by Titus Boye-Thompson

Literary critics generally agree on the necessity for cultural productions to be grounded in identifiable geographical (topographical) landscapes. Edward Said’s article “History, Literature and Geography,” which provided an analysis of Antonio Gramsci’s works posits that “all ideas, all texts, all writings are embedded in actual geographical situations that make them possible.”

This relationship is exacerbated in an Africa where landscapes are imbued with social significance. Mountains and Oceans are rarely considered in this isolation because of the impossibility of their vastness and the improbability of human foray into their innermost reaches but streams, forests and slow flowing rivers are given spiritual powers leading to what Taylor (1969) refers to when he connotes that “the historical background, social customs, religions ideas, political aspirations and a variety of other factors aspects of the environment are as significant as soils, climate and natural vegetation.” . Wa (1997) corroborates this when he says that “what form(s) the African sensibility, [cannot] be divorced from the landscape and the historical experience.”

Cheney-Coker (1990) parades Sierra Leone in his poetry as his proximity and rootedness in the landscape offers a pin pointing of the landscape and the ruggedness of the topography as a brush to paint out his aggressiveness and loathing of his self angered venting. His seminal work, “The graveyard also have teeth” is, like Koroma’s work, split into two parts but as Koroma runs his thematic across his work, the context of nostalgia straddles the tome whilst Coker exhibits a love hate relationship as a display of dichotomy and opposites.

He states his position implicitly as he contends that his has been an existence of continuous struggle to belong. In his poem, “the Heart,” the Poet states “My country you are my heart,” to delineate the sanguine nature of the relationship with his place of origin and combining that with the intimate relationship that his memories evoke and the longing for a juxtaposition of love, care, pain and even dissatisfaction that kills the Poet’s soul; as the ravages of conflict and tensions, politics and deceit distances him from his homeland. he states his desire thus;

I who have so loved and hated you

My country

I want to be your national symbol of life

Coker, like Koroma reflects on being a poet in Sierra Leone when he contends that “poetic duty is defined. The poet’s role in his country is crucial, in the sense in which he has the onerous task of reminding the country to constantly examine itself and live up to its image in the context of Africa and the world.”

The first impression of Koroma’s work fills you with the Poet’s unyielding love of his place of origin and his unashamedly acute desire to return to where he feels most comfortable and at peace. This view is buttressed by a notable sociologist and friend of the Poet in his foreward, as he quotes his first lines from the tome;

We remain loyal to this part of town

We impatiently await the eerie moment

The sense of loss, estrangement and disconnect from his childhood haunts and the playgrounds of a buttered youth rings a pleasant melancholy from the poet’s pen as he unleashes the sombre soliloquy of a return to those days of security, to the pleasant safety of pre-birth and nascent abandonment of responsibilities to pay the bills and bring home the bacon in a competitive and cut throat industrial economic complex characterised by a working environment in chemistry and industry.

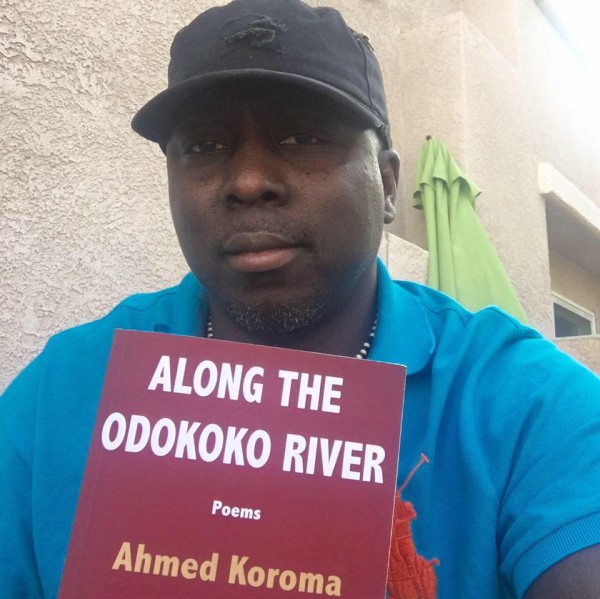

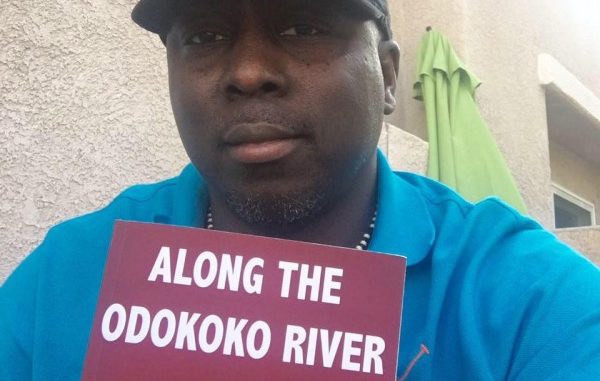

“Along the Odokoko River,” is a myriad rendition of a yearning to return to a place of origin, delivered through a nostalgic recount of a past glory, a celebration of a lived experience for the Poet in a Freetown that still showed promise. It sends out the hope of return, a recurring theme throughout, encapsulated in the lines of the first poem, “Freedom” thus;

