This is the case in parts of Africa where the legacies of colonialism, ethnic rivalries, corruption, continued outside meddling and geography have combined to create states with little to glue them together and much to tear them apart.

Last week’s military coup in Gabon against President Bongo featured some of these underlying causes. Others, such as in Mali, have them all.

Corruption and poor governance exist in many parts of the world but because of the exacerbating factors outlined above, Africa is more vulnerable than other regions.

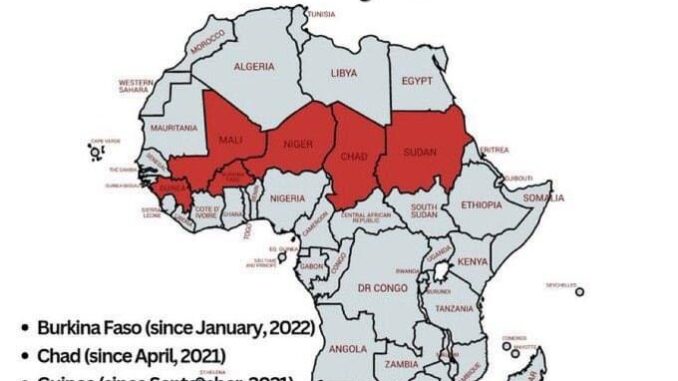

Since 1950 there have been more than 480 coup attempts globally and almost half of them have been in Africa, of which over 100 succeeded, according to data compiled by the American researchers Jonathan Powell and Clayton Thyne.

Forty-five of the 54 nations across the African continent have experienced at least a single coup attempt in the same time frame.

Seventeen of the 18 coups worldwide since 2017 have been in Africa and the majority have been in west Africa and the Sahel.

After each military takeover there are calls from other countries for a “return to democracy” but rarely an admission that what was overthrown was typically far from democratic. Displays of support for the coup from sections of the public are often dismissed.

In the case of Gabon, the family of the deposed president had ruled the country since 1967 via a series of fraudulent elections followed by brutal repression of opponents. Hundreds of members of the Bongo clan took the top posts in government and major companies and were given immunity from prosecution. They pillaged the country for 55 years. The country’s oil reserves bring in billions of dollars each year and yet there is widespread poverty. Little wonder, then, that there was dancing in the street at news of the coup even as the UK condemned the “unconstitutional military takeover”.

There, as in other Sahelian countries, the government’s writ runs out when the concrete does, and rural areas receive little to no help from central government. This was among the contributing factors in the Malian coups of 2020 and 2021.

The Sahel is particularly prone to coups because of its geography. The region is semi-arid, has poor crop growth and suffers water and food shortages. Climate change is increasing the desertification of northern regions, which now blend into the Sahara desert. All have huge ungoverned spaces and massively expanding populations, with few opportunities for young people. Some of the countries are landlocked, all are corrupt, rich in resources but with impoverished populations. It is a recipe for combustibility. Any government that cannot bring security risks being overthrown by senior military officers, many of whom are themselves busy in the corruption business and who realise they could get more of the action if they were in charge.

History is also a major contributing factor.

In Mali, the lighter-skinned Tuareg peoples of the north had been fighting the darker-skinned Bambara from the middle Niger valley for centuries. The Bambara, and other groups, had never forgotten the Tuareg’s role in the Arab slave trade. Now they were both told they were in the same nation. It took just two years before the first Tuareg rebellion broke out to create a separate state.

Sporadic violence continued through the decades but exploded after the western-backed overthrow of Libya’s Colonel Gaddafi in 2011. Gaddafi had hired thousands of mercenaries for his “Islamic Legion”, many of them Tuaregs from Mali, Niger and Chad. His demise caused them to loot their bases and return home carrying heavy weapons. A year later another Tuareg rebellion broke out in Mali, with al-Qaeda and Islamic State involvement. Timbuktu, a historically important centre of Islamic culture in the north of the country, was captured, and so French troops were invited to help government forces.

The rebellion was beaten back but instability grew and intercommunal violence spread across to the Mali-Niger border and down as far as Burkina Faso, which had its own coup last year. The Malian government’s inability to protect its people led communities to form militias, which helped to create the conditions for a coup in 2020.

After seizing power it is easy for the new junta to broadcast to the people about how it has stepped in to put an end to brazen corruption. The population may not believe it, but that doesn’t mean they’re not pleased to see the back of the previous rascals. The military leadership can then ignore the template denunciations from the relatively toothless African Union and Economic Community of West African States.

Not all coups involve surrounding the presidential palace and arresting the leader. In 2021, Chad experienced a “dynastic coup”. After the death of President Déby, the army simply declared his son “interim president”. France, conscious that Chad hosts French troops, said the military takeover was justified for security reasons.

France may have gone through the motions of hauling down its flag as independence spread across the region, but it engineered ways of maintaining enormous influence. The key was the CFA franc — a currency that deprived countries of monetary sovereignty. Governments were required to deposit half of their foreign reserves in Paris, while trade deals were enforced benefiting French exports. The CFA was only retired in 2020.

Also retiring (hurt) is most of the French military mission against jihadist insurgencies in the region. At its height there were 5,000 French troops deployed at the invitation of five Sahelian governments, but after the coups in Mali and Burkina Faso they were told to leave and their position in Niger is now uncertain. Since 2012 France has spent roughly €1 billion a year on the operation. The human cost has also been high with 59 French soldiers killed, 52 of them in Mali.

Last week President Macron described the operation as a success, telling Le Point: “They have prevented the creation of caliphates a few thousand kilometres from our borders”, and arguing that without intervention, Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger might no longer exist. Either way, French policy is now severely damaged, and public opinion at home has turned against further military involvement.

This history is why coup leaders can easily portray an overthrown president as a puppet of France, as happened in July in Niger, where the coup was quickly followed by an attack on the French embassy. The new leaders may or may not throw out French and US troops and invite in the Russians, in the form of a Wagner-type group of mercenaries. It depends on who makes the better offer.

Either way, life is unlikely to improve after a coup for ordinary people there or in Mali or elsewhere. The riches to be earned from uranium, iron ore and bauxite will not reach them. The French forces deployed in several countries were insufficient to suppress insurgencies. If Russians replace them, it will be only to safeguard the capital and guard the latest dictator in the presidential palace from the next coup attempt or attack by terrorist groups. A UN report this week said Islamic State had doubled the Malian territory it controls in under a year. The “state” will not protect the people, so why should they have allegiance to it?

• Meet Gabon’s new leader: Ali Bongo’s cousin takes control after coup

It is important to emphasise that most African countries, especially those with growing economies, do not suffer frequent coups, but the vast region stretching from Sudan to the Atlantic is becoming an exception and is now in danger of becoming a sea of unstable military dictatorships.

Coups are contagious and a host of countries on the Atlantic coast risk being infected. The legacy of colonialism and continued foreign interference is in the dock, but the political and military classes in the Sahel and elsewhere must also take responsibility for their failures and for their greed.