By Esteban L. Hernandez, New Haven Register

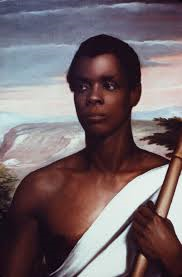

Nathaniel Jocelyn’s 1839 portrait, “Cinque,” depicting the leader of the Amistad mutiny. Amistad Committee members prefer using the name Sengbe Pieh. New Haven Museum Collection

NEW HAVEN : A few weeks ago, the New Haven Museum received a curious letter from a man in Scotland, according to Amy N. Durbin, a museum educational director.

The man claimed to be a distant relative of Robert Purvis, who is famous for commissioning New Haven’s Nathaniel Jocelyn to paint a portrait of Sengbe Pieh, or Cinque, the African captive who served as leader of the Amistad Rebellion in 1839.

Durbin said Purvis was the son of a white plantation owner and a mixed race woman. He spent his life working as an abolitionist based in Philadelphia. Sengbe Pieh, a farmer in his native Sierra Leone, was 25 when the image was painted, and it depicts the revered leader in a stoic, heroic repose. The work is famous for being perhaps the first illustration by an American artist of an African man as a luminary figure rather than a slave.

The Scottish man wanted to know where this illustrious painting was, to see what had become of the painting crafted by his ancestor, according to Durbin.

“(He) asked if we knew anything,” Durbin said.

So what was the museum’s response?

“Well, we have it,” Durbin said, while standing in front of the painting, which has been in the museum’s possession since Purvis gave it to them in 1898.

“We sent him a postcard image of it. We sent him like a journal about the Amistad and said, ‘if you needed any more information, to let us know, because he didn’t know we had it,” Durbin said.

The portrait is encased in a thick, plastic barrier that helps with its preservation. It’s the focal point of the museum’s Amistad exhibit. And in a building showcasing countless invaluable artifacts, the 135-year-old piece remains one of the museum’s most prized possessions.

“This is the iconic image. When you type in ‘Amistad’ in Google search, you’re going to show up with this portrait,” Durbin said. “It’s like the gem of our collection.”

The legacy of the Amistad continues to enchant the Elm City more than 170 years after the Supreme Court ruled that the African captives taken from Sierra Leone were legally free. It’s often cited as one of the first major civil rights victories in American history. Its significance to American and local history are why the city is hosting a 175th anniversary commemorative banquet on Wednesday, to celebrate the decision and acknowledge its value in history. It’s being organized by the local Amistad Committee.

“I am really proud of that history,” Mayor Toni Harp said. “I think everyone in New Haven as well as Connecticut should be proud of this history and what it’s meant for the fight for freedom. Some of what happened here impacted across the world.”

Memorializing a legacy

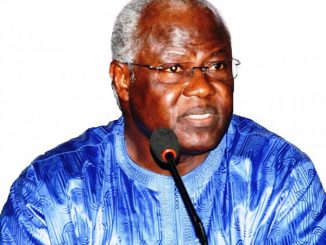

It’s hard to say whether Al Marder’s basement is a celebration of him or of all the folks he’s helped. A closer look at the many accolades offers some direction.

Hanging from several walls are various state and local citations and proclamations from governors and mayors. There’s also a few that hint at his international recognition; there’s at least three from federal offices in Latin American countries, one from Europe and another from Africa — from Sierra Leone, in fact. They recognize his decades-long humanitarian work as a civil rights advocate.

“Al Marder has made so many contributions to this community,” Harp said. “From the work he has done for labor rights, to the work early in his life to the work he’s done for peace, and trying to really focus on brotherhood.”

On his desk, among the scattered documents, photos and office supplies, Marder, 94, pulled out a little replica statue of the Cinque sculpture erected outside City Hall in 1992. The statue was built thanks to his guidance and supervision. A similar replica sits at the New Haven Museum’s Amistad exhibit. He fished it out two weeks before the ceremony, which he’s planning to attend. Marder is chairman of the Amistad Committee, which is helping organize the ceremony.

“I think it’s an opportunity for people to realize that in this period, where black lives matter,” Marder said, referring to the national movement sparked after the deadly shooting of unarmed black men, “that black lives mattered to a group of New Haveners 175 years ago.

“The struggle against slavery and the struggle against racism has been a long struggle and it continues today, in a different form, but it’s in the headlines of our newspapers,” Marder said.

Marder believes the ruling helped spark the abolitionist movement in the United States, a movement that would reach a crescendo with the Civil War 20 years later. Slavery was still legal in Connecticut when the Amistad ruling took place; the Nutmeg State wouldn’t abolish slavery until 1848.

“You have to move yourself back into the period to see how courageous the abolitions were. And that’s hard for people to do,” Marder said.

During the 150th anniversary celebration in 1991, Marder was approached by local ministers to organize celebratory events. He was chosen partially because of his strong ties to the local community, but because since he started a peace council while a student at Hillhouse High School, he’s always been something of a peacekeeper.

“I had known the story because I read it myself, not in the schools; it was not discussed,” Marder said. “We decided that we had the responsibility of telling people how important (the decision was).”

While plans were made for the 150th anniversary, organizers concluded the city needed a permanent memorial. So money was raised, with jars placed in banks and stores and children urged to collect funds through penny drives. Even then, Marder remembers having to retell the story of the Amistad captives, since most people weren’t familiar with their legacy. It only motivated him to continue raising money for a permanent statue.

“Today, young people in particular, must know the story to inspire them for today,” Marder said. “That’s extremely important. It’s the same history, the same struggle in a different form.”

