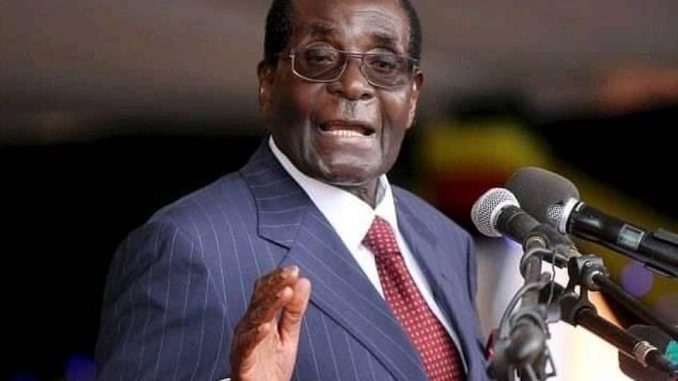

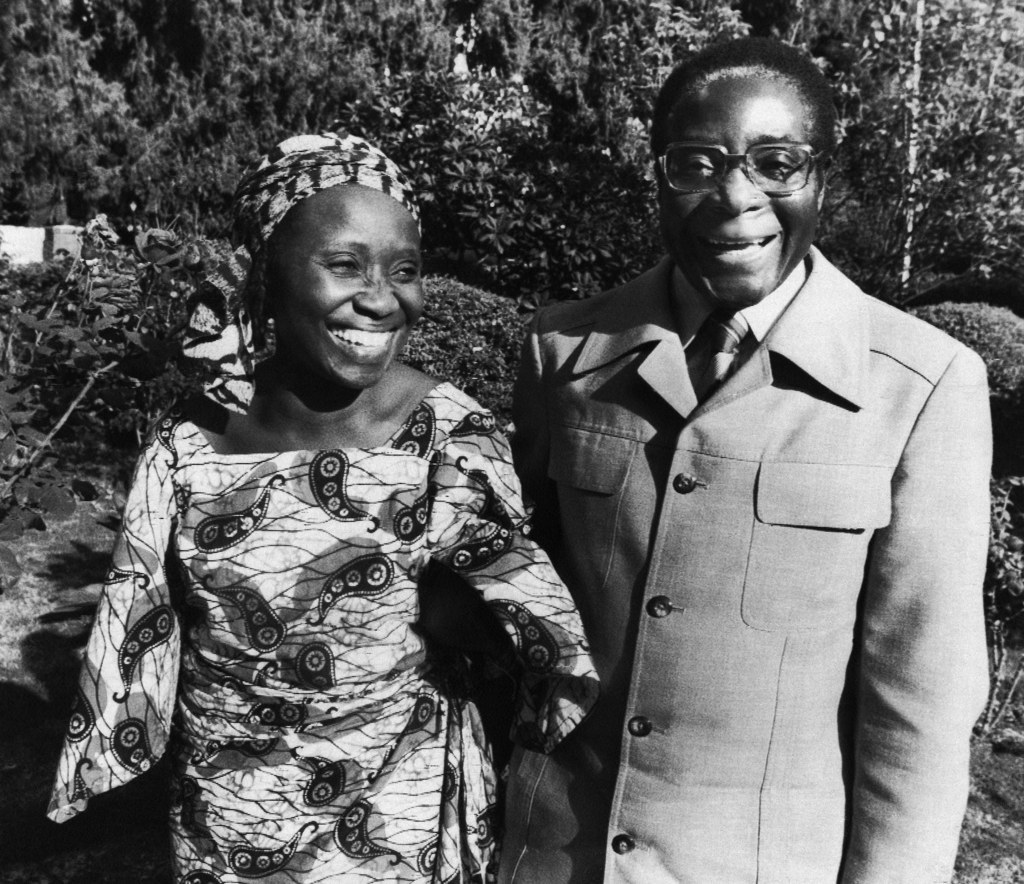

From jailed militant, to first leader of an independent Zimbabwe, to long-reigning dictator, Robert Mugabe left a lasting mark on the region.

Philimon Bulawayo / Reuters

Robert Mugabe, the former political prisoner, first black leader of an independent Zimbabwe, and unrepentant strongman, has died, the nation’s current president announced Friday. He was 95.

“Mugabe was an icon of liberation, a pan-Africanist who dedicated his life to the emancipation and empowerment of his people. His contribution to the history of our nation and continent will never be forgotten. May his soul rest in eternal peace,” said Zimbabwe President Emmerson Mnangagwa in a tweet announcing the former leader’s death. The government of neighboring South Africa also paid tribute to Mugabe in a tweet.

