Titus Boye-Thompson

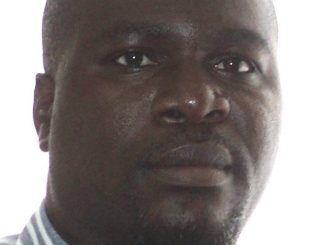

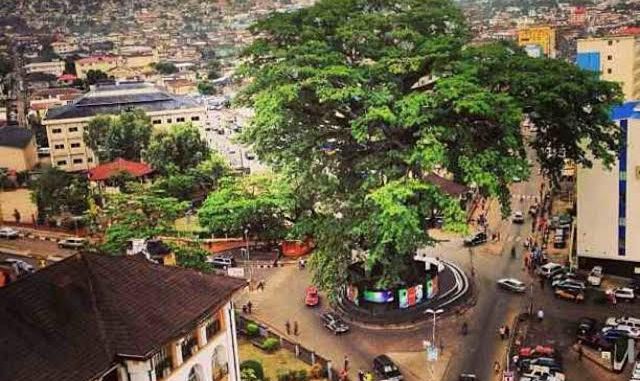

It was Grahame Green who wrote the epic tome, “the heart of the matter,” a book that became an all-time bestseller. Significantly, Grahame Green became more popular for his travelogues which provided graphic pictures of empire and British garn living in the colonies. He mentioned Freetown in one of his travel stories and made such references to City Hotel and the new Lebanese community that was growing within the colony as a separate class between the White men and Colonial Administrators and the indigenous people of this city. He painted a picture of serene town, a city full of life and leisure but nonetheless a momentous colonial outpost where white men and the Lebanese lived a joyous life at the expense of the very pliant local indigenous peoples. He made some scant references to the upcoming Creole class but never went beyond the cover of their astute Englishness as civil servants underpinning the British colonial administration.

Grahame Green’s depiction of Freetown in those days came at a time when the World was less close, when travelling from Freetown to Kenema took all of three days and when there were no mobile phones to announce your coming at any time before your arrival. Those times evoke a sentiment of goodwill and opportunity. The economic dispensation was admittedly neo-colonialist which mandated a one sided relationship between colony and the governed. The expansion of colonial administration to the rest of the country created a dichotomised environment that separated the colony from the “Protectorate” and with that differentiation came a whole raft of laws, customs and traditions that have impeded the growth of this country as one nation. The existence of two distinct and separate land management systems for example remains the greatest damage that was done to the spatial development of this country. The fractious nature of this situation has been the greatest disappointment from this country’s history and will continue to be the most difficult issue to manage. This situation is now outside of politics unless there is an agreement to undertake massive reengineering of our social structures.

Sierra Leone is easily becoming irrevocably broken on account of the strained relations that our historical decisions now weigh down on present generations. The fight for political power and authority continues to rage even in the face of calamity and natural disaster. There is a seeming acceptance that politics must be aggressive and antagonistic. That people should be aligned as to tribes and regions as if they are going to war. The context of them and us remain to be the widest wedge that strangles this country but no one seem to have an idea of how to deal with the chasm that this divisive politics has created. In the event, the country is left to wallow in destruction and degeneration because our people see themselves as belonging to camps and corners of tribal and regional colours instead of being separated by ideologies of intellectual import.

Many observers relate the dysfunctional political system that is mow emerging to this same historical infighting depicting itself in another more divisive flavour with the array of alternative political parties clamouring for the demise of what is already accepted as one of the most successful governments for a very long time. Were Grahame Greene to have been here, it is clear that even if he would not have depicted Sierra Leone in the same terms but at the same time, he would have mentioned the conduct of good governance, the peace and tranquillity enjoyed by the citizenry and the network of good roads that connect any seasoned traveller to the outer reaches of Kono and Kabala, two of the places he would have wanted so much to see. One for its natural mineral resources and precious stones of Diamond and the other for its picturesque hills and mountains of the Wara Wara.