For later I will pluck my wings and retire well

Into the night, with those who have walked this path

Some would easily recount the historical context of Freetown, a former British Crown Colony as a backdrop of any work of art, especially in the communicative art, symbolistic of the need to vent out the slavish imprimatur of colonialism and the downward backwardness of native discourse yet to succumb to such nihilistic tendencies would be fatal and intellectually obtuse. The need for contemporaneity necessitates a review of more assiduous study of the changing perspectives of the Poet’s surroundings and not to the vainglory of a time long past and only recalled by folklore and pilgrimages of the mind. The splitting of this volume into two parts organized the Poet’s work structurally and thematically. In a poignant note, the Poet symbolizes his personal circumstances by adjoining the theme of a return of love and lust. His is a life of second chances, especially in love and romance and thus when he says in the Poem, “Soliloquy”

So as I lust for your return

And refuse the curtain call

While I anticipate a much needed encore,

He is sending a vaunted plea to a loved one that,

It is with assorted emotions

That I continue to wait by the shore

This poem is set in context by the Poet going back to the place of his contentment, the river ‘shore’ but only after having done enough to guarantee that his pleas of reunion are not in vain. The continuation of this story also evokes the split nature of the Poet’s love life, the ‘before’ and ‘after phases’ of an estranged relationship that eventually culminated in wedlock.

“Easter” sets another scene though as in keeping with the theme, the kites are anchored even as they fly up into the air. The loss of a kite is always a reason for blame, a charge of careless abandonment and immaturity leaves the loser dejected. The Poet extends a proximate sincerity of the context of the crossing of religious boundaries that typifies social engagements in Freetown. He being Muslim would easily evoke a critically Christian celebration of kite flying at Easter is indicative of his lived experience and grounding in the locality. However, the initial decision to depart from these shores is regretted in the thrust of his writing but Easter depicts the yearning that once caused this action to be enabled. Going away was the only way to scale heights and reach for the sky and the regret is only vested in the possibility of the potential for the kite’s thread to be cut and the kite lost for ever in some distant land that it would one day come to rest.

When we silently wish we could fly away in zest

We let our kites sail through the evening instead

The Poet uses myths and folklore to expand his story telling. The incantations of Ogun, the mention of Shai’tan combine to augment a centrality of myth that hinges on the universality of literature in the African experience. The Yelibas and Griots would offer flowery tales of men and animals in distant places and with the powers of Gods more amply foretold. In such depictions, the Poet conveys what Carl Jung calls the ‘collective unconscious.’ However, for myth critics like Maud Bodkin and Northrup Frye, “history is inconsequential since mythopoetic experiences generally reveal myths as timeless or eternal.”

Because we are told to shut our little eyes

And silently recite Surat al ikhlas seven times

Lest Shai’tan snatches away our little hearts

The Poet follows Wole Soyinka in “A Dance of the Forests” to laconically “attempt to convert historical circumstances through the enactment of ritual in order to create societies freed from the archetypal burdens of tyranny, corruption and moral decadence.” In his rendering of war and society, he uses the historical contexts as backdrop for what he sees as a recurrent imagination, of societal values following a historical degeneration into anarchy and the fragility of the vaunted truths of constitutionality, peace and freedom.

The relic of the war remains with us

So we whitewash the bloodstained walls

As he introduces this concept of retrogression he leads the audience on to the plight of his river, now strained by over population and its vices, the strain on its sinews as its flow ebbs, but the constancy of the change leads only to damnation and anarchy.

And slowly reveals the patched cracks

Catapulting all of us back to our very past

Koroma enjoyed a wholesomeness of safety at a time when his country was in turmoil. The creation of a cyber reality provided for him a virtual family of like-minded ‘exiles’, plunged into war that was remote to their consciousness and blighted any commonality of understanding of suffering as the ravages of foreigners encourages kith to turn against kin. He had no choice but to become part of Leonenet, “a diasporic communicative space where Sierra Leone’s state-related symbols were generated and then held in conceptual escrow, waiting for the institutional structure to return.” Tynes (2007). This return has now prompted two volumes of poetry, this tome “Along the Odokoko river” being the second in the series.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Bodkin, M. (1978) Archetypal patterns in Poetry. Oxford University Press

2. Cheney-Coker, S. (1990) The Blood in the desert’s eyes. Heinemann

3. Frye, N. (1968) The archetypes of literature in Vickery, J. B. ed (1968) Myth and literature: contemporary theory and practice. University of Nebraska Press

4. Jung, C. G. (1966) Modern man in search of a soul, Routledge

5. Taylor, F. D. S. (1969) Research in rural geography,” in Miller, N. N., ed. (1969) Research in Rural Africa. Canada: Canadian Journal Of African Studies, pp 272-275

6. Said, E. W. (2003) Reflections on exile and other essays.: Harvard University Press,

7. Tynes, R. (2007) Nation building and the diaspora on Leonenet: a case of Sierra Leone in cyberspace. New Media and Society 19(3) pp 497-518

8. Wa, T. N. (1997) Writers in politics. A re-engagement with issues of literature and society. James Currey