Mugabe had been receiving treatment in a hospital in Singapore for several months.

It is with the utmost sadness that I announce the passing on of Zimbabwe’s founding father and former President, Cde Robert Mugabe (1/2)

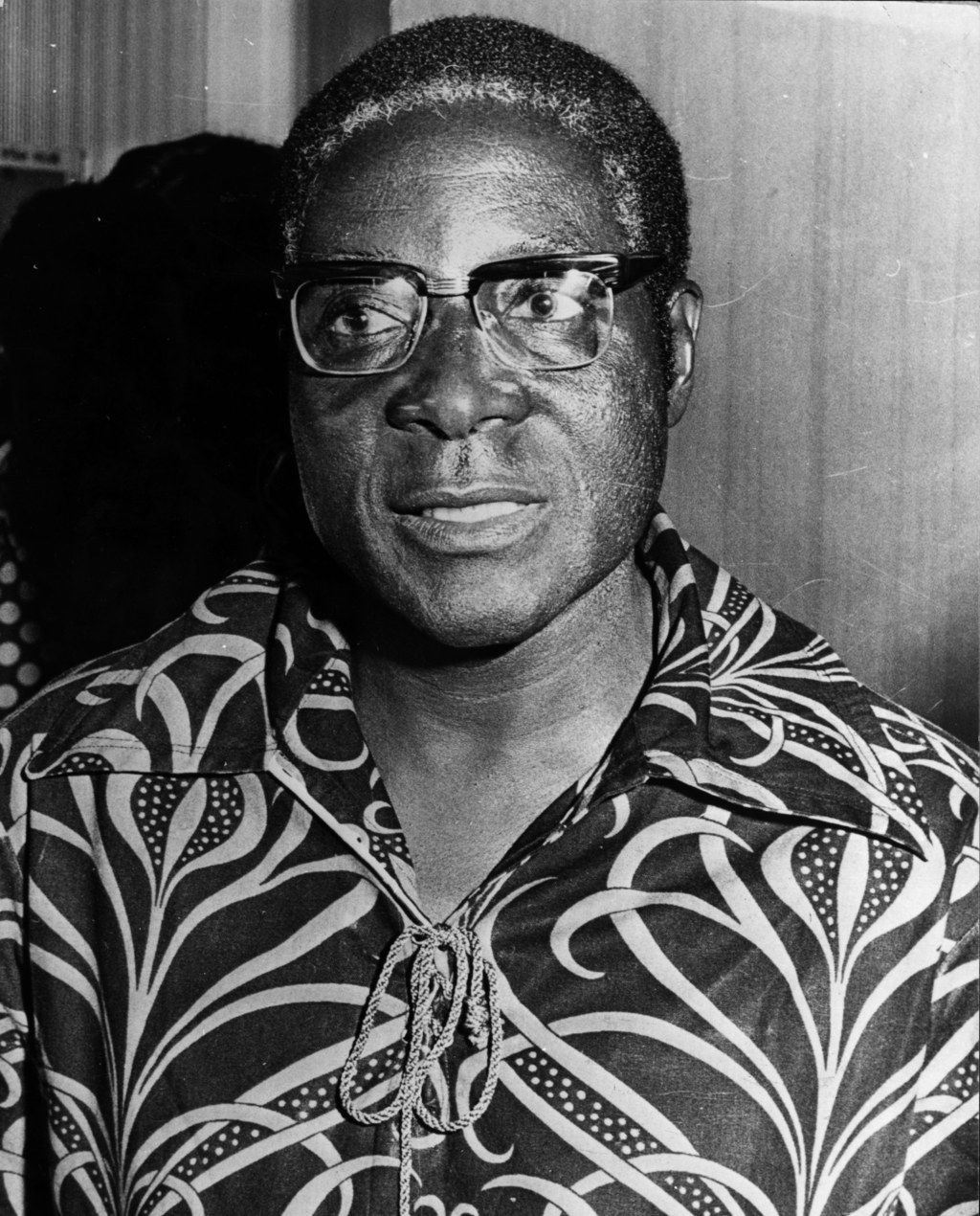

Long before he became one of Africa’s longest serving dictators, Robert Gabriel Mugabe was born on February 21, 1924 to a family in what was then known as Southern Rhodesia, a British colony ruled by a white-minority government.

