidence, including the testimony of about 100 victims, former rebels, and Taylor himself, whose testimony lasted seven months.

“We hope the verdict will come in the first quarter of this year,’’ said Solomon Moriba, a spokesman for the court in The Hague.

Moriba said any relationship Taylor had with American intelligence was not related to his case before the court, but those who investigated the atrocities said it might explain why some US officials seemed reluctant to use their influence to bring Taylor to justice sooner.

After Taylor stepped down as Liberian president in 2003 following his indictment, he lived virtually in the open for three years in exile in Nigeria, a US ally. The Bush administration came under intense criticism from members of Congress for not intervening with the Nigerian government until Taylor was finally handed over to the court in 2006.

Allan White, a former Defense Department investigator who helped build the case against Taylor on behalf of the United Nations, said the news reinforced suspicions he had for years.

“I think the intelligence community’s past relationship with Taylor made some in the US government squeamish about a trial, despite knowing what a bad actor he was,’’ White said in an interview.

Taylor’s lawyer in the war crimes trial, Courtenay Griffiths, did not respond to several calls or e-mails seeking comment.

The Pentagon’s response to the Globe states that the details of Taylor’s role on behalf of the spy agencies are contained in dozens of secret reports – at least 48 separate documents – covering several decades. However, the exact duration and scope of the relationship remains hidden. The Defense Intelligence Agency said the details are exempt from public disclosure because of the need to protect “sources and methods,’’ safeguard the inner workings of American spycraft, and shield the identities of government personnel.

Former intelligence officials, who agreed to discuss the covert ties only on the condition of anonymity, and specialists including Farah believe Taylor probably was considered useful for gathering intelligence about the activities of Moammar Khadafy. During the 1980s, the ruler of Libya was blamed for sponsoring such terrorist acts as the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing over Lockerbie, Scotland and for fomenting guerrilla wars across Africa.

Taylor testified that after fleeing Boston he recruited 168 men and women for the National Patriotic Front for Liberia and trained them in Libya.

Over time, the former officials said, Taylor may have also been seen as a source for information on broader issues in Africa, from the illegal arms trade to the activities of the Soviet Union, which, like the United States, was seeking allies on the continent as part of the broader struggle of the Cold War.

Liberia, too, was of special interest to Washington. The country was founded in 1847 by freed American slaves who named its capital, Monrovia, after President James Monroe. The American embassy was among the largest in the world, covering two full city blocks, and US companies had significant investments in the country, including a Firestone tire factory and a Coca-Cola bottling plant.

A former ally of Taylor’s, Prince Johnson, told a government commission in Liberia in 2008 that he believed US intelligence had encouraged Taylor to overthrow the government in Liberia, which had fallen out of favor with Washington for banning all political opposition.

Taylor’s ties to Boston reach back four decades.

He arrived in 1972 and attended Chamberlayne Junior College in Newton and studied economics at Bentley College in Waltham. While in Boston, he emerged as a political force as national chairman of the Union of Liberian Associations. In 1977 he returned to Liberia and joined Samuel Doe’s government after a coup in 1980.

Taylor served as chief of government procurement in the Doe regime but fled Liberia for Boston in 1983 after being accused of embezzling $1 million from the government. He was arrested in Somerville in 1984 and jailed in Plymouth pending extradition.

The acknowledgment now that Taylor worked with US intelligence agencies at the time raises new questions about whether elements within the government orchestrated the Plymouth prison break in 1985 – as Taylor claimed during his trial – or at least helped him flee the United States.

Four other inmates who also escaped that night were soon recaptured.

“Why would someone walk out of a prison that’s never been breached in a 100 years?’’ said David M. Crane, who was the chief prosecutor for the Sierra Leone war crimes court from 2002 to 2005 and now teaches at Syracuse University College of Law. “It begs the question: How do you walk out of a prison? It seems someone looked the other way.’’

Taylor recounted the episode during his trial testimony, insisting that a guard opened his cell for him.

“I am calling it my release because I didn’t break out,’’ Taylor testified. “I did not pay any money. I did not know the guys who picked me up. I was not hiding [afterwards].’’

He said two men – he assumed they were American agents – were waiting for him outside the prison and drove him to New York to meet his wife. Using his own passport, he said, he traveled to Mexico before returning to Africa.

Brian Gillen, the superintendent of the maximum security jail in Plymouth who was director of security at the time of Taylor’s escape, declined to comment when reached last week by the Globe.

Taylor reemerged in Liberia in 1989 as head of a rebel army.

“I assigned an officer to maintain a watch on the Taylor people,’’ recalled James Keough Bishop, US ambassador in Liberia from 1981 to 1989.

Bishop said he was not aware of ties between American intelligence and Taylor.

After a series of bloody civil wars that lasted much of the 1990s, Taylor eventually assumed power. He was elected president in 1997.

Several former officials and specialists believe US intelligence had probably cut ties with Taylor by the time he became president, but Farah said he believes that even in the early years of their associations with Taylor, US intelligence agencies knew what kind of character he was.

“Even at the time, there were atrocities going on,’’ he said. “He wasn’t clean when they hooked up with him. We had a high tolerance for people who were willing to inform on Khadafy. The question is whether he actually provided anything useful.’’

CULLED FROM

Leave a Reply