In these times of indeterminate social and political predictions, one is tempted to infer that the end of history as Fukuyama stated, would be even more of a reality than a prospect. Having said this, it is more a matter of a country seized of the propensity for violence and calamity on the basis of a more amenable interpretation of peace and security hovering the climate that is really the cause of its own resignation to serenity. The people of Sierra Leone are not as easily led to violence and unrest that some do imagine it to be.

Sierra Leone made a swift move from its neo-classical, post colonialist economic era to engage fully within the global challenges of modernism and neo-liberalist doctrine. The economy suffers equally in times of global slump in the prices of precious metals and mineral ores and as well enjoys the benefits of a strong world economy for industrialisation and metal products used mainly in shipping and construction or heavy industries, The luxury markets of Gold and Diamonds remain a steady source of income to a country where a Pastor in a small town could still reach the headline and capture the national interest with a find of a single diamond.

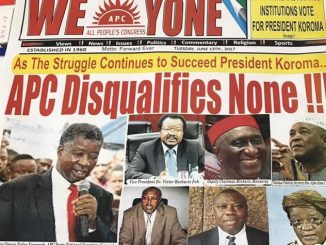

Notwithstanding the ruptures of a fragile state and a fledgling democracy, this country holds its head up high amongst the World community of nations and this has been in part, due to the deliberate strategy of the Ernest Bai Koroma’s government to take the diplomatic high ground and engage in some of the most strategic diplomatic alliances of this time. President Koroma’s Chairmanship of the African Union’s Committee of 10 assured him global recognition and an easy ally to his African friends and neighbours. His steady improvements in African peace making has also been a significant plus to his appeal for a more proactive stance that this country can take within the realms of regional and sub-regional integration and expansionist policies of the neo-liberal order.

While it is clear that Sierra Leone may have had to move on from those halcyon days that Grahame Green describes, the rationale for closer reflections on the situation that the country finds itself is still a valid starting point in any analysis of its future potential and promise. Going back to the heart of the matter, as Greene puts it, relies on a rational assessment of the strides that has been made, given the challenges that the leadership has had to tangle with. The challenges of engaging in free market dynamism of the neo-liberal World economic order mean that Sierra Leone yields its economic destiny to the forces of market demand. Having no control whatsoever on the prices that the World market demands for its mineral ores and precious metals is in itself difficult to contend with but the investments necessary to create the added values of economic multiplier in the local economy is too high to be borne by the public purse, to the extent that the exploitation of its mineral ores have to be left to the market leaders in such high end industrial mining concessions that the net value to the economy being at some times at variance with local expectations is itself a bitter pill to swallow.

From these discussions, two things are beginning to become clear. Firstly, we must strive to engage on a discussion about what makes us a nation together. The prospect of a one nation politics is not too farfetched because such a concept begins to address the borders set up against the deliberations of political questions on the basis of ideology rather than on a myopic and single minded view of tribe or region. Such a reflection would include considerations of how we could bring this country under a single platform that is focussed on development, the creation of a vibrant and fully functional socio-economic geo-dynamic that provides benefit to all.

Secondly, we should strive to rebuild the political and social demarcations that such strained frameworks of regions and tribes have inflicted on this place, this land that we love. In contemplating that rebuild, we should be willing to relieve ourselves of the notions of separateness and subjectivity. The traditional; attachment to land could for example be yielded to a more functional management dynamic that allows land to be transferred for long and economic leases with the eventual title being reversionary but not necessarily actionable without recourse to a fair legal jurisdiction of competent luminaries and justices. This would mean that all determinations of land must be actionable in as singular system of arbitration and jurisprudence with varying degrees of influence. The traditional Chiefs would still settle minor land disputes or traditional issues relating to land and the disposal thereof, but when it comes to economic land or land that has been put into economic use, the determination of its title must be actionable in the higher courts of adjudicature.

The heart of the matter is therefore directed to these two considerations of a fairer method of political discourse and an equally fair administration of land use and management for the benefit of all Sierra Leoneans, their heirs and assigns. To start on this road would need sheer drive and a whole new vision. The concept of one nation politics is already out there. What we need now is to integrate that concept into the Agenda for Prosperity so that they can together provide the framework for development and a sense of achievement that President Ernest Bai Koroma has been preaching for throughout this time of his tenure.