A scholarly child, Mugabe was raised as a Roman Catholic, and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Fort Hare in 1951. Following graduation, he spent time as a teacher in Rhodesia and traveled to Ghana — where he was inspired by then-Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah’s success after the country’s independence movement.

After returning to Rhodesia, Mugabe immediately joined a political party that the white minority-led government soon thereafter banned. It swiftly reformed as the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (ZAPU), which followed the Soviet Union’s notion of supporting marginalized urban workers, in 1961

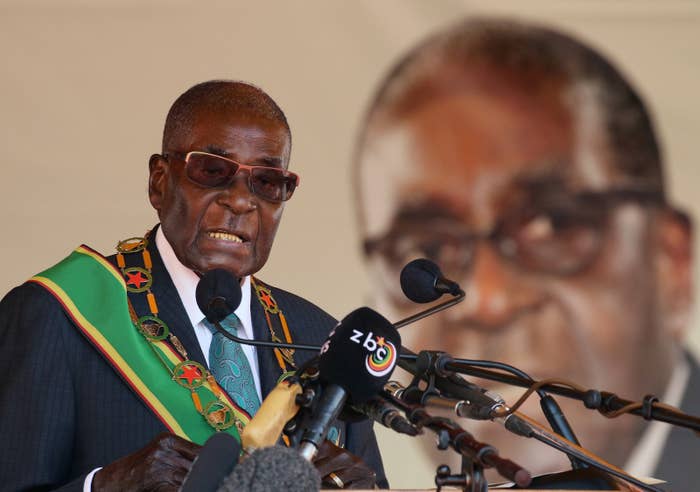

Keystone / Getty Images

Members of ZAPU including Mugabe split off to form the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), more influenced by Maoism’s focus on rural farmers. Tensions between the two groups spilled into violent conflict, leading to both being banned.

Mugabe was, along with other ZANU and ZAPU leaders, arrested in 1965. After years in prison, Mugabe was elected the head of ZANU in 1974, before being released in December of that year.

AFP / Getty Images

The so-called “Rhodesian Bush War” pit ZANU, ZAPU, and the Rhodesian government against each other during Mugabe’s time in prison and after.

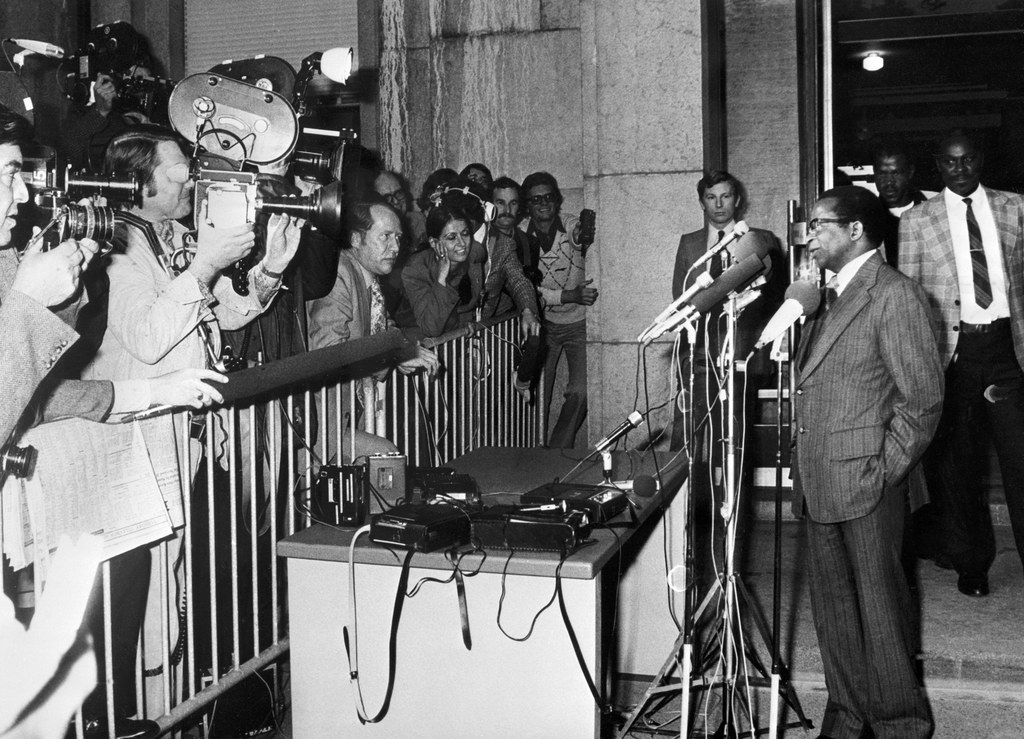

By 1980, a combination of international sanctions and fighting a war had left Rhodesia unable to continue resistance against its black majority. In the country’s first open elections, Robert Mugabe won his campaign for president. In 1987, ZANU and ZAPU formalized their alliance and became ZANU-PF: Zimbabwe African National Union — Patriotic Front.