A nationwide search to find a sculptor was launched after the money was raised. Marder knew it was important to ensure an African-American artist was chosen to create the memorial. So the applications calling for sculptors were sent to historically black colleges.

Five submissions were accepted, with artists submitting portfolios. A jury was compiled, but none of the five made the cut. So Marder said they asked the five sculptors to resubmit. Three were invited to come to the city. But only one sculptor obliged: Southerner Ed Hamilton, a Spalding College graduate who was in midst of becoming an accomplished sculptor.

“My reply was, well, since they’re not here, I get the job, right?” Hamilton said over phone from Kentucky. But it wasn’t that easy; he still had to come up with a design. “I came back to Louisville, I thought, ‘Oh Lord, what do I do? What do I do?”

Hamilton has not been back to New Haven in more than 10 years. He’s scheduled to attend the ceremony this week and then speak to local students about his work. He remembers submitting his work for the competition, unsure of what the committee sought.

“I didn’t know the history of it myself at that point,” Hamilton said. “It wasn’t anything that was taught to me when I was going to school.”

The dedication was held in September 1992. The 10-foot sculpture depicts Sengbe Pieh as he would have dressed in his native Sierra Leone and during the trial.

The statue sits in the area where the captives were held after being apprehended off the coast of the United States. Marder asked Harp, then a city alder, to accept the statue in that space when the idea was first introduced.

The New Haven Museum has some of the keys from the jail were the Africans were kept. Durbin said jailers sold tickets to see the captives for 12 cents. Marden said the sheriff supervising the imprisoned Africans would take them to the city Green to allow them exercise, charging a fee for people to watch.

“He claimed he was using the money to feed them. They claim he was using the money for themselves,” Marder said.

Marder sees the present in the past. And he wants to ensure that present-day folks continue to recognize the contributions that led to one of the most significant human rights decisions in American history.

“We’re not living just in the past,” Marder said. “But you can’t move forward until you know your past.”

Struggle and perseverance

Hamilton knew his task wasn’t simply about creating a memorial. It became immediately clear that his work was meant to tell a story, one that simultaneously embodied struggle and perseverance. After Sengbe Pieh led a revolt on board the Amistad (which, ironically, means “friendship” in Spanish) in 1839, that’s what the African captives encountered.

After the United States seized the ship near Long Island and brought it to New London, they sent the captives to jail in New Haven. It would be two years before the Supreme Court would rule that the capture and transport of the Africans was illegal, since the international slave trade had been abolished by that time.

“They were looking for a narrative to tell more of a story than just having him stand up there,” Hamilton said. “What I tried to portray is putting Sengbe Pieh in context of this incident. If it had just been a free-standing sculpture, I just didn’t think that would be enough for people to comprehend what this Amistad incident was all about.”

The statue needed to tell a story. Hamilton decided to focus on three acts: Sengbe Pieh in his homeland, the man during the trial phase and finally, during his farewell, as he embarked on his return to his native continent.

At the top of the sculpture, Hamilton included a special commemoration. Marder said there’s a leg and a hand appearing amid waves, which he said is Hamilton’s tribute to slaves who drowned after being captured. Marder said this is visible from the mayor’s office.

Hamilton believes the hands and feet may be visible from the ground at a certain angle.

“You will actually see a symbolistic image of a dying soul in a murky, watery grave. It represents the souls that did not make it,” Hamilton said.

In an odd way, Hamilton feels thankful the Amistad Africans were kidnapped. After all, their capture led not only to their freedom, but it allowed their story to be told and retold.

“They were not born in America, if they had been slaves, they would (not have) been set free,” Hamilton said. “(They) were kidnapped out of their country; that was a blessing.”

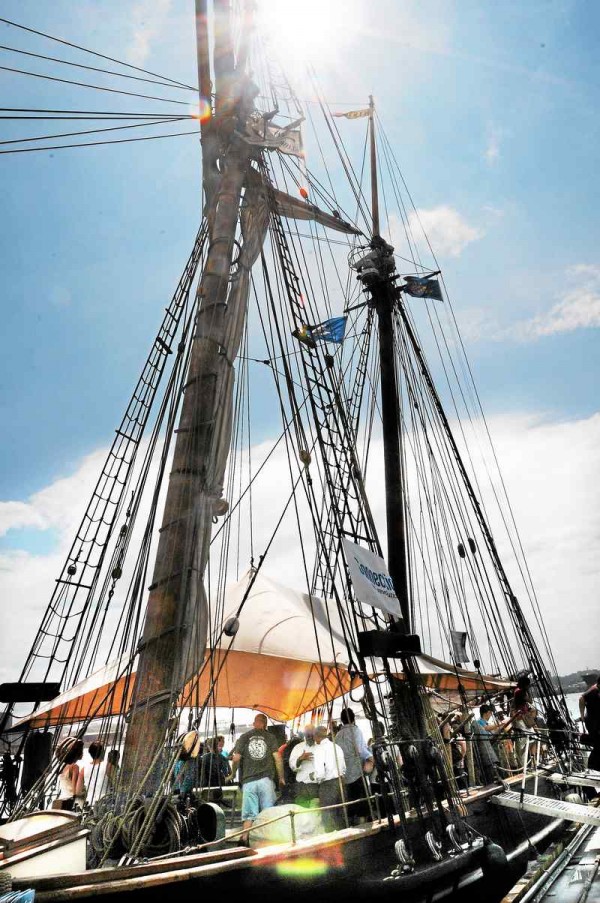

The commemorative banquet takes place at Amarante’s Sea Cliff at 62 Cove St. from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. Wednesday. More information on tickets, which must be purchased in advance, can be found online at amistadcommitteeinc.org .