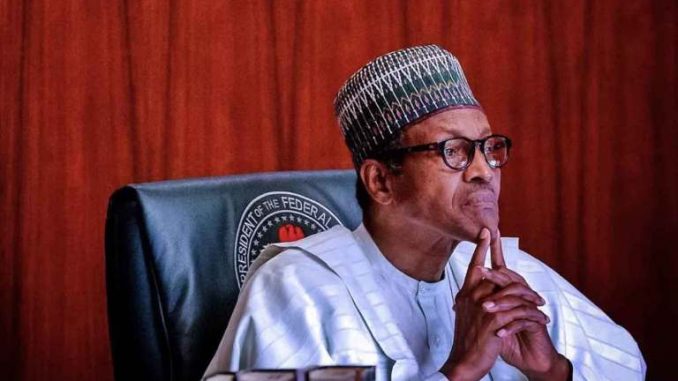

When Muhammadu Buhari won Nigeria’s presidential election in 2015, his victory was met with excitement and hope.

Voters were taking a chance on the retired Nigerian army general who had previously served as head of state from December 1983 to August 1985 after taking power in a military coup d’etat.

- Buhari and his All Progressive Congress (APC) were given the keys to the country, following uninterrupted rule by the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) for nearly 16 years since the re-installation of democratic rule in 1999.

- But the excitement around his 2015 election fell flat in the face of the collapse in prices of Nigeria’s main export, oil, as the country fell into recession in 2016.

Most political analysts expected the re-election of Buhari in 2019 to signify stability and re-ignite business in the country. But nearly eight months after the election, economic growth has drastically slowed to 1.94% in the second quarter of 2019, which is the second straight quarter of declining growth numbers for the country.

- The Nigerian economy grew 2.1% in the first quarter of 2019. The Central Bank is still forecasting 3% growth for 2019 for Africa’s largest economy. Yet the feeling on the ground and behind closed doors is 3% may be the upside for Nigeria in 2019 with a downturn expected in 2020.

And many are fearing a repeat of the recession that followed Buhari’s first term of office.

Why the Fears of Recession?

First, Africa’s top oil producer remains heavily dependent on oil, with crude accounting for 90% of foreign currency earnings and nearly 70% of the government’s income.

- Low oil prices and falling output in 2016 underwrote Nigeria’s economic recession in 2016.

- Prices remain low at sub-$60. The recent bombing in Saudi Arabia showed that prices can be disrupted for only short periods with oil producers, with markets ready to respond to shocks (and consequently keep prices low).

- With production costs around $25 to $35 per barrel in Nigeria and Brent crude offtake prices ranging from $50 to $65 per barrel in the country, many producers will barely make profit, particularly in scenarios where overhead is high and debt payments weigh down cash flows (all of which is par for the course in Nigeria).

- Nigeria is also confronting ageing oilfields and lack of new investments.

- An uptick in exploration projects does not necessarily spell a boost for output considering the typical timeframe from exploration and development to production.

- A new exploration sadly may not hit the market until late 2022 or in 2023. Security will also remain an issue in the Delta and beyond. Terrorism sadly continues to disrupt production in the country and raises the cost per barrel for any producer.

Second, Nigeria non-oil sector growth is still relatively slow with approximately 1.6% and 2.6% growth respectively in the first and second quarter of this year, according to the Nigerian statistics office.

- The reality remains that Nigeria’s manufacturing, retail, and banking sectors face structural problems that Nigerian politicians struggle to fix (irrespective of the party in control). For example, electricity shortages have stunted the maturation of the manufacturing and industrial space in Nigeria.

Third, liquidity in the banking sector is undercutting growth and investment. Banks are increasingly reluctant to lend to the private sector with inadequate access to finance undercutting economic growth.

- The Central Bank fined 12 banks more than NGN 400 billion ($1.3 billion) for failing to meet its minimum loan-to-deposit ratio requirement of 65%. The banks fined include First City Monument Bank, First Bank, Guaranty Trust Bank, United Bank of Africa, and Zenith Bank.

- Most banks reduced lending following the recession in 2016 and the oil price crash in 2014. Officials’ urgency to pump cash in the economy via lending is understandable and appreciated.

However, an overly quick rebound in lending to the market could easily backfire with loans flowing to low quality assets (to meet loan-to-deposit requirements) and weakening the bank balance sheets of banks in the country.