Louise Gubb / AP

The fear at the time was that whites would flee the country in a mass exodus. Mugabe sought to reassure them of their ongoing place within the renamed Zimbabwe.

“The whites are here. They are still in control of the economy, the majority being commercial farmers,” Mugabe told CBS in a 1994 interview, 14 years after taking office, when South Africa’s Nelson Mandela was preparing to be sworn in.

Alexander Joe / Getty Images

But six years later Mugabe reversed course, demanding that the United Kingdom — which backed Rhodesia’s government — pay for the economic cost white leadership levied on his country. When the UK refused, Mugabe began seizing farms for redistribution.

The first round of seizures in 2000 drew international condemnation and recast Mugabe from a freedom fighter to a pariah. By 2004, Zimbabwe — which had once been considered Africa’s breadbasket — had 5.5 million citizens in need of food aid.

Throughout his term in office, as well, Mugabe had been accused of rigging the elections that kept him president. In the 1996 election, for example, Mugabe announced that he had won with over 92% of the vote — despite only 30% turnout at the polls.

Sarah-jane Poole / ASSOCIATED PRESS

In the 2008 elections, amid the country’s faltering economic situation, Mugabe found himself in a run-off with opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai. The resulting violence the government unleashed against his supporters convinced Tsvangirai to withdraw.

The situation within the country failed to improve afterwards, despite a power-sharing agreement that nominally had Tsvangirai become Prime Minister.

“The power-sharing government’s pledge after the 2008 elections for human rights reforms has been all talk and no action,” said Daniel Bekele, Africa director at Human Rights Watch, in 2011. “The government’s failure to punish the attackers only emboldens those intent on committing political violence and torture.”

A rematch between the two in 2013 saw Mugabe victorious yet again. Zimbabwe’s Electoral Commission at the time said that some 305,000 voters were turned away during the elections, while another 207,000 voters were “assisted” with their ballot. Mugabe won by some 900,000 votes. (Tsvangirai died at the age of 65 in February 2018 after reportedly suffering from colorectal cancer.)

Throughout it all, Mugabe remained popular among his fellow African leaders, frequently railing against the West for interfering in Africa’s affairs and denouncing homosexuality. In 2014, he was elected as the Chairperson of the African Union.

Shiraaz Mohamed / AP

But ZANU-PF’s internal struggles caused the party to deteriorate as party leaders grew fearful that Mugabe would hand over power to his wife, Grace. In September 2017, Mugabe abruptly fired Mnangagwa, then Vice-President, saying that he had been disloyal to the party. Mnangagwa was popular among military leaders, and his firing ignited a response that would eventually lead to Mugabe’s downfall.

On Nov. 15, 2017, the army took over state television and announced that it had placed Mugabe and Grace under house arrest, noting unrest within ZANU-PF and warning that the military would intervene in order to protect the country. The party then gave him an ultimatum: Resign by Nov. 20, or be impeached. Zimbabweans across the country flooded the streets, demanding that Mugabe step down.

The following day, the embattled leader interrupted the impeachment process that ZANU-PF had initiated in the legislature and submitted a letter announcing his resignation.

“My decision to resign is voluntary on my part and arises from my concern for the welfare of the people in Zimbabwe and my desire to ensure a smooth, peaceful, and nonviolent transfer of power,” the letter read.

Mugabe went into hiding, but reemerged in March 2018 with his first televised interview since stepping down, claiming that Mnangagwa, now serving as interim president, had seized power illegally.

“He was assisted by the army. I said it was a coup d’etat,” Mugabe said, adding that Zimbabweans “have not experienced such an environment before. We’ve prided ourselves on being very democratic.”

In July 2018, Zimbabweans elected Mnangagwa president in their first election without Mugabe on the ballot, although the poll was again rife with allegations of voting irregularities from the opposition. Zimbabwe has also seen internet blackouts and periods of civil unrest this year.

Mugabe is survived by his wife, Grace, and his children Bona, Chatunga, Robert Jr., and Michael.