Gallery

But now the fighting appears to have become a move to overthrow the government, or at least significantly weaken its ability to rule large portions of the country.

Kiir and Machar “are very different men, with very different kinds of political instincts, and a very different standing with both the body politic of Sudan and, until recently, with the [army],” said Eric Reeves, a well-known analyst on South Sudan and a professor at Smith College in Massachusetts. Given the ethnic diversity within the army, he said, “the events of the last days were, if not inevitable, all too likely.”

The men’s rivalry reflects the turbulent path South Sudan has taken to independence as well as the country’s uncertain political and economic future. Its people have endured one of Africa’s longest civil wars. Violent infighting split the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) in the 1990s. Since independence in 2011, political, ethnic and tribal rifts, along with growing corruption, have hindered the development of a unified national identity.

“What we are seeing in South Sudan is the convergence of two parallel conflicts that have been developing over time,” said Douglas Johnson, author of “The Root Causes of Sudan’s Civil Wars.” “One is the emergence of an internal opposition within the political party of the SPLM. The other growing conflict is within the army.”

Machar has made it clear that he wants Kiir ousted. “He must go, because he can no longer maintain the unity of the people,” Machar told the French broadcaster RFI on Thursday, speaking from an undisclosed location. “Especially when he kills people like flies and tries to touch off conflicts on an ethnic basis.”

The rivalry between Kiir and Machar stretches back more than two decades. Kiir is from the Dinka, South Sudan’s largest tribal group, while Machar is from the Nuer, the second-largest. They rose through the ranks of the SPLM and its armed wing in very different ways.

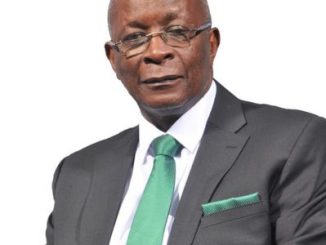

Kiir, who is 62 or 63, was a guerrilla commander in the 1960s in Sudan’s first civil war. As part of a 1972 peace pact, he was absorbed into Sudan’s national army, reaching the rank of major. In 1983, Kiir joined a second rebellion and helped found the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), which fought the Khartoum government for more than two decades.

For much of his rebel life, Kiir worked in the shadow of John Garang, a charismatic leader and fellow Dinka who died in a 2005 helicopter crash shortly after becoming first vice president of Sudan and months after helping negotiate a peace deal to end the second civil war. Kiir became the SPLM’s leader and assumed the post of first vice president.

Known for his blunt speech, Kiir proved to be a deft political operator. He ensured that Khartoum held up its end of the peace deal, which paved the way for South Sudan’s independence. While other SPLM leaders, including Garang, sought greater rights for southerners in a united Sudan, Kiir had always wanted independence.

Those who know Kiir describe him as humble, honest and meticulous. Some say he is a reluctant leader, forced into his role. They disagree with Machar’s statements that he is autocratic.

“He is a consensus-builder,” said Luka Biong Deng Kuol, a South Sudan expert and a fellow at Harvard University’s Carr Center for Human Rights Policy. “I did not see in him a dictatorial tendency. He is not so keen on being in power.”

Reeves, the Smith College professor, said Kiir is honest but has been “overwhelmed by the tasks of the presidency in a new country that has seen no development efforts for decades.”

Kiir, Reeves added, may resent Machar’s formal education and “political glibness.”

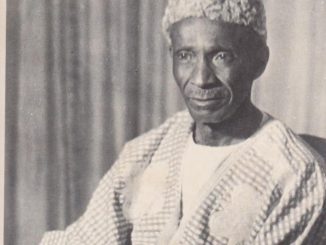

Machar, 61, was a college student at the end of Sudan’s first civil war, one of a small number of South Sudanese allowed to attend the University of Khartoum. He studied engineering, and continued his education in Scotland and later in Britain, earning a doctorate in strategic planning in 1984.

It was then that he joined the SPLM and SPLA, entering at a high rank because of his education.

Machar’s marriage to British aid worker Emma McCune, and their life in war-ravaged southern Sudan, became the subject of a book titled “Emma’s War.” In 1993, at the age of 28, McCune was killed in a car crash.

Machar had split from Garang and Kiir in 1991, creating a breakaway faction of the SPLM that drew support from some ethnic Nuer groups. Later that year, he was blamed for a massacre in Bor, where Nuer soldiers loyal to him killed hundreds of ethnic Dinka. Over the next several years, Machar collaborated with the Khartoum government, who viewed him as a useful tool to weaken Garang, Kiir and the SPLM. He signed a peace accord in 1997, alienating him from Kiir and the rest of the SPLM leadership.

“None of this is forgotten — by anyone,” Reeves said.

In 2002, Machar switched sides again, formally mending fences with Garang and rejoining the SPLM. When Garang died, Kiir anointed Machar vice president, largely to appease ethnic Nuers, Reeves said.

Machar’s open criticism of Kiir grew louder in the first half of 2013, resulting in his ouster this past summer. Two weeks ago, Machar and others purged by Kiir released a statement accusing him of “dictatorial tendencies” and of leading the SPLM and the country toward “the abyss.”

“He has always been overly ambitious and willing to see lives lost as he takes great risks on his own behalf,” Reeves said of Machar. “In that sense, what we are seeing now is entirely in character. We don’t need to ask whether it was a coup. It clearly is an attempted coup now. “

Leave a Reply