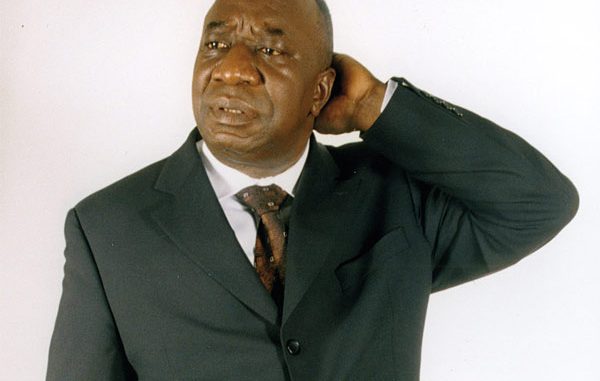

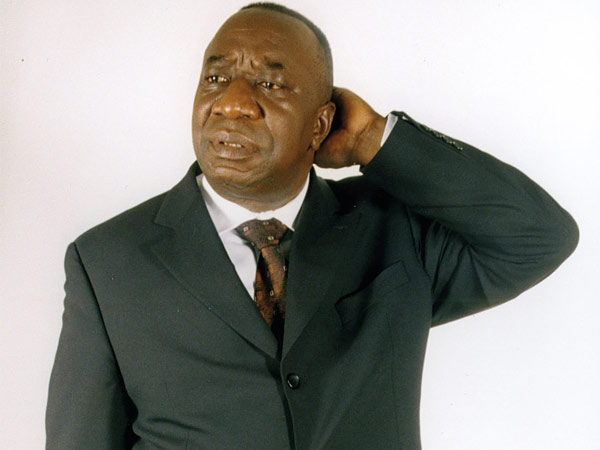

Tabu Ley Rochereau, a Congolese singer, songwriter and bandleader whose music spread across Africa and the world, died on Nov. 30 in Brussels.

Mr. Tabu’s voice, a high tenor, was always sweetly urbane, whether he was singing of love, his Christian beliefs or social issues. From the 1960s into the ’90s, he led one of the two top bands playing soukous, the Congolese rumba that became popular across Africa. He wrote and recorded thousands of songs, and as a bandleader and arranger he widely expanded the sound of soukous, infusing it with both local African rhythms and elements of international pop.

Soukous is an African reclamation and reinvention of Afro-Cuban music, particularly the son and the rumba, with gentler, smoother harmony singing and endlessly entwining guitar lines. Mr. Tabu’s band, Orchestre Afrisa International, was rivaled only by Le Tout Puissant OK Jazz, led by the guitarist Franco. (Franco, whose last name was Luambo, died in 1989.)

The contrast between their approaches has been compared to that of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, with Mr. Tabu more suave, Franco more aggressive. But the two rivals also collaborated at times on albums like “Omona Wapi.” The best introduction to Tabu Ley Rochereau’s career is found on two two-CD anthologies: “The Voice of Lightness, 1961-1977” and “The Voice of Lightness, Vol. 2,” both on the Sterns label.

Tabu Ley Rochereau was born Pascal Emmanuel Sinamoyi Tabou in what was then the Belgian Congo. He went by simply Rochereau, a school nickname, when he sent his first songs to Joseph Kabasele, the leader of the pioneering Congolese rumba band Orchestre African Jazz. He made his first recordings with another band, Rock-a-Mambo, in 1958, but had his first hit, “Kelya,” after he joined African Jazz in 1959, singing harmony with Mr. Kabasele’s lead. (Mr. Kabasele died in 1983.)

As the 1960s began, Rochereau wrote many hits for African Jazz when it was Congo’s top band. But in 1963, he took five members of African Jazz with him to start his own band, African Fiesta.

Congo, which had become an independent state in 1960, sent African Fiesta to Expo 67, the world’s fair in Montreal, where Rochereau soaked up North American rock and soul; he added a trap drum kit to his band. Three years later he took African Fiesta to Paris to perform, and in 1972 he made an album in London; the band soon became Afrisa International. After the regime of Mobutu Sese Seko changed Congo’s name to Zaire in 1971 and called for the nation to reclaim African “authenticité” from colonial influences, Rochereau renamed himself Tabu Ley Rochereau.

Afrisa International was a sensation across Africa in the 1970s. Mr. Tabu had his own label, Isa, and his own club, Type K, in Kinshasa, Zaire’s capital. In 1981, he discovered a 22-year-old singer, Mbilia Bel, who joined his band and turned his songs into Zaire’s top hits. They also had a child together, Melody.

As Zaire’s government grew more dictatorial and the country’s economy foundered, Mr. Tabu took the band abroad for long stretches. By the end of the 1980s Afrisa International was touring Europe, Africa and North and South America.

The band was based in Paris when riots shook Kinshasa in 1991, and Mr. Tabu told a journalist he would not return to Zaire until conditions improved. A government spokesman responded that he would be unwelcome.

While in Paris, Mr. Tabu recorded the album “Exil-Ley,” which contained his most directly political song, “Le Glas a Sonné” (“The Bell Has Tolled”). “We won independence to lift up our people/But our own leaders fought among themselves,” he sang. “Grabbing what they could, ignoring the people./Now the country is ruined.”

In 1994, Afrisa International moved to the United States, where it toured clubs and festivals and added English lyrics to its songs. But after Mr. Mobutu was ousted in 1997, Mr. Tabu returned to his native country, which had been renamed the Democratic Republic of Congo, and plunged into politics.

He was a founder of the Congolese Rally for Democracy party, and he became a cabinet minister, a member of parliament and vice governor of the city of Kinshasa while continuing a reduced recording career. He was in Kinshasa when his stroke debilitated him in 2008, and he was moved to Brussels for medical care.

Among his many surviving children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren are, besides his son Marc, four sons who became musicians: Pegguy Tabu, Abel Tabu, Philemon and the French rapper Youssoupha Mabiki, who sampled his father’s music on a 2012 single,“Les Disques de Mon Père.”

NEW YORK TIMES

Leave a Reply