ALBRIGHT MEETS SIERRA LEONE REBELS

|

By Karl Vick

Washington Post Foreign Service

Tuesday, October 19, 1999; Page A12

FREETOWN, Sierra Leone, Oct. 18—Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright, meeting face-to-face with people who lost limbs to rebel machetes during Sierra Leone’s shockingly brutal civil war, extended her hand to adults who offered only a stub in return. She picked up a smiling 2-year-old girl who clutched a toy car in the one hand she has left.

“Coming to Sierra Leone is a humbling experience,” said Albright, who made her first visit here today–and to Guinea and Mali as well–at the start of a six-country African tour.

It was that, and more. At her next stop in Freetown, the capital, Albright met with leaders of the rebel forces who committed the atrocities during eight years of chaos and killing that have left this West African country in shambles. They are reviled figures who nevertheless have received amnesty and are headed for senior government positions by dint of a peace deal that U.S. officials helped broker.

The secretary, who would not be photographed with the rebels, defended giving them immunity, calling it the price of a peace so desperately needed after a struggle for power in which severing limbs was a common rebel tactic. “It was very important to seize the moment,” she said. But even as she took pains to bolster the fragile accord–the rebels have not begun disarming as promised–Albright also acknowledged that it fails to satisfy a fundamental yearning for justice.

“Ultimately, the only way reconciliation really can come is if people have a sense that justice has been done and those who have perpetrated the terrible crimes are punished individually,” Albright said at a news conference.

The peace accord signed July 7, she noted, grants immunity only in Sierra Leone. And a footnote added by the United Nations points out that war crimes prosecution remains a possibility under international law. Albright voiced support for an international tribunal only in principle, however, saying she prefers to “keep that as something that we might come to.”

The U.S. priority, Albright made clear, is to hold together a country riven by war since 1991. To that end, she announced plans for $55 million in aid. Most would go to food and disaster relief. But $4 million would help educate child soldiers after they lay down their arms, and $1 million would go toward establishing a certification process intended to undermine illegal trade in Sierra Leone diamonds, the sale of which fueled the rebel insurgency.

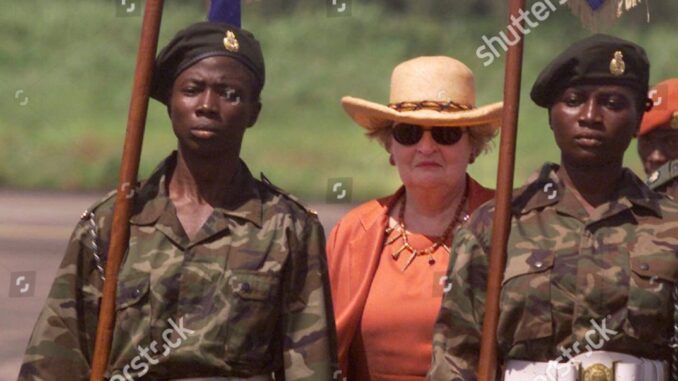

ALBRIGHT United States Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, flanked by soldiers from the Sierra Leonean Army, is led through a quick inspection of troops from the Nigerian led peacekeeping force, ECOMOG, shortly before departing the Sierra Leonean capital Freetown, . Albright visited the war-ravaged country on her first day of a six-nation African tour

SIERRA LEONE ALBRIGHT AFRICA, FREETOWN

A State Department official said the legitimate diamond industry, wary of a consumer backlash over illicit diamond sales financing African wars, is eager to establish a way of “marking” diamonds to indicate they are legal. The issue is especially pressing in Sierra Leone: As part of the peace deal, Foday Sankoh, leader of the rebel Revolutionary United Front, was named head of a commission that will determine the fate of the country’s diamond mines.

Albright met briefly with Sankoh and the other major rebel leader, Johnny Paul Koroma, at the residence of the U.S. ambassador. A person present said the secretary told both men the world was repulsed by their forces’ atrocities–20,000 people have been killed and an unknown number mutilated–then urged them to abide by the peace accord, which calls for disarmament, demobilization and reintegration of rebel troops.

Albright reviewed the Nigerian forces who have served as Sierra Leone’s army for most of the decade, as the mainstay of the regional multinational force known as ECOMOG. The Nigerians are expected to be replaced by a 6,000-strong U.N. peacekeeping force under terms still being decided by the Security Council.

Meanwhile, U.N. military monitors have been arriving by the dozen to supervise a rebel disarmament that was to begin more than a month ago. The process was delayed in large part because Sankoh and Koroma, who directed the rebellion from afar, only recently returned to Sierra Leone to urge their forces to abide by the accord.

“They say they’re talking to their guys, which is more than they were doing last week,” said one senior U.N. officer, who asked not to be named.

Many here warn, however, that whatever the fate of the peace accord in the short term, Sierra Leone will not find lasting peace until justice is done. The July accord includes a provision for a “truth and reconciliation commission,” but critics call it window dressing in a conflict where it is only too obvious what has been done.

Corinne Dufka, a researcher for the New York-based Human Rights Watch and a Freetown resident, said she has documented atrocities, including “attempted mutilations” and a gang rape, that took place as recently as two weeks ago.

“It’s clear if there’s a general amnesty that the cycle of impunity is not broken,” she said.

Francis Josiah had the same thought. Seated among the amputees after shaking Albright’s hand, he warned of the consequences if the men who also set him on fire are never held to account.

“Oh, yes, the peace is better,” said Josiah, 42. “But justice should not be left behind. Because we do not want people to practice such activity next time in this country.”