By Gary Schulze

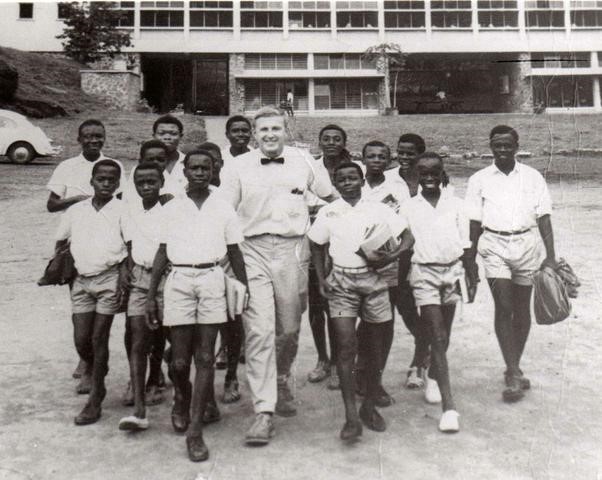

I came to Sierra Leone as a young Peace Corps Volunteer in 1962 and was assigned to teach history and civics at the Albert Academy in Freetown. It was shortly after Independence and a spirit of nationalism permeated this newly-born African nation. After teaching Forms I and 2 history and civics for a few months, I was asked by the Principal, the legendary Max Bailor, to introduce Sierra Leone History into the school’s curriculum for the first time. Until then, the schools in Sierra Leone taught only European and Ancient History. In preparation for this, I read everything I could about the country and soon realized that one important person I would have to emphasize in my history classes was the famous warrior Bai Bureh, a household name throughout the country since 1898. Little did I know then what an important role he would play in my life for the next fifty years.

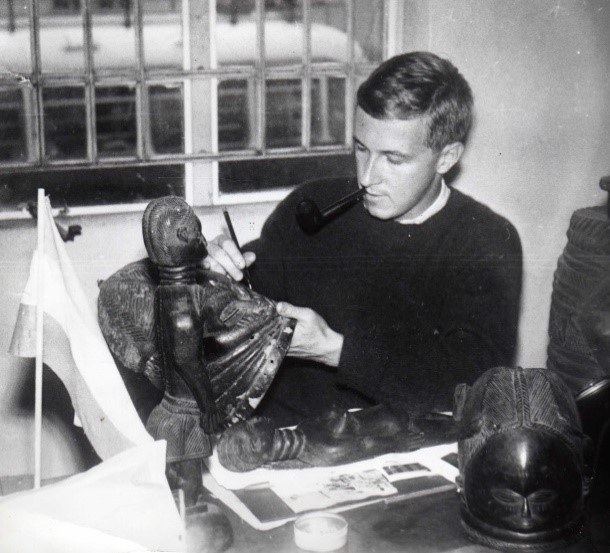

At the Sierra Leone Museum, 1963

With Form 1 students at Albert Academy, 1962

Bai Bureh was the ruler of a small Temne chiefdom called “Kasseh”, in what is now Sierra Leone’s Northern Province. He was sent as a young man to Gbendembu, a training school for warriors where he earned the nickname “Kebalai”, meaning “one whose basket is never full” or “one who never tires of war”. He opposed Britain’s declaration of a “Protectorate” over the interior in 1896, and the tax levied on the houses of the native population. In addition, the British Governor, Frederic Cardew, wanted to reduce the power of the African Paramount Chiefs by appointing white District Commissioners. When war broke out over these issues in 1898, Bai Bureh led a coalition of fighters from several different kingdoms in a brilliant campaign that took the British entirely by surprise. When the British offered a reward for his capture Bai Bureh responded by offering twice as much for the capture of the Governor. Using classic guerrilla tactics and warriors equipped with only muskets, swords, spears, and slings, he held the British forces at bay for several months. But when British soldiers began burning the food supplies of the villagers who supported him, Bai Bureh was forced to surrender. By then he had won the admiration of his adversaries for both his fighting skills and his protection of civilians caught in the war zone, including British, American and Krio missionaries. So, after he surrendered, saying, “Me nar Bai Bureh, de war done done”, the British accorded him great respect, taking him into custody but allowing him some personal freedom during his captivity at Ascension Town in Freetown, and later in the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) where he was exiled for seven years. The British would eventually bring Bai Bureh back to Sierra Leone and reinstate him as the chief of Kasseh where he died and was buried eight years later.

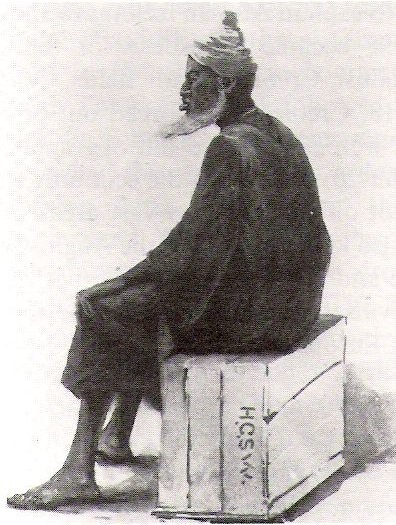

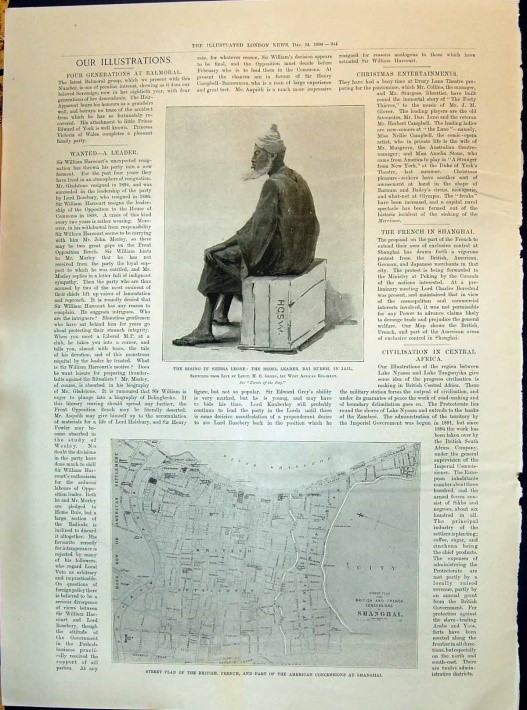

While Bai Bureh was under house arrest in Ascension Town, a British Lieutenant in the West Indian Regiment, Henry Edward Green, made a pencil drawing of the great warrior depicting him sitting sideways on a wooden box looking like an angry, despondent, shoeless old man, with a ronko draped over his slumped shoulders. The drawing was published in the London Gazette in 1898 alongside a dispatch from Freetown describing how “the petty chief” Bai Bureh and his followers had been roundly defeated by British troops, thus successfully ending the rebellion in the Protectorate of Sierra Leone.

Green’s drawing and the London Gazette, December 24, 1898

For more than 100 years after Bai Bureh’s death, Lieutenant Green’s drawing was still the only known contemporary image anyone had ever seen. This image was reproduced throughout the country. It appeared on postcards and in school history textbooks. In the 1960’s, Freetown carvers began making Bai Bureh statues based on Green’s pencil drawing in various sizes for sale in the markets, along with decorative wooden wall hangings with the warrior’s image. Paintings appeared as well, some presenting him as a king sitting on a throne holding a sword surrounded by people he had captured. The Green image became the logo for Bai Bureh Hospital, the Bai Bureh Warriors, a major soccer team, and it appeared on walls of buildings all over the capital, including the Paramount Hotel and the Ministry of Tourism in Freetown.

Primary school students in Sierra Leone were often taught a song aimed at debasing Bai Bureh:

Bai Bureh was a warrior

Who fought against the British

The British made him surrender

He shouted Khortor Maimu

Khortor baykitor

He hollered Khortor Maimu

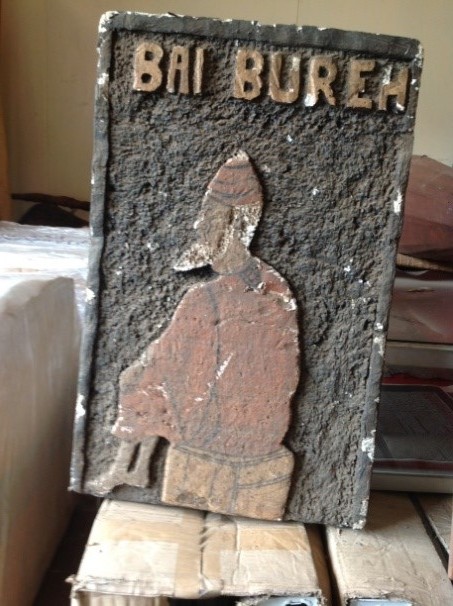

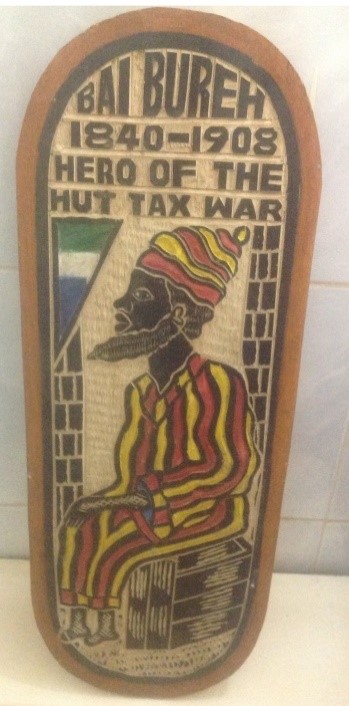

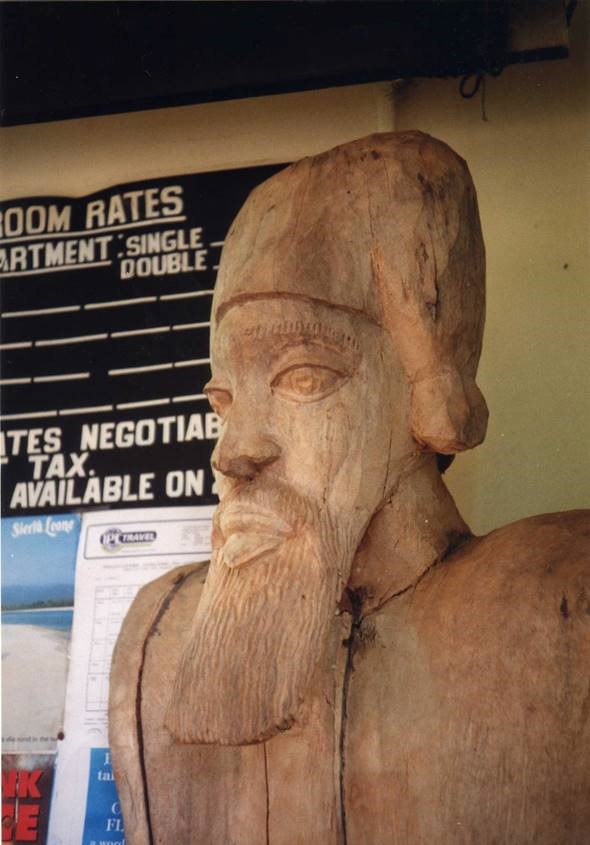

Various carvings and paintings of Bai Bureh based on Lieutenant Green’s drawing

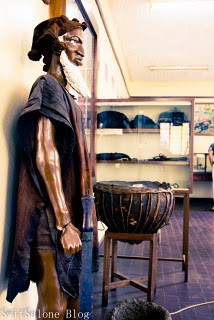

Several months after arriving in Sierra Leone, at the request of the Foreign Minister, Dr. John Karefa-Smart, the Peace Corps transferred me to the National Museum, at the old Cotton Tree Station, where I worked As Acting Curator under the direction of Dr. M.C.F. Easmon and served as Secretary to the Monuments & Relics Commission and the Museum Committee. I thought it would be interesting if we could come up with a statue of Bai Bureh that school children could come to see in the museum to get a better understanding of the important role he had played in their country’s history. I commissioned Mr. J.D. Marsh, a well-known maker of cemetery monuments who lived on Sankey Street, to make the statue. I gave him a copy of Lt. Green’s drawing and told him I wanted a three-dimensional, like-sized statue based on the picture. After examining it carefully, Mr. Marsh asked me the obvious question – What did Bai Bureh look like from the front? I told him we had no idea and that he would have to use his imagination to come up with the best face he could from the profile view. I agreed it was not much to go on, but at least he had a life portrait to work with.

Two weeks later Mr. Marsh sent a runner to tell us the figure was finished. Together with two museum assistants, I went to his workshop near Congo Market and we carried the statue up a steep hill to an awaiting taxi. The figure, painted in flesh colors and wrapped in a country cloth, looked so realistic that people passing by thought they were witnessing a white man and two Africans carrying a corpse up the hill. Several elderly women began wailing and clapping their hands.

Once we got the statue to the Museum, I unwrapped it to see how good a job Mr. Marsh had done portraying the face. My expectations were not high since he was working with very rough materials – basically just plaster laid over a wire frame. The result was pretty much as expected. The Marsh creation was more a manikin than a sculpture, and more a caricature than a portrait. The face had oversized, heavy-lidded eyes, typical of Yoruba sculpture (Marsh was a member of local Krio hunting society). But it bore enough of a resemblance to Green’s pencil drawing to look familiar to Sierra Leoneans, and it had the advantage of being life-sized.

Mr. Marsh’s Statue of Bai Bureh

Close-up showing The Cap

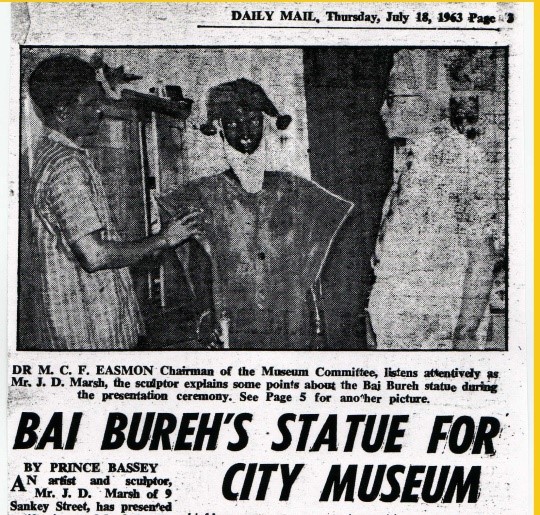

Daily Mail, July 16, 1963

I dressed the figure in a large “ronko” or warrior’s gown from the Museum’s collection characteristic of Sierra Leone’s northern tribes. But the hat was a problem. In the pencil drawing, Bai Bureh is wearing a white cone-shaped hat. We had nothing like that in the museum so instead I reached into a bag of hats and found one made from the same rust-colored material as the ronko. Although it had a very different shape, with three points each ending in a tassel, I placed it on the statue’s head. Then, to complete the statue, I wired an antique sword dating to the period of the Hut Tax War to the figure’s right hand.

The Daily Mail newspaper published an article about the statue with a photograph of Dr. Easmon and Mr. Marsh standing next to the figure, and SLBS covered the story as well.

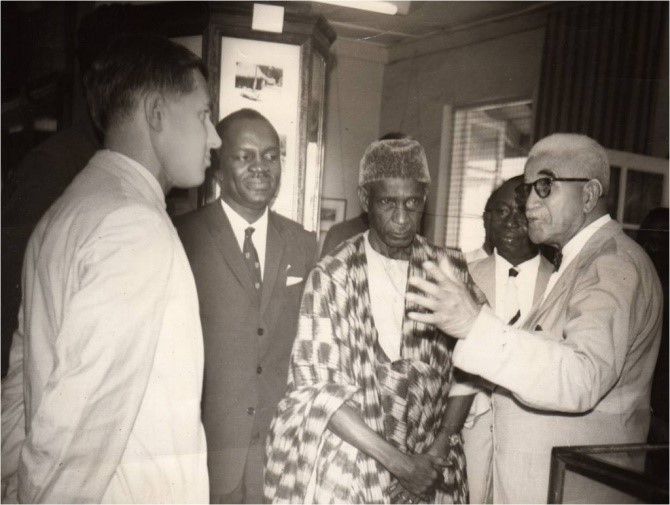

Sir Milton Margai, Dr. Easmon, Dr. Davidson Nicol, Amadu Wurie and Gary Schulze at the Museum, 1963

Over the next few months, thousands of people came to the Museum to see Bai Bureh’s statue, including the Prime Minister, Sir Milton Margai, and the Governor-General, Sir Henry Lightfoot-Boston. Mrs. Cummings, who had succeeded Doctor Easmon at the Museum, recalled that in the late 1960’s, Bai Bureh’s aged granddaughter led a group from Kasseh on a pilgrimage to Freetown just to view the new statue. People frequently wandered in to gaze at the chief, sometimes putting their hands to their chins, and sighing, “Ah, Bai Bureh, Ah Bai Bureh.” Mrs. Cummings remembered that when the statue was near the front entrance of the Museum, it was common to find to find a medicine man kneeling on the floor arranging fetishes before the ronko-clad figure, whispering incantations.

Schoolchildren viewing the statue at the museum in the 1980’s.

Bai Bureh metal placard on the front gate of the museum, patterned after the statue.

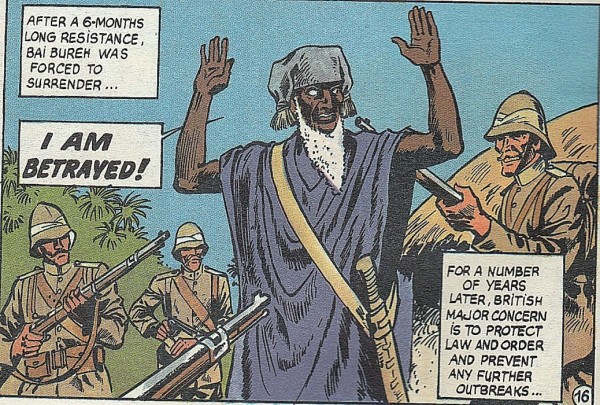

In the years that followed, long after I had returned to my home in New York, the statue took on a life of its own. Photographs of the figure began to appear in Sierra Leone history books and tourist brochures and when President Siaka Stevens hosted the OAU Conference in 1980, a souvenir booklet was printed featuring a photograph of the statue with the caption, “Bai Bureh, 1840-1908.” Then, when Stevens was leaving office, he commissioned a company to produce a colorful, hard-cover comic book on Sierra Leone history. The artist portrayed Bai Bureh in a fighting mode wearing both the ronko and the tricorn hat that I had dressed him in, swinging his war sword over his head as he charged into battle. The comic book completed the process by which Marsh’s statue had become the iconic image of Bai Bureh.

From “Once Upon A Time…Sierra Leone & A President Called Siaka Stevens”, 1984

In October 1993, thirty years after completing my Peace Corps service, I returned to Sierra Leone to visit old friends and to see what changes had taken place in the country during the interim. Dr. Easmon had passed away many years earlier and Sierra Leone was now in the midst of a brutal civil war. I went to the Museum my first day back, and there, to my surprise, was Marsh’s statue still standing proud, although some of the paint had peeled off the nose and the right arm was broken, with wire and plaster hanging from where the sword was attached. Mrs. Cummings told me the figure had been damaged from being dragged around to various agricultural shows over the years.

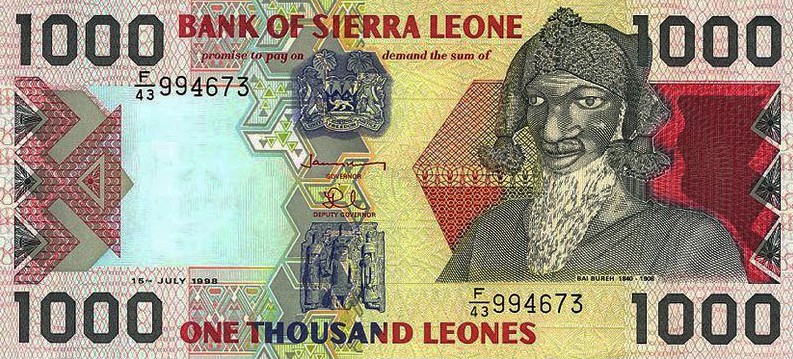

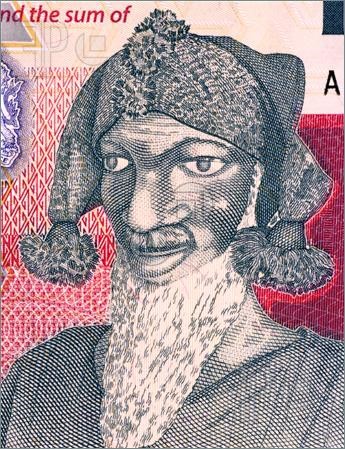

The following year, the Bank of Sierra Leone issued new currency – a red Le 1,000 note featuring the face of the Museum statue, with the doll-like face, tricorn hat and tassels. Beneath the picture were the dates of his birth and death. The banknote even showed the missing paint on his nose. The statue had become the accepted image of Bai Bureh.

Local artists were now making wooden replicas of this statue, just as they had with Lieutenant Green’s pencil drawing. The figures came in various sizes and were just as stiff and straight-backed as the original, with the sword placed awkwardly in front. All of them had the same tricorn hat with tassels like the one in the museum. Some were even dressed in country cloth gowns. There were also gigantic versions of the statue standing in the lobbies of the Mammy Yoko and Bintumani hotels in Freetown. Hotel workers were heard telling tourists that these carvings were very old and very traditional. By 1994 vendors were even selling “Mrs. Bai Bureh” carvings to go with “The Chief.” And some people who visited the Museum over the years were told by staff that the hat actually belonged to Bai Bureh.

Carvings based on Mr. Marsh’s version of Bai Bureh

Around this time I began corresponding with the well-known historian and anthropologist Joe Opala who had also worked at the museum some years after I had. He sent me a paper he had written on the evolving “Image of Bai Bureh” and pointed out that my choice of a hat for the statue was a big mistake. Joe said that particular hat is worn in Sierra Leone by only three tribes – the Koranko, Yalunka, and Limba – and only by special hunters who have killed three elephants, leopards, or bush cows (buffalos). Bai Bureh, on the other hand, was affiliated with two entirely different tribes – the Loko and Temne. He was born and raised a Loko. His mother was a Temne and he ruled a Temne kingdom at the invitation of its people who were impressed with his military skills. Joe insisted there was no possibility that Bai Bureh had ever worn a hat used by tribes other than his own.

A giant statue at a Freetown Hotel and a close-up of the buffalo hunter’s cap I put on the figure.

Opala was fascinated by the way the Museum statue had become so deeply fixed in the popular mind and he predicted that the new version of the great warrior would gradually replace the old one. I shared his fascination with the way Bai Bureh’s image had evolved over time but felt somewhat guilty for having chosen the wrong hat. It was upsetting to think that I had misinformed Sierra Leoneans about their greatest hero, however unintentionally. Yet the icon I helped create was becoming so powerful, there seemed to be no way to correct the mistake.

Opala tells the story of the time he gave a public lecture on Bai Bureh’s image at the German Embassy in Freetown. Joe pointed out to the audience of young artists how a Peace Corps Volunteer named Gary Schulze had chosen an inaccurate hunter’s hat to put on the statue’s head. When he suggested they revise their image of the warrior, a young poet marched up to the podium and objected. “My grandfather”, he said, “told me that Bai Bureh wore the hunter’s hat.” Their Bai Bureh, Joe said, had to be a man of power and the ordinary Muslim elder’s hat (in Green’s drawing) simply would not do. He was told by another older Sierra Leonean, “You’ve just got to understand, for most people, that museum statue is Bai Bureh.”

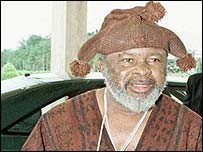

When civil war broke out in Sierra Leone in the 1990’s, the RUF rebel leader, Foday Sankoh, began wearing a cap identical to the one I put on the statue’s head, perhaps to identify himself with Bai Bureh and make people believe he had somehow inherited the warrior’s powers. Similar hats were also worn by some of the RUF’s foes, the Kamajors. When the war ended, the government built a large Sierra Leone Peace & Cultural Monument next to State House to celebrate the country’s history. Included in the permanent exhibition is a giant mural showing Bai Bureh wearing that same tricorn cap with tassels that I mistakenly gave him thirty years earlier.

The RUF leader Foday Sankoh

The Peace & Cultural Monument near State House

It always puzzled me that no one had ever seen an actual photograph of Bai Bureh, especially while he was under house arrest in Ascension Town. The local press reported at the time that hundreds of people gathered in front of the captured warrior’s house every day to catch a glimpse of him. Those crowds probably included some of the prolific Krio photographers working in the city at the time, such as the Lisk-Carew Brothers and W.S. Johnston. They all had studios in Freetown and were already taking pictures of other famous Sierra Leoneans including Paramount Chiefs Madame Yoko and Kai Londo. In addition, the British military and colonial community in Freetown included many amateur photographers. I believe there can only be one explanation for the absence of photographs. While I have no solid evidence to back this up, I suspect there may have been a strict prohibition against anyone taking Bai Bureh’s picture, perhaps subject to arrest or, in the case of the military, to court-martial proceedings. The British Governor certainly did not want to see Bai Bureh promoted as a symbol of African resistance to British rule. He must have been quite satisfied with Green’s drawing of the defeated old man sitting on a box, an image that would be instilled in the minds of generations of Sierra Leoneans to come.

As the years went by I began to search for an actual photograph, convinced that one had to exist somewhere. When the internet appeared in the 1980’s, my search area grew vastly larger. Then, on 12 August 2012, 108 years after Bai Bureh’s death and 50 years after Mr. Marsh made the statue based on Green’s pencil drawing, an incredible thing happened. A photograph of the great warrior appeared on Ebay, the internet auction site. I was contacted by an old friend, William (Bill) Hart, who has done extensive field work in Sierra Leone and is an authority on the history and cultures of the counry. Bill had also seen the picture and was excited about the prospect of us acquiring it for the people of Sierra